The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Great Cattle Trail, by Edward S. Ellis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Great Cattle Trail Author: Edward S. Ellis Release Date: October 8, 2009 [EBook #30212] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GREAT CATTLE TRAIL *** Produced by David Edwards, Darleen Dove and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

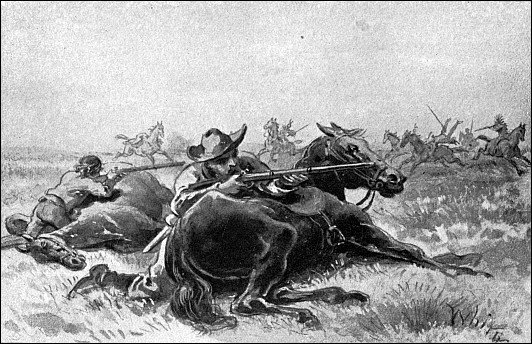

A Race for Life.

FOREST AND PRAIRIE SERIES––No. 1

THE GREAT CATTLE TRAIL

BY

EDWARD S. ELLIS

AUTHOR OF THE “WYOMING SERIES,” “LOG CABIN SERIES,”

“DEERFOOT SERIES,” ETC.

THE JOHN C. WINSTON CO.,

PHILADELPHIA,

CHICAGO, TORONTO.

Copyright, 1894,

BY

PORTER & COATES.

CHAPTER |

PAGE |

|

| I. | At the Ranch. | 1 |

| II. | An Alarming Interruption. | 10 |

| III. | Just in Time. | 19 |

| IV. | A Desperate Venture. | 28 |

| V. | Upstairs and Downstairs. | 36 |

| VI. | Dinah’s Discovery. | 44 |

| VII. | Dinah’s Exploit. | 52 |

| VIII. | In the Mesquite Bush. | 61 |

| IX. | At Fault. | 69 |

| X. | A Surprise. | 77 |

| XI. | Changing Places. | 85 |

| XII. | On the Roof. | 94 |

| XIII. | A Dead Race. | 102 |

| XIV. | The Friend in Need. | 111 |

| XV. | Vanished. | 119 |

| XVI. | Cleverly Done. | 127 |

| XVII. | At Fault. | 135 |

| XVIII. | An Unexpected Query. | 143 |

| XIX. | Down the Ladder. | 151 |

| XX. | “The Boys Have Arrived!” | 159 |

| XXI. | Through the Bush. | 167 |

| XXII. | Thunderbolt. | 180 |

| XXIII. | “Good-by!” | 191 |

| XXIV. | A Strange Delay. | 203 |

| XXV. | Heading Northward. | 216 |

| XXVI. | A Shot from the Darkness. | 228 |

| XXVII. | Shackaye, the Comanche. | 238 |

| XXVIII. | A Mishap. | 247 |

| XXIX. | Old Acquaintances. | 258 |

| XXX. | At Bay. | 264 |

| XXXI. | The Flag of Truce. | 276 |

| XXXII. | Diplomacy. | 288 |

| XXXIII. | Driven to the Wall. | 295 |

| XXXIV. | The Flank Movement. | 301 |

PAGE |

|

| A Race for Life. | Frontispiece |

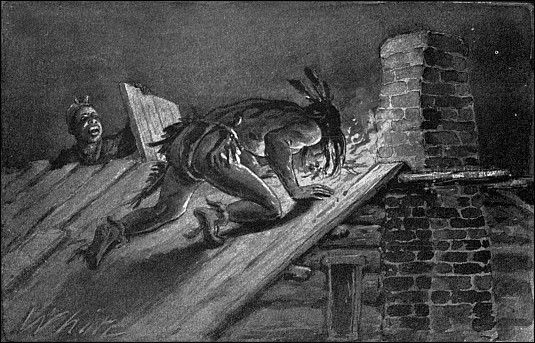

| A Startling Discovery. | 52 |

| The Last Stand. | 264 |

Avon Burnet, at the age of eighteen, was one of the finest horsemen that ever scurried over the plains of Western Texas, on his matchless mustang Thunderbolt.

He was a native of the Lone Star State, where, until he was thirteen years old, he attended the common school, held in a log cabin within three miles of his home, after which he went to live with his uncle, Captain Dohm Shirril, with whom the orphan son of his sister had been a favorite from infancy.

Avon was bright, alert, unusually active, and exceedingly fond of horses from the time he was able to walk. His uncle had served through the Civil War in the Confederate 2 army, returning to Texas at the close of hostilities, thoroughly “reconstructed,” and only anxious to recover his fortunes, which had been scattered to the four winds of heaven during the long, bitter struggle.

The captain had no children of his own, and it was natural, therefore, that he and his wife should feel the strongest attachment for the boy who was placed in their care, and who, should his life be spared, would inherit whatever his new parents might be able to leave behind them when called to depart.

Avon had reached the age named, when to his delight he was told that he was to accompany the large herd of cattle which was to be driven northward, through upper Texas, the Indian Nation, and Kansas over the Great Cattle Trail, along which hundreds of thousands of hoofs have tramped during the years preceding and following the War for the Union.

Young as was our hero, he had served his apprenticeship at the cattle business, and was an expert at the round-up, in branding, in cutting 3 out, in herding, and all the arduous requirements of a cowboy’s life. It was understood, therefore, that he was to be rated as a full hand among the eight men who, under his uncle, were to have charge of two thousand cattle about to start on the long tramp northward.

“It’s the hardest kind of work,” said the captain to his nephew, as the two sat in the low, flat structure where the veteran made his home, with his wife and one colored servant, “but I haven’t any fear that you will not pull through all right.”

“If I am not able to do so now, I never shall be,” replied Avon, with a smile, as he sat on the rough, home-made stool, slowly whittling a piece of wood, while his aunt, looking up from her sewing, remarked in her quiet way:

“It will be lonesome without Avon.”

“But not so bad as when uncle was off to the war,” ventured the youth, gazing affectionately at the lady.

The captain was sitting with his legs crossed, slowly smoking the old briarwood which he had carried through many a fierce 4 campaign, and seemingly sunk in deep thought. Like his nephew, he was clad in the strong serviceable costume of the Texan cowboy, his broad sombrero resting with a number of blankets on pegs in the wall.

It was evening, with a cold, piercing wind almost like one of the cutting northers blowing around the homely structure. The herd were gathered at a point about five miles to the northward, whence the real start was to be made at an early hour on the morrow. This arrangement permitted the captain and his young friend to spend their last night at home.

“No,” replied Mrs. Shirril, referring to the last remark of her nephew, “there never can be any worse days than those, when I did not know whether your uncle had not been dead for weeks or possibly months.”

“You must have had pretty tough times, aunt.”

“Well, they might have been improved, but Dinah and I managed to get along a great deal better than some of our neighbors. Here in Texas we were so far from the war 5 that I may say I never heard a hostile shot fired, except by the Indians who came down this way now and then.”

“They were the same, I suppose, that still trouble us.”

“I believe so, mostly Comanches and sometimes Kioways, with perhaps others that we didn’t know. They did much to prevent our life from becoming dull,” added the brave little lady, with another smile.

“The women in those days had to know how to shoot the rifle, ride horses, and do the work of the absent men.”

“I don’t know how we could have got along if we hadn’t learned all those things. For years I never knew the taste of coffee, and only rarely was able to obtain a pinch of coarse brown sugar; but we did not suffer for meat, and, with the help of Dinah, we could get a few things out of the earth, so that, on the whole, I think I had much easier times than my husband.”

“I am not so sure of that,” remarked Captain Shirril, rousing himself; “we had rough days and nights, beyond all doubt, but after 6 all, there was something about it which had its charm. There was an excitement in battle, a thrill in the desperate ride when on a scout, a glory in victory, and even a grim satisfaction in defeat, caused by the belief that we were not conquered, or that, if we were driven back, it was by Americans, and not by foreigners.”

“That’s an odd way of putting it,” remarked the wife, “but was it not the high health, which you all felt because of your rough outdoor life? You know when a person is strong and rugged, he can stand almost anything, and find comfort in that which at any other time brings only wretchedness and suffering.”

“I suppose that had a good deal to do with it, and that, too, may have had much to do with sustaining you and Dinah in your loneliness.”

The captain raised his eyes and looked at two old-fashioned muzzle-loading rifles, suspended on a couple of deer’s antlers over the fireplace, and smiling through his shaggy whiskers, said:

“You found them handy in those days, Edna?”

“We never could have got along without them. They served to bring down a maverick, or one of our own cattle, when we were nearly starving, and sometimes they helped drive off the Indians.”

Captain Shirril shifted his position, as though uneasy over something. His wife, who was familiar with all his moods, looked inquiringly at him.

“What troubles you, Dohm?”

“If I hadn’t promised Avon that he should go with me northward, I would make him stay at home.”

Wife and nephew stared wonderingly at him.

“The Comanches have been edging down this way for more than a week past; I believe they mean to make trouble.”

It would be supposed that such an announcement as this caused dismay, but it did not. Even Dinah, who was busy about her household duties, and who heard the remark, paused only a moment to turn up her nose and say scornfully:

“If dey’ve done forgot how we allers sarve de likes ob dem, jes’ let ’em try it agin. Dat’s all.”

She was a tall, muscular negress, whom an ordinary man might hesitate to make angry. She passed to another part of the room, after muttering the words, and seemed to feel no further interest in a subject which ought to have made her blood tingle with excitement.

“If the Comanches are hovering anywhere in the neighborhood,” said Mrs. Shirril in her gentle way, “it is in the hope of running off some of the cattle; you have them all herded and under such careful care that this cannot be done. When the Indians find you have started northward with them, they will follow or go westward to their hunting grounds; surely they will not stay here.”

“I wish I could believe as you do.”

“And why can’t you, husband?”

“Because Indian nature is what it is; you understand that as well as I. Finding that they cannot steal any of our cattle, they will try to revenge themselves by 9 burning my home and slaying my wife and servant.”

“But they have tried that before.”

“True, but their failures are no ground to believe they will fail again.”

“It is the best ground we can have for such belief.”

“If you think it best that I shall stay at home, I will do so,” said the young man, striving hard to repress the disappointment the words caused him.

“No; you shall not,” the wife hastened to interpose; “everything has been arranged for you to go with your uncle.”

“Was there ever a wife like you?” asked the captain admiringly; “there is more pluck in that little frame of yours, Edna, than in any one of my men. Very well; Avon will go with us, but I can tell you, I shall be uneasy until I get back again.”

“We have neighbors,” she continued, still busy with her sewing, “and if we need help, can get it.”

“I declare,” observed the captain grimly, “I forgot that; Jim Kelton’s cabin is only 11 eight miles to the south, and Dick Halpine’s is but ten miles to the east; if the redskins do molest you, you have only to slip in next door and get all the help you want.”

As we have said, it was a chilly night in early spring. The moon was hidden by clouds, so that one could see but a short distance on the open prairie. A fitful wind was blowing, adding to the discomfort of outdoors, and causing the interior of the cabin to be the more comfortable by contrast.

But a few rods to the westward was a growth of mesquite bush, in which the two mustangs that the captain and his nephew expected to ride were wandering at will. The animals were so trained that either would come at the whistle of his master, who, therefore, felt sure of finding him at command when wanted––that is, provided no outsiders disturbed him. This mesquite growth, consisting of open bushes which attain a height of eight or ten feet, extended over an area of several acres, affording the best kind of hiding-place for man or animal.

The signs of their old enemies, the Comanches, 12 to which Captain Shirril referred, had been noticed by his men, including young Avon Burnet. They had seen the smoke of camp-fires in the distance, had observed parties of horsemen galloping to and fro, and, in fact, had exchanged shots with the dusky marauders when they ventured too near in the darkness.

There could be no doubt that these fellows were on the watch for a chance to stampede the cattle, but the vigilance of the cowboys prevented that disaster. Most of the latter believed the Comanches would hover on their flank, probably until the beasts were well out of Texas and far over the line in the Indian Nation or Kansas. That they would stay behind to avenge themselves upon the wife and servant of the captain was not to be believed. The wife was equally certain on that point, so their leader suffered himself to be persuaded that his misgivings were groundless.

But this feeling of security, which was felt by all, suffered a startling interruption.

When Captain Shirril erected his humble 13 cabin several years before, he did not forget the danger to which he was certain to be exposed from the Indians. The wooden walls were heavy and bullet-proof, and the door was capable of being barred so strongly at an instant’s warning, that nothing less than a battering ram could drive it inward. The windows were too narrow to admit the passage of the most elongated redskin that ever wormed himself into the camp of an enemy. The structure was long and low, with an upper story, in which the cowboys slept whenever it was advisable to do so.

“You have had so much experience with this kind of business,” said the captain, “that I suppose I ought not to feel uneasy, even if I knew you would be attacked, for there are two guns here ready for you and Dinah, and you have both proven that you understand how to use the weapons; there is plenty of ammunition, too, and since you have had full warning of what may possibly take place–––”

At that instant the resounding report of a rifle broke the stillness on the outside, 14 there was a jingle of glass, and the pipe which Captain Shirril had held in his mouth while talking was shattered as if from the explosion of a torpedo within the bowl.

Nothing could have shown the wonderful training of this little family in the perils of the frontier more strikingly than did their actions at this moment. Not a word was spoken, but almost at the instant the alarming occurrence took place, the captain, his wife, and his nephew leaped backward with lightning-like quickness. The movement took the three out of range of the two windows at the front of the house, with the door midway between, those being the only openings on the lower floor.

Dinah happened to be at the extreme rear, where she was safe for the time. She was about to advance, when checked by the crash of the window pane and the crack of the rifle.

“For de Lawd’s sake,” she exclaimed, “de warmints hab come!”

“So they have,” replied the captain, rising upright from his crouching posture, “and see what they have done!”

He held up the stem of his pipe, which he had kept between his teeth during the exciting moments, with such a grim expression of woe that, despite the frightful incident, his wife and even Avon smiled.

“It is a pity indeed,” she said, “you will have to use your new one, and I know how much that will pain you.”

“They shall pay for this,” he added with a shake of his head.

Fortunately the rifles of himself and nephew were leaning in the corner, where they could be readily seized without exposing themselves to another treacherous shot. The men laid hands on them at once.

The weapons were of the repeating kind, and among the best that money could buy in San Antonio.

The two guns belonging to Mrs. Shirril and their servant rested together on the deer’s prongs over the mantel, and, to reach them, one must expose himself to another shot from the outside.

Following the rifle report, the sound of horses’ hoofs were heard galloping rapidly 16 around the cabin. The captain listened intently for a moment, holding one hand aloft as a signal for the others to keep silent.

“There’s fully a dozen of them,” he said a minute later in a low voice.

“But they know you and Avon are here,” added his wife, who was standing motionless just behind him, without any evidence of excitement except that her face was a shade paler than usual.

“I should think so, judging from that,” he replied, spitting the stem of his pipe upon the floor; “but I must get those guns for you.”

“Don’t think of it,” she persisted, laying her hand on his shoulder; “you will surely be shot, and there’s no need of them yet.”

“You may as well begin at once; you haven’t had any practice for months.”

Gently removing the hand of his wife, whom he loved as he did his life, the captain, holding his own gun in hand, began moving stealthily across the floor toward the fireplace. Had he been on his feet, he must have been observed by anyone in the position of the 17 savage that had fired the shot which was so well-nigh fatal, but, while so close to the floor, he would not be seen by any Comanche unless he was quite close to the window.

The redskin might and might not be there: that risk must be taken, or the guns would have to be left alone for the time.

Mrs. Shirril was more disturbed than ever, for she knew as well as did her husband the risk he ran, but she knew, too, that, when he once decided to do a thing, it was idle to seek to restrain him.

The burning wood threw an illumination through the room which rendered any other light unnecessary, and the captain could not have been in clearer view had the midday sun been shining. Nevertheless he crept slowly forward, until in front of the fireplace. Then he paused to consider which of two methods he had in mind was the better for obtaining the weapons.

The Comanches were still circling back and forth on the outside, uttering their whoops and firing their guns at intervals, though the latter consisted of blind shooting, and was 18 meant to terrify the defenders, since none of the bullets found its way through either of the windows.

Captain Shirril took but a few seconds to decide upon his course of action.

Bending as closely to the floor of the cabin as he could, the Texan advanced until directly in front of the crackling fire, when he reached up with his Winchester, which was grasped near the muzzle. By this means he placed the stock directly beneath the two weapons resting on the deer antlers.

With a deftness that would hardly have been expected, he raised both guns until their stocks were lifted clear off their support, when he began gently lowering them, so as to bring them within his reach. He might have flirted them free by a single quick movement and let them fall upon the floor; but he wished to avoid this, since he ran the risk of injuring them.

None knew better than Avon Burnet the 20 great danger of this apparently simple act on the part of his uncle. The chances were so immeasurably in favor of his discovery that he was certain it would take place. While the wife and servant held their breath in a torture of suspense, the youth, with his cocked rifle firmly grasped, stole softly along the side of the cabin until close to the door. In reaching the spot, he stooped so as to move beyond the first opening, the proceeding placing him between the windows, with his left elbow against the heavy door.

In this situation his nerves were at the highest tension. Everything was in plain sight, but he was listening intently to the movements of his enemies. He heard the sounds of the mustangs’ hoofs, as they circled swiftly about the cabin, sometimes turning quickly upon themselves, and at varying distances from the structure. Now and then one or two of the horsemen would rein up abruptly, as if striving to peer through the openings, or about to apply for admission.

It may seem incredible, but there is no 21 reason to doubt the fact that, at the moment Captain Shirril began cautiously reaching upward with his weapon, the youth heard one of the Comanches slip down from the back of his mustang and approach the door. His hand moved softly over the rough surface, as though searching for the latch string, which was generally hanging out; and, finding it not, he began stealing to the window just beyond.

This was the very thing Avon dreaded above all others, for it was inevitable that he should detect the figure of the Texan operating so guardedly in front of the fire.

Such proved to be the fact. Whether the youth actually observed the action of the Indian, or whether he fancied he heard him moving along the side of the house, cannot be said with certainty; but a faint rustle in front of the shattered glass made known that the dusky miscreant was there, and had detected the stratagem of the Texan, who at that moment was in the act of lowering the gun from the deer’s prongs over the mantel.

His uncle was so clearly in his field of vision that, without looking at him, Avon did not miss the slightest movement, but his whole attention was fixed on the window, and it was well it was so.

“Look! look! Avon, do you see that?”

It was his aunt who uttered the terrified question with a gasp, as she pointed at the narrow opening.

The youth had observed the object which appalled the lady; the muzzle of a gun was slowly gliding through the window.

Captain Shirril had been discovered, and the Comanche was fixing his weapon in position to fire a fatal shot. He might have stood back a couple of paces and discharged it without revealing his presence, but a better aim could be secured by thrusting a few inches of the barrel into the room.

At the instant the dark muzzle showed itself and the gleam of the firelight was reflected from it, Avon leaned his own rifle against the door at his side, quickly drew his revolver from the holster at his hip, sprang forward like a cat, and seizing the 23 muzzle of the gun threw it upward toward the ceiling.

It was done in the nick of time, for the Comanche pressed the trigger just then, and the bullet which, had Avon’s action been delayed a single moment, would have killed Captain Shirril, was buried in the timbers overhead.

The daring act brought the youth directly in front of the window, where for the instant he was exposed to any shot from the outside.

As he made the leap he saw the face of the warrior, agleam with paint and distorted with passion, but slightly flustered by the unaccountable occurrence. Before he could recover, and at the same instant, Avon darted his revolver through the shattered window pane and let fly with two chambers in quick succession. An ear-splitting screech and a heavy fall left little doubt of the success of the daring act. The Comanche had not only been hit, but hit hard.

Although startled by the noise and flurry, Captain Shirril was too much of a veteran to 24 be taken at fault. His big right hand closed around the two weapons for which he had run all this risk, and partly straightening up, he bounded to the rear of the little room with three rifles secure in his grasp, and with not a hair of his head harmed.

Avon was as much on the alert as he, and reached the shelter at the same moment.

“It was confoundedly more risky than I supposed,” remarked the captain, with a smile and a shake of his head, “but all’s well that ends well; I guess you dropped him, my boy.”

“I shouldn’t wonder, for I couldn’t have had a better chance,” was the modest reply of the youth.

“It was one of the neatest things I ever saw, and I’m proud of you,” exclaimed his relative, slapping him affectionately on the shoulder. “I said you would count as a full hand on the trip to Kansas, but at this rate you’ll add up double.”

Avon blushed as he used to do in school, when his teacher praised him for excellent lessons, and made no answer, but the eyes of 25 his aunt kindled with love for the brave fellow who, by his readiness of resource, had saved her husband’s life. Even Dinah, with whom he had always been a favorite, added an expression of affection for the boy who had done so well.

There were now two men and two women within the Texan’s cabin, and each held a trusty weapon, while there was plenty of ammunition for all. It might well be asked, therefore, what cause they had for alarm.

Outside were a dozen or more savage Comanches, who are among the finest horsemen in the world, and who in fighting ability and bravery are surpassed by none, unless the Apaches of the Southwest.

It was a piece of daring on the part of these dusky raiders thus to attack the cabin, when they knew how well it was defended. Captain Shirril was probably right in supposing they believed that he and his nephew were with the rest of the cowboys, watching the herd five miles away. Finding the couple in the cabin, they could not resist the temptation to bring down the head of the household, 26 after which they must have supposed the rest would be an easy task.

But having failed, probably they would have withdrawn but for the shot of Avon Burnet, that had brought down one of their best warriors, and their well-known desire for revenge urged them to the most desperate measures against the whites.

But a few minutes’ whispered conference at the rear of the cabin brought to light the fact that every one of our friends, including even Dinah, understood that their peril was of the gravest nature conceivable.

The structure of the cabin was so thoroughly seasoned by its years of exposure that it would be an easy matter for their assailants to set fire to it, and that they would make the attempt was not to be doubted. They always prepared for such action, and none knew better than they its fearful effectiveness.

“We might reach the boys by means of the reports of our guns,” said the captain, “if the wind were not the wrong way, but they won’t catch the first sound, especially as they will 27 have their hands full in looking after the cattle.”

“But dey will obsarve de light ob de fiah,” suggested Dinah.

“Undoubtedly, but when they do see it,” said her master, “it will be too late to help us. They haven’t a suspicion of anything of this kind; if they had, they would be down here like so many cyclones.”

“There is one way of letting them know,” said Avon.

“What’s that?”

“By carrying word to them, and I’m going to try it!”

The family of Texans were not the ones to indulge in sentimentality or useless speculations when action was demanded. The first feeling of amazement following Avon’s announcement of his resolution quickly passed, but his uncle deemed it his duty to impress upon him the desperate nature of his scheme.

“I don’t see one chance in twenty of your succeeding,” said he.

“And if I stay what are the chances for us all?”

“Possibly one in a hundred.”

“Then I shall go,” he quietly replied, compressing his lips as his fine eyes kindled.

“There is hope, if you can reach the bush, but the rub will be to do that.”

“They grow close to the house, and the 29 Comanches will not be looking for any attempt of that kind.”

“Is it not best to wait until later?” asked Mrs. Shirril.

“No,” was the sensible response of her nephew; “the prospect of success will decrease with every passing minute. They will think, and with reason, that we have repelled their first attack so sharply that we are confident of beating them off altogether. After a time, when things begin to look bad for us, they will look for something of that nature, and be so well prepared for it that it will be hopeless.”

“He is right,” assented the captain. “I don’t ask you to try it, Avon, but, if you are determined to do so, now is the time.”

“My sentiments exactly, and I’m going.”

He dreaded anything in the nature of a scene, one reason for his moving so promptly being his desire to avert such a trial.

But now that the momentous step was decided upon, the all-important question remained as to the best means of making the start.

The whole interior of the lower story was so brightly illuminated by the blaze on the hearth that the moment the door was opened, even for only a few inches, it would show from the outside. Anxious as Avon was to be off, he knew better than to start under such conditions.

“The sooner that fire goes out, the better for all of us,” said the captain; “it is too tempting to the scamps.”

On the row of pegs near him hung several heavy blankets, such as are used by all plainsmen and cowboys. Those which the captain and his nephew meant to take on their journey northward were in camp five miles away.

Setting down his gun, he lifted one of the heavy pieces of cloth, whose texture, like the celebrated blankets of the Navajoe Indians, was almost close enough to be waterproof. He paused for a minute to adjust the folds, and then, forgetful of the danger he had run a short time before, he stepped hastily across the room, and stooping down flung the blanket over the blaze so as to enclose it entirely.

The effect was instantaneous. The room was wrapped in darkness as dense as that outside, though the consequences of the act promised to be anything but pleasant in the course of a few minutes.

“Now, Avon, is your time!” called the captain in an undertone.

“I’m off; good-by,” came from the gloom near the door, where the sounds showed that he was engaged in raising the ponderous bar from its sockets.

Captain Shirril stepped hurriedly to the spot, and found the door closed but unfastened. Even in his haste the youth did not forget to shut it behind him, leaving to his friends the duty of securing it in place.

“He is gone; God be with him!” he whispered to his wife and servant, who with painfully throbbing hearts had stepped to his side.

While speaking, he refastened the structure, and in less time than it has taken to tell it everything inside was as before, with the exception that where there had been four persons, there were now only three.

All forgot their own danger for the moment 32 in their anxiety for the youth, who had so eagerly risked his own life to save them from death.

Bending his head, the captain held his ear against the tiny opening through which the latchkey had been drawn earlier in the evening, when the heavy bar was put in place. The Texan was listening with all the intentness possible.

“It seems impossible that he should get away,” was his thought, “and yet the very boldness of his plan may give it success.”

The shot from within the cabin, followed so soon by the complete darkening of the interior, must have caused some confusion among the Comanches, for otherwise Avon would have been shot or captured the moment he stepped outside of the cabin.

For the space of two or three seconds Captain Shirril absolutely heard nothing, except the soft sighing of the night wind among the mesquite bushes near at hand. The stillness could not have been more profound had every living thing been moved to a distance of a hundred miles.

He had listened only a minute or two, however, when he heard a warrior run rapidly around the building, coming to an abrupt stop directly in front of the door. Thus he and the Texan stood within a few inches of each other, separated only by the heavy structure, which, for the time, barred all entrance.

Captain Shirril even fancied that the eye of the redskin was pressed against the opening, in the vain effort to gain sight of the interior. Had the Comanche chosen to place his lips there, how readily he could have whispered into the ear of his enemy!

That the Texan was right in suspecting one of the warriors was so very near was proven a moment later, when a second Indian approached with his mustang on the walk, dropped lightly to the ground, and coming forward, halted so close to the door that he almost touched it.

The captain knew this because he heard the two talking in low tones. He understood the tongue of the dusky miscreants, but though he listened closely, could not catch the meaning of a word that passed between them. 34 Their sentences were of the short, jerky character common to all American Indians, accompanied by a peculiar grunting, which helped to obscure their meaning.

The unspeakable relief of the listener was caused by the awakening of hope for his nephew. He was certainly some way from the cabin, for had he stayed near the door, discovery was inevitable by the two warriors now standing there. Indeed, they must almost have stumbled over him.

But he might be still within a few paces, unable to stir through fear of detection. Extended flat on the ground, on the alert for the first possible opening, he was liable to discovery at every moment.

In fact, so far as Avon was concerned, he had crossed the Rubicon; for, if seen, it was impossible to re-enter the cabin, the door of which had been shut and barred.

The warriors who had paused in front of Captain Shirril kept their places but a brief while, when they moved off so silently that he could not tell the direction they took. Everything remained still for several minutes, when 35 the listener once more fancied he heard something unusual.

It was a stir among the mesquite bushes, such as might be caused by a puff or eddy in the wind, which blew quite steadily, though with moderate force.

He was listening with all his senses strung to the highest point, when the stillness was broken by the report of a rifle, accompanied by a ringing shriek, both coming from a point within a few rods of the cabin. The hearts of the inmates stood still, the wife alone finding voice to exclaim in horrified tones:

“Poor Avon! he has fallen! he has given his life for us!”

Profound stillness followed the despairing exclamation of Mrs. Shirril, who believed that her nephew had gone to his death while trying to steal away from the cabin in which his friends were held at bay by the Comanches.

The quiet on the outside was as deep and oppressive as within. There was the sharp, resounding report of the rifle, followed on the instant by the wild cry of mortal pain, and then all became like the tomb itself.

It was singular that the first spark of hope was kindled by the words of the colored servant, Dinah.

“What makes you tink de boy am dead?” she asked, a moment after the woful words of her mistress.

“Didn’t you hear him cry out just now?”

“No; I didn’t hear him nor did you either; dat warn’t de voice ob Avon.”

“How can you know that?” asked Mrs. Shirril, beginning to feel anew hope within her.

“Lor’ o’ massy! habent I heerd de voice ob dat younker offen ’nough to know it ’mong ten fousand? Habent I heerd him yell, too? he neber does it in dat style; dat war an Injin, and de reason dat he screeched out in dat onmarciful way war ’cause he got in de path ob Avon and de boy plugged him.”

“By gracious, Dinah! I believe you’re right!” was the exclamation of Captain Shirril, so joyous over the rebound from despair that he was ready to dance a breakdown in the middle of the floor.

“Course I is right, ’cause I allers is right.”

“I suppose there is some reason in that, but please keep quiet––both of you, for a few minutes, while I listen further.”

The women were standing near the captain, who once more inclined his head, with his ear at the small orifice in the door.

The seconds seemed minutes in length, but as they wore away, nothing definite was heard. Once or twice the tramp of horses’ feet was noticed, and other sounds left no doubt that most of the Comanches were still near the dwelling.

This listening would have lasted longer, but for an unpleasant though not dangerous interruption. Dinah, who seemed to be meeting with some trouble in her respiration, suddenly emitted a sneeze of such prodigious force that her friends were startled.

It was not necessary for them to enquire as to the cause. The blanket that had been thrown upon the flames, and which brought instant night, did its work well, but it was beginning to suffer therefrom. The fire was almost smothered, but enough air reached it around the edges of the thick cloth to cause it to burn with considerable vigor, and give out a slight illumination, but, worst of all, it filled the room with dense, overpowering smoke. Breathing was difficult and the odor dreadful.

“This will never do,” said the captain, 39 glancing at the fireplace, where the glowing edges of the blanket were growing fast; “we won’t be able to breathe.”

His first thought was to fling another blanket upon the embers, thereby extinguishing them altogether, but his wife anticipated him by scattering the contents of the water pail with such judgment over the young conflagration that it was extinguished utterly. Darkness reigned again, but the vapor, increased by the dousing of the liquid, rendered the room almost unbearable.

“You and Dinah had better go upstairs,” said the captain to his wife; “close the door after you, and, by and by, the lower floor will clear; I can get enough fresh air at the little opening in the door and by the windows to answer for me; if there is any need of you, I can call, but perhaps you may find something to do up there yourselves.”

The wife and servant obeyed, each taking her gun with her, together with enough ammunition to provide for fully a score of shots.

The cabin which Captain Dohm Shirril had erected on his ranch in upper Texas was long 40 and low, as we have already intimated. There was but the single apartment on the first floor, which served as a kitchen, dining and sitting room, and parlor. When crowded his guests, to the number of a dozen, more or less, could spread their blankets on the floor, and sleep the sleep that waits on rugged health and bounding spirits.

The upper story was divided into three apartments. The one at the end served for the bedroom of the captain and his wife; the next belonged to Dinah, while the one beyond, as large as the other two, was appropriated by Avon and such of the cattlemen as found it convenient to sleep under a roof, which is often less desirable to the Texan than the canopy of heaven.

Few of these dwellings are provided with cellars, and there was nothing of the kind attached to the residence of Captain Shirril. The house was made of logs and heavy timbers, the slightly sloping roof being of heavy roughly hewn planking. Stone was scarce in that section, but enough had been gathered to form a serviceable fireplace, the 41 wooden flue of which ascended to the roof from within the building.

This brief description will give the reader an idea of the character of the structure, in which one man and two women found themselves besieged by a war party of fierce Comanches.

The ceiling of the lower floor was so low that, had the captain stood erect with an ordinary silk hat on his head, it would have touched it. The stairs consisted of a short, sloping ladder, over which a trap-door could be shut, so as to prevent anyone entering from below.

Inasmuch as smoke generally climbs upward, the second story would have proven a poor refuge had the women waited any time before resorting to it. As it was, considerable vapor accompanied them up the rounds of the ladder, but, when the trap-door was closed after them, the greater purity of the air afforded both relief.

It will be recalled that the lower story was furnished with two windows at the front, of such strait form that no man could force his 42 way through them. The upper floor was more liberally provided in this respect, each apartment having a window at the front and rear, though the foresight of Captain Shirril made these as narrow as those below. Indeed they were so near the ground that otherwise they would have formed a continual invitation to hostile parties to enter through them.

So long as an attacking force kept off, three defenders like those now within the house might defy double the number of assailants that threatened them. No implement of warfare at the command of the red men was sufficient to batter down the walls, or drive the massive door from its hinges.

But the real source of danger has been indicated. The cabin was located so far toward Western Texas, that it was exposed to raids from the Comanches and Kioways, while occasionally a band of Apaches penetrated the section from their regular hunting grounds in Arizona or New Mexico.

Although the red men might find it impossible to force an entrance, yet the darkness allowed them to manœuvre outside, and lay 43 their plans with little danger of molestation. The roof of the building had been seasoned by its long exposure to the weather, until it was as dry as tinder. This was increased, if possible, by the drought that had now lasted for months in that portion of Texas. A slight fire would speedily fan itself into a flame that would reduce the building to ashes.

“And it only needs to be started,” thought Captain Shirril, when he found himself alone below stairs, “and it will do the work; it was very thoughtful in Edna to dash that pailful of water on the smouldering blanket, and it quenched the embers, but, all the same, it required the last drop in the house.”

However, there was nothing to be feared in the nature of thirst. The defenders could go without drink easily enough for twenty-four hours, and the issue of this serious matter would be settled one way or other long before that period passed. The cowboys would not wait long after sunrise for their leader, before setting out to learn the cause of his delay.

The question of life and death must be answered before the rising of the morrow’s sun.

When Captain Shirril told his wife that she and the servant were likely to find something to engage their attention above stairs, he spoke more in jest than earnest, but the remark served to prove the adage that many a truth is spoken at such times.

Of course, the upper part of the house was in as deep gloom as the lower portion, and the women took good care in passing the windows lest some stray shot should reach them. They needed no light, for every inch of space had long been familiar.

Mrs. Shirril walked quietly through the larger apartment, without coming upon anything to attract notice, after which she went to her own room, Dinah accompanying her all the way.

“I don’t see that there is any need of our 45 remaining here,” said the mistress, “for there is no possible way of any of the Indians effecting an entrance.”

“’Ceptin’ frough de trap-door,” ventured the servant.

“That is over your room, but the scuttle is fastened as securely as the one below stairs.”

“Dunno ’bout dat; I’s gwine to see,” was the sturdy response of Dinah, as she walked rather heavily into her own boudoir; “any man dat comes foolin’ ’round dar is gwine to get hisself in trouble.”

Knowing precisely where the opening was located (an unusual feature of the houses in that section), she stopped directly under it, and reached upward with one of her powerful hands. The roof was still nearer the floor than was the latter to the floor below, so that it was easy for her to place her fingers against the iron hook which held it in place.

Of course she found the scuttle just as it had been for many a day; and Mrs. Shirril was right in saying it was as firmly secured as the ponderous door beneath them, for the 46 impossibility of getting a purchase from the roof, made only a slight resistance necessary from beneath. A dozen bolts and bars could not have rendered it stronger.

“It ’pears to be all right,” mused Dinah, “but folks can’t be too keerful at sich times––sh! what dat?”

Her ears, which were as keen as those of her friends, heard a suspicious noise overhead. It was faint, but unmistakable. The startling truth could not be doubted: one of the Comanches, if not more, was on the roof!

“If dat isn’t shameful,” she muttered, failing to apprise her mistress of the alarming discovery; “I wander what he can be after up dar––de Lor’ a massy!”

The last shock was caused by a scratching which showed that the intruder was trying to lift up the scuttle.

Evidently the Indians had made themselves as familiar with Captain Shirril’s domicile as they could without entering it. They had noticed the scuttle, and the possibility that it might be unfastened led one of them to climb undetected to the roof to make sure about it.

“Dat onmannerly warmint knows dat dat door am right over my room,” muttered the indignant Dinah; “and instead ob comin’ in by de reg’lar way, as a gemman orter do, he’s gwine to try to steal in frough de roof. When I get done wid him,” she added, with rising wrath, “he’ll know better nor dat.”

Still Mrs. Shirril kept her place in her own apartment, where she was striving so hard to learn something, by peering through and listening at one of her windows, that she noticed nothing else, though, as yet, the noise was so slight that it would have escaped the ears of Dinah herself, had she not been quite near it.

The colored woman groped around in the dark until her hand rested upon the only chair in the apartment. This she noiselessly placed under the scuttle, and stepped upon it with the same extreme care.

Her position was now such that had the door been open and she standing upright, her head, shoulders, and a part of her waist would have been above the roof. She had leaned her gun against the side of the chair, 48 so that, if needed, it was within quick reach. Then she assumed a stooping posture, with her head gently touching the underside of the door, and, steadying herself by grasping the iron hook, she stood motionless and listening.

“Yes, he’s dar!” was her instant conclusion, “and de wiper is tryin’ to onfasten de skylight ob my obpartment.”

Dinah’s many years spent in this wild region had given her a knowledge that she could not have gained otherwise. She knew that so long as the Comanche contented himself with trying to open the scuttle, nothing was to be feared; but, baffled in that, he was not likely to drop to the ground again without attempting more serious mischief, and that serious mischief could take only the single dreaded form of setting fire to the building.

It seems almost beyond belief, but it is a fact that this colored woman determined on defeating the purpose of the redskin, by the most audacious means at the command of anyone. She resolved to climb out on the roof and assail the Comanche.

Since she knew her mistress would peremptorily forbid anything of the kind, she cunningly took all the means at her command to prevent her plan becoming known to Mrs. Shirril, until it should be too late for her to interfere.

Stepping gently down to the floor, she moved the few steps necessary to reach the door opening into the other room, and which had not been closed.

“Is you dar, Mrs. Shirril?” she asked in a whisper.

“Yes, Dinah,” came the guarded response; “don’t bother me for a few minutes; I want to watch and listen.”

“All right; dat suits me,” muttered the servant with a chuckle, as she closed the door with the utmost care.

Everything seemed to favor the astounding purpose of the brave African, who again stepped upon the chair, though in her first confusion she narrowly missed overturning it, and brought her head against the scuttle.

She was disappointed at first, because she heard nothing, but a moment’s listening told 50 her that her visitor was still on deck, or rather on the roof. The fact that, after finding he could not effect an entrance, he still stayed, made it look as if he was meditating mischief of the very nature so much feared.

In accordance with her daring scheme, Dinah now softly slipped the hook from its fastening, holding it between her fingers for a moment before doing anything more. Had the Comanche known how matters stood, a quick upward flirt on his part, even though the hold was slight, would have flung the door flat on the roof and opened the way to the interior of the Texan’s cabin.

But not knowing nor suspecting anything of the kind, he did not make the attempt.

With no more tremor of the nerve than she would have felt in trying to kill a fly, Dinah softly pushed up the door for an inch at its outermost edge. This gave her a view of the roof on the side in front, with a shortened survey of the portion still nearer.

Her eyes were keen, but they detected nothing of the Comanche who was prowling about the scuttle only a few moments before. 51 The darkness was not dense enough to prevent her seeing to the edge of the roof on all sides, had her view been unobstructed. Could she have dared to throw back the door, and raise her head above the peak of the roof, she could have traced the outlines of the eaves in every direction.

But she was too wise to try anything like that. The slightest noise on her part would be heard by the Indian, who, like all members of the American race, had his senses trained to a fineness that seems marvellous to the Caucasian. He would take the alarm on the instant, and leap to the ground, or, what was more likely, assail her with his knife, since his rifle had been left below.

“What’s become ob dat villain?” Dinah asked herself, after peering about in the gloom for a full minute; “I wonder wheder he hasn’t got ’shamed ob hisself, and hab slunk off and is gwine down to knock at my door and ax my pardon––Lor’ a massy!”

There was good cause for this alarm on her part, for at that moment she made a discovery that fairly took away her breath.

The revelation that broke upon the senses of the colored servant did not reach her through her power of vision. She still saw nothing but the all-encircling night, nor did she hear anything except the sighing of the wind through the mesquite bush, or the guarded movements of the red men below.

It was her power of smell that told her an appalling fact. She detected the odor of burning wood!

The Indian whom she had heard prowling like a hungry wolf over the roof, was there for a more sinister purpose, if possible, than that of gaining entrance through the scuttle into the building. He had managed to climb undetected to his perch for the purpose of setting fire to the building, and not only that, but he had succeeded in his design.

A Startling Discovery.

The same delicacy of scent that had told the woman the frightful truth enabled her to locate the direction of the fire. It was over the peak of the roof, a little in front and to the left.

Gazing toward the point, she observed a dim glow in the darkness, such as might have been made by the reflection of a lucifer match. It was the illumination produced by the twist of flame the Comanche had kindled. If allowed to burn for a few minutes, the wind would fan it into an inextinguishable blaze.

How she managed to do what she did without discovery she never could have explained herself. But, holding the lid firmly grasped with one hand, she lifted it up until it stood perpendicular on its noiseless hinges.

As the door moved over to this position, her head and shoulders rose through the opening. Had her movements been quick, instead of deliberate, they would have suggested the action of the familiar Jack-in-the-box.

This straightening of her stature brought 54 her head several inches above the peak or highest portion of the house, and, consequently, gave her a view of the entire roof.

And looking in the direction whence the odor came, and where she had caught the tiny illumination, the brave colored woman saw a sight indeed.

A brawny Indian warrior was stooped over and nursing a small flame with the utmost care. How he had managed the difficult business thus far without detection from below, was almost beyond explanation.

But it followed, from what has been told, that he had climbed upon the roof, taking with him some twigs and bits of wood, without having been heard by Captain Shirril, who was listening intently at the lower door, and who heard more than one other noise that must have been slighter than that overhead.

It was probable that the warrior, having made his preparations, rode his horse close to the further corner of the cabin, where he stopped the animal, and rose to the upright position on his back. The roof was so low 55 that it could be easily reached in this way, and he was so far removed from the inmates that his action escaped notice, his presence being finally discovered in the manner described.

Finding he could not open the scuttle, he had crept over the peak of the roof, stooped down, and, gathering his combustibles with care, set fire to them. In doing this, he must have used the common lucifer match of civilization, since no other means would have answered, and the American Indian of the border is as quick to appropriate the conveniences as he is to adopt the vices of the white man.

Be that as it may, he had succeeded in starting the tiny fire, and, at the moment the wrathful Dinah caught sight of him, was placing several larger sticks upon the growing flame, and, bending over, was striving to help the natural wind by blowing upon the blaze.

The picture was a striking one. The glow of the flame showed the countenance of the Comanche plainly. His features were repellent, 56 the nose being Roman in form, while the cheek-bones were protuberant and the chin retreating. His long black hair dangled about his shoulders, and was parted, as is the custom among his people, in the middle. The face was rendered more repulsive by the stripes and splashes of yellow, white, and red paint, which not only covered it from the top of the forehead to the neck, but was mixed in the coarse hair, a portion of whose ends rested on the roof, as well as over his back.

As he blew, his cheeks expanded, his thin lips took the form of the letter O, fringed with radiating wrinkles around the edges, and the black eyes seemed to glow with a light like that of the fire itself, so great was his earnestness in his work.

No country boy accustomed to get up on cold mornings and build the family fires could have done his work better. He saw that while the sticks which were burning, and which he continued to feed and fan, were rapidly consuming and growing, they were eating into the dry roof on which they rested. They had already burned a considerable 57 cavity, which gleamed like a living coal, and it would not take long before a hold would be secured that would throw the whole structure into a blaze.

Dinah stood for several seconds gazing on the picture, as though she doubted the evidence of her own eyes. It seemed impossible that such a cruel plot should have progressed thus far without being thwarted. But the next moment her chest heaved with indignation, as she reflected that the red man stretched out before her was the very one that had tried to enter her apartment, and being frustrated by her watchfulness in that design, he was now endeavoring to burn them all to death.

The fact that the Comanche never dreamed of interruption caused him to withdraw his attention from everything except the business before him, and he continued blowing and feeding the growing flames with all the care and skill at his command. His wicked heart was swelling with exultation when––

Suddenly an object descended upon the flames like the scuttle-door itself, which 58 might be supposed to have been wrenched from its hinges and slammed down on the fire, quenching it as utterly and completely as if it were submerged in a mountain torrent.

That was the foot of Dinah.

Next, as the dumfounded warrior attempted to leap to his feet, something fastened itself like the claw of a panther in his long hair, with a grip that not only could not be shaken off, but which threatened to create a general loosening at the roots.

That was the left hand of Dinah.

At the same moment, when the dazed Comanche had half risen and was striving to get the hang of things, a vice closed immovably about his left ankle, and his moccasin was raised almost as high as his shoulder.

The agency in this business was the right hand of Dinah; and instantly she got in her work with the vigor of a hurricane. She possessed unusual power and activity, though it must not be supposed that the Comanche would not have given a good account of himself had he but possessed a second’s warning of what was coming. He had a knife at his 59 girdle, though his rifle, as has been said, was left behind with his companions, since his business did not make it likely that he would need anything of the kind, and it was an inconvenience to keep it by him.

“You onmannerly willian! I’ll teach you how to try to sneak frough de roof into my room!” muttered Dinah, who was now thoroughly aroused, “yer orter have your neck wringed off and I’ll do it!”

The Comanche was at vast disadvantage in being seized with such a fierce grip by the hair, which kept his face turned away from his assailant, while the vicelike grasp of his ankle compelled him to hop about on one foot, in a style that was as awkward as it was undignified. He realized, too, that despite all he could do to prevent it, his foe was forcing him remorselessly toward the edge of the roof.

But the warrior was sinewy and strong. He had been engaged in many a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, though never in anything resembling this. Finding the grip on his hair and ankle could not be shaken 60 off, he snatched out his keen-pointed knife with the intention of striking one of his vicious back-handed blows, which had proved fatal more than once, but just then the eaves were reached and over he went!

We must not forget our young friend, Avon Burnet, who volunteered so willingly to run every risk for the sake of helping his relatives out of the most imminent peril of their lives.

At the moment he saw Captain Shirril start forward to smother the fire, by throwing one of his heavy blankets over it, he lifted the heavy bolt from its place, and leaned it against the wall at the side of the door. Having decided on the step, he was wise in not permitting a minute’s unnecessary delay.

He stepped outside in the manner hinted, drawing the door gently to after him. He did not do this until he saw that the interior was veiled in impenetrable gloom.

He felt that everything now depended 62 upon his being prompt, unfaltering, and yet not rash. It may be said that the whole problem was to learn the right step to take, and then to take it, not an instant too soon nor too late. That, however, sums up the task of life itself, and the knowledge was no more attainable in one instance than in the other.

Finding himself in the outer air, Avon stood a few seconds, striving, as may be said, to get his bearings. He heard the trampling of horses’ hoofs, several guarded signals passing between the Indians, and was quite sure he saw the shadowy outlines of a warrior moving within a few paces of him.

While all this was not calculated to add to his comfort of body and mind, it was pleasing to the extent that it proved his presence on the outside was as yet neither known nor suspected. As my friend Coomer would say, he was standing “With the World Before Him.”

But he dare not think he was so much as on the edge of safety until he reached the mesquite bush, whose location he knew so 63 well, and whose dark outlines were dimly discernible in front, and at the distance of only a few rods.

The youth was thinking rapidly and hard. It seemed to him that the Comanches would naturally keep the closest watch of the front of the cabin, and, therefore, he was less liable to discovery if he made a dash from another point.

This conclusion was confirmed by the sudden taking shape of not only the figure of a horseman, but of a warrior on foot, who approached at right angles, the two halting in such a manner just before him that he know it was but momentary, and that they would come still nearer in a very brief while.

So long as he stood erect, with his back against the side of the dwelling, he was invisible to anyone who was not almost upon him. Retaining this posture, and with the rear of his clothing brushing against the building, he glided softly to the right until he reached the corner.

At the moment he arrived there, he saw that the horseman had slipped from his mustang, and he and the other warrior approached 64 close to the door, where, as it will be remembered, Captain Shirril heard them talking together in low tones.

This was altogether too near for comfort, and Avon, with the same noiseless movement, slipped beyond the corner of the house.

As he did so, he felt for an instant that all was over. An Indian brushed so near that the youth could have touched him by extending his hand.

How he escaped discovery was more than he could understand. It must have been that the warrior’s attention was so fixed upon the two figures at the front of the house that he did not glance to the right or left. Even such an explanation hardly makes clear the oversight on the part of one belonging to a race proverbial for its alertness and keen vision.

Before the young man recovered from his shock, he was astounded by another occurrence a hundred-fold more inexplicable. The profound stillness was suddenly broken by the ringing report of a rifle on the other side of the building, accompanied by the wild cry which caused the listening Captain Shirril and 65 his wife to believe it meant the death of their devoted nephew.

While the captain committed a grave mistake, for which he was excusable, Avon was equally at fault, and with as good if not a better reason. Not dreaming it possible that he could have a friend near the cabin and on the outside, he supposed the shot was fired by the captain to create a diversion in his favor.

While such, as the reader knows, was not the case, yet it served that commendable purpose.

The death-shriek of the stricken Comanche was still in the air, when, assuming a crouching posture, the youth made a dash for cover. He expected every moment that other rifles would be fired and he would be headed off. He could hardly understand it, therefore, when he felt the bushes strike his face, and he knew that he was among the mesquite, without suffering harm.

He would have continued his flight, had not the sounds in front shown that while he had been wonderfully fortunate up to this point, he had run almost into a group of his enemies.

The dense shadows of the bushes prevented him from seeing them, else they assuredly would have observed him, but, determined to go forward now at all hazards, and eager to seize the flimsiest thread of hope, he sank down on his hands and knees, anxious to continue his flight, but waiting to learn in what direction it should be made, if indeed it could be made at all.

There was one hope which he felt he must give up. The possibility of finding Thunderbolt, and using the matchless steed in his flight to the camp of the cowboys, had occurred to him more than once, though it would seem that it was altogether too much to look for any such good fortune as that.

“If I can only get clear of the parties, who seem to be everywhere,” was his thought, “I will run all the way to camp and bring the boys back in a twinkling.”

He could have drawn Thunderbolt to him by a single emission of the well-known signal, but such an attempt would have been the before the mustang, even if he was not 67 already in their possession, and the act would secure the capture of rider and steed beyond peradventure.

“Can it be that my flight is unsuspected?” he asked himself, while he crouched on the ground, uncertain which way to move, and yet feeling that something of the kind must be done.

It was useless to speculate, and, since his foes appeared to be directly in his front, he turned to the right, and began gliding slowly forward, fearful that the beating of his heart would betray him at every inch.

But the marvellous good fortune which had attended him thus far was not quite ready to desert him. With a care and caution beyond description, he advanced foot by foot until he drew a deep sigh of relief at the knowledge that that particular group of red men was no longer in front, but to the left and somewhat to the rear.

“If there are no more,” he thought, “it begins to look as if I might succeed after all.”

But his rejoicing was premature. Not only did he catch the sound of a horse’s hoofs, but 68 they were directly before him, and coming as straight for the spot where he was crouching as if the animal were following a mathematical line.

One of the Comanches was riding through the mesquite bush, and if the youth stayed where he was he must be trampled by the mustang, unless the animal was frightened into leaping aside and thus betraying him to his master.

“Very well,” muttered Avon, “if it comes to that, I know how to manage you.”

As the thought passed through his mind, he reached to his holster and drew his revolver.

At this moment the steed halted, though he gave no sniff or sign that he had learned of the stranger so close in front. Believing a collision inevitable, Avon straightened up, with his weapon firmly grasped.

But before he could use it the rider slipped to the ground, and the next moment drew a match along the side of his leggings. As the tiny flame shone out in the gloom, he held it up in front of his face to light the cigarette between his lips.

As a rule the American Indian is not partial to cigarette smoking, that being a vice that he is willing to leave to his more civilized brother; but the Comanche in front of Avon Burnet, and so near him, left no doubt of his purpose.

As the tiny flame burned more brightly, he shaded it with his hands and puffed the twisted roll of tobacco, like one who knew how liable the blaze was to be blown out by the wind that rustled among the mesquite bushes. He was such an expert at the business, however, that he met with no difficulty.

The glow of the flame shone between the fingers, where they slightly touched each other, giving them a crimson hue, while the point of the nose, the eyes, and the 70 front of the face were revealed almost as distinctly as was the countenance of the warrior whom Dinah discovered in the act of firing the roof of the cabin.

This Comanche was more ill-favored than the other and was in middle life. There was something in his appearance which gave the youth the suspicion that he was the chief or leader of the band of raiders, though there could be no certainty on that point.

Nothing would have been easier than for Avon, from where he stood, to shoot down the savage and appropriate his horse for himself. There was an instant when he meditated such a step, but though many a veteran of the frontier would have seized the chance with eagerness, he shrank from such a deliberate taking of human life.

The youth had already shown his pluck and readiness to use his weapon when necessary, but he could not justify himself in an act like the one named.

But he did not mean to stand idle when there was a call for instant and decisive action.

While the Comanche used his two hands in manipulating his match and cigarette, his rifle leaned against the limbs of one of the largest mesquite bushes, where he could snatch it up without stirring a foot.

It was not to be supposed that he had dismounted for the purpose of kindling his cigarette, for he could have done that on the back of his mustang, as well as when on the ground. He must have decided that he was nigh enough to the other warriors to light his tobacco before joining them on foot.

The youth was sure the steed before him was a fine one, for it is rare to see one of those people without an excellent horse, and he resolved to capture it.

At the instant the match was at its best, and the point of the cigarette was glowing red, Avon stepped toward the motionless steed, passing along the side which was furthest from his master. The beast saw him on the instant, and gave a slight whinny and recoiled.

His master spoke sharply, while the cigarette was between his teeth. Not suspecting 72 the cause of his alarm, he supposed it was trifling and gave it no attention. But when his animal, with a loud snort, wheeled and started off on a gallop, the Indian threw down his match, called out angrily, and, grasping his gun, sprang forward to intercept him.

It will be remembered that the darkness was more dense in the mesquite bush than on the open prairie, and, although he caught a glimpse of the vanishing mustang, he saw nothing of the figure on his back, for the reason that, when the nimble youth vaulted thither, he threw himself forward on his neck.

The Indian must have been astonished by the action of his animal, but he probably concluded he would not wander far, and would be within reach in the morning when needed. So he refrained from attempting anything like pursuit, which would have been foolish under the circumstances.

It was a clever exploit on the part of Avon Burnet, and he could not repress a feeling of exultation over the success. Boldness, dash, and peculiarly favoring circumstances had taken him through the Comanche lines, 73 when a repetition of the attempt would fail ninety-nine times out of a hundred.

But while he was justified in being grateful, there was enough serious business still before him. He could not forget that the friends in the cabin were in dire peril and no time ought to be wasted in bringing them relief.

The first indispensable act was to locate himself, so as to gain an idea of the points of the compass, without which it was beyond his power to reach the camp of his friends.

A brief walk brought the horse out of the bush and he stood on the open prairie. The mustang was without saddle or bridle, except a single buffalo thong, that was twisted over his nose and by which his master guided him. Avon had ridden the animals in the same way, and since this mustang became tractable the instant he felt anyone on his back, such an equestrian as the young Texan met with no difficulty whatever.

But he realized that a serious difficulty confronted him when he attempted to locate himself. The flurry in the bush had so mixed 74 up his ideas of direction, that he was all at sea.

Not a star twinkled in the cloudy sky, nor could he tell in what quarter of the heavens the moon was hidden. Looking in the supposed direction of the cabin, he saw only gloom, while it was equally dark when he gazed toward the spot where he believed the camp of the cowboys lay.

Between the home of Captain Shirril and the spot where his men awaited his coming were several elevations and depressions of land, so that had the Texans been burning a fire, as was likely, it would not show until more than half the intervening distance was passed. The cattle were herded to the northward, so that in the event of a stampede it was easier to head them on the right course over the Great Cattle Trail.

A person placed in the situation of young Burnet is apt to go astray, no matter how extended his experience in wandering abroad at night, unless he is able to start right. This was the difficulty with Avon, who was too wise to depend upon what 75 impressions took possession of him, since it is almost the invariable rule that such impressions are wrong.

There was one faint hope: the Comanches in the vicinity of the cabin had been indulging in shouting and firing their guns. These sounds would prove of great help, but to his dismay, though he sat for several minutes motionless on his mustang and listening, he heard nothing of the kind.

He knew the wind was unfavorable, but he was compelled to believe that he had ridden much further than he first supposed, in order to be beyond reach of the reports. After mounting his mustang, he had sent him scurrying on a dead run through the bush, and kept it up for several minutes, before emerging into the open country: that was sufficient to take him a long way and, as he believed, excluded the one means of guidance which otherwise would have been his.

“Helloa! what does that mean?”

In peering around in the gloom, he saw, apparently a long way off to the left, a star-like point on the prairie, which shone out 76 with an increasing gleam. Wondering what it could signify, he sat for a minute or two, attentively watching it, but unable to solve the interesting question.

“These Comanches are as fond of smoking as are our men, and I suppose one of them has some trouble in lighting his pipe or cigarette––helloa! there it goes!”

The light which was so interesting to him suddenly went out, and all was blank darkness again.

He waited and looked for several minutes, but it did not reappear. At the moment it vanished, he fancied he heard a slight sound, but it was too indefinite to identify.

Had the young man but known that the light which he had seen was burning on the roof of his own home, and that it was Dinah who extinguished it so abruptly, he would have shaped his course far differently.

Avon Burnet waited several minutes after the light went out, in the hope that it would reappear and give him an indication of its nature and cause; but darkness continued, and he concluded that his first suspicion was right: some warrior in riding over the prairie had halted to light his cigar or pipe, and then ridden on to join his comrades near the cabin.

The youth was in the situation of the mariner who finds himself adrift in mid-ocean, without compass or rudder. Neither the sky nor the ground gave him any help, and in order to reach the camp of his friends he must, under Heaven, rely upon his own skill.

“There’s one thing certain,” he concluded, “I shall never get there without making a 78 break. I have secured a pretty good horse, and I may as well turn him to account.”

Heading in the direction which seemed right, he tapped the ribs of the mustang with his heels, and he broke at once into a sweeping gallop, which, if rightly directed, was sure to carry him to his destination in a brief while.

Though it was too much for the young man to believe he was following the true course, he thought it was near enough for him to discover the variation before riding far. He ought to reach the crest of some elevation which would so extend his view that he would catch the gleam of the camp fire of the cattlemen.

As the pony galloped forward with that swinging gait which he was able to maintain for hours without fatigue, the rider glanced to the right and left, in front and rear, on guard lest he ran into unexpected danger, and guarding against the approach of one or more of his foes. His horse was tractable, but the rider was disturbed now and then by his actions.

While going with his swift gait, he occasionally checked his speed so abruptly that, had the young Texan been a less skilful equestrian, he would have pitched over his head. At such times he pricked his ears, and snuffed and threw up his head, as though frightened at something. But strive all he could, Avon failed to discover the cause of this peculiar behavior. He could neither hear nor see anything to explain it.

Our young friend was so keenly on the alert that he was quick to notice that they were ascending quite a swell in the plain. He drew the mustang down to a walk, and when at the highest point of the elevation, brought him to a stand-still.

No poor sailor, floating on a plank, ever strove harder to pierce the gloom in quest of a friendly light, than did Avon. His first glance in the direction which seemed to him to be right failed to show that which he longed to see. Then he slowly swept the horizon with the same searching scrutiny.

Not the first star-like glimmer rewarded him. Blank darkness enclosed him on every 80 hand. It was right above, below, to the right and left and to the front and rear.

“Well, I’ll be shot if this doesn’t beat everything!” was his exclamation, when he came to understand his helplessness; “it looks as if I would have done the folks a great deal more good if I had stayed with them.”

Slipping down from the back of his mustang, which he took care to hold by means of the halter, Avon pressed his ear to the earth, as is the practice of those in a similar situation.

At first he thought he detected the sounds of hoofs, but the next moment he knew it was only fancy. The better conductor in the form of the ground told him no more than did the gloom that surrounded him.

While thus engaged, the mustang tugged at the rope, as if wishing to free himself. He must have felt that he was controlled by a strange hand, but his efforts were easily restrained.

As nearly as Avon could judge, he had travelled more than two miles since leaving the cabin, so that, provided he had followed 81 the proper course, he must have passed half the distance. But if that were the case, he ought to see signs of the camp. It is the custom of the cattlemen, when on the move, to keep a lantern suspended from the front of the provision wagon, to serve as a guide for the rest, and this ought to be visible for several miles to one in his elevated position.

Holding the thong in one hand, the youth now pointed his Winchester toward the sky and discharged several barrels, in the hope that the reports would reach the ears of the Texans and bring a response from them. The mustang did not stir a muscle; he was so accustomed to that sort of thing that his nerves were not disturbed.

This appeal was equally futile, and, as Avon flung himself again upon the back of his horse, a feeling akin to despair came over him.

“Perhaps it was quite an exploit to get through the Comanche lines without harm,” he said to himself, “but of what avail? I shall wander round and round until daylight, with no more knowledge of where I am than 82 if I were groping among the Rocky Mountains; and, long before the rise of sun, the fate of Uncle Dohm and the folks will be settled.”

A feeling of exasperation succeeded his depression of spirits. It was beyond endurance that he should be so near help and yet be unable to secure it. If he could but gain an inkling of the right course, he would dart across the prairie with the speed of an arrow.

He had neglected no possible means of informing himself. Recalling the direction of the wind, he strove to make use of that; but as if even the elements had united against him, he was not long in discovering that the wind was fitful and changing, and his attempt to use it as a guide had much to do with his going so far astray.