The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Arkansaw Bear, by Albert Bigelow Paine

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Arkansaw Bear

A Tale of Fanciful Adventure

Author: Albert Bigelow Paine

Illustrator: Frank Ver Beck

Release Date: March 10, 2009 [EBook #28302]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ARKANSAW BEAR ***

Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music by Linda

Cantoni(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

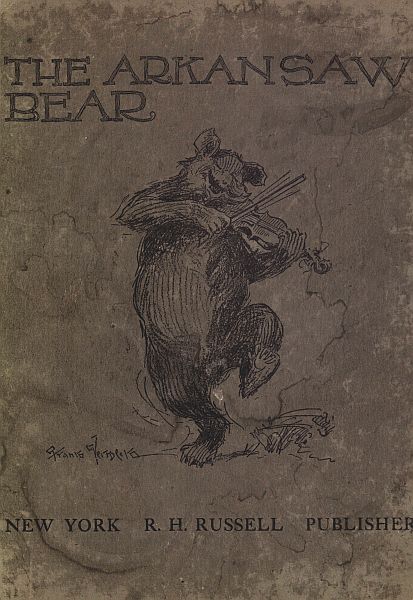

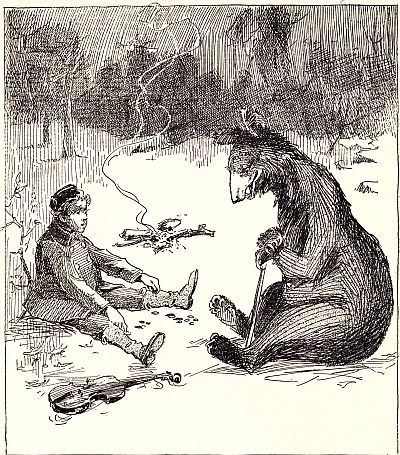

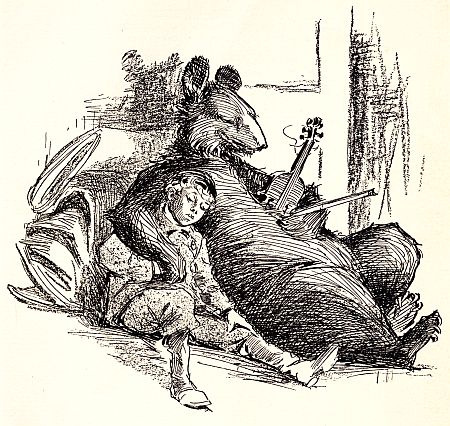

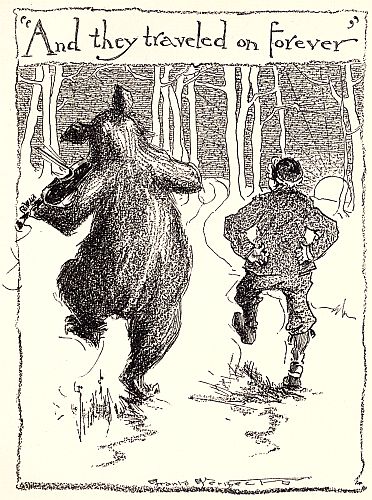

BOSEPHUS AND HORATIO

BOSEPHUS AND HORATIO

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Meeting of Bosephus and Horatio | 11 |

| II | The First Performance | 20 |

| III | Horatio and the Dogs | 29 |

| IV | The Dance of the Forest People | 38 |

| V | Good-bye to Arkansaw | 46 |

| VI | An Exciting Race | 55 |

| VII | Horatio's Moonlight Adventure | 64 |

| VIII | Sweet and Sour | 73 |

| IX | In Jail at Last | 83 |

| X | An Afternoon's Fishing | 92 |

| XI | The Road Home | 101 |

| XII | The Bear Colony at Last. The Parting of Bosephus and Horatio | 111 |

He listened more intently.

It was the "Arkansaw Traveller" and close at hand. The little boy tore hastily through the brush in the direction of the music. The moon had come up, and he could see quite well, but he did not pause to pick his way. As he stepped from the thicket out into an open space the fiddling ceased. It was[12] bright moonlight there, too, and as Bosephus took in the situation his blood turned cold.

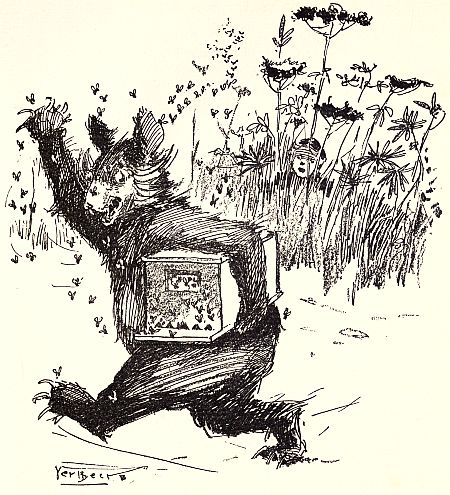

In the center of the open space was a large tree. Backed up against this tree, and looking straight at the little boy, with fiddle in position for playing, and uplifted bow, was a huge Black Bear!

Bosephus looked at the Bear, and the Bear looked at Bosephus.

"Who are you, and what are you doing here?" he roared.

"I—I am Bo-se-Bosephus, an' I—I g-guess I'm l-lost!" gasped the little boy.

"Guess you are!" laughed the Bear, as he drew the bow across the strings.

"An-an' I haven't had any s-supper, either."

"Neither have I!" grinned the Bear, "that is, none worth mentioning. A young rabbit or two, perhaps, and a quart or so of blackberries, but nothing real good and strengthening to fill up on." Then he regarded Bosephus reflectively, and began singing as he played softly:—

"No hurry, you know. Be cool, please, and don't wiggle so."

But Bosephus, or Bo, as he was called, was very much disturbed. So far as he could see there was no prospect of supper for anybody but the Bear.

"You'll forget all about supper pretty soon," continued the Bear, fiddling.

"My name is Horatio," he continued. "Called Ratio for short. But I don't like it. Call me Horatio, in full, please."[13]

"MAYBE YOU CAN PLAY IT YOURSELF."

"MAYBE YOU CAN PLAY IT YOURSELF."

"Oh, ye-yes, sir!" said Bo, hastily.

"See that you don't forget it!" grunted the Bear. "I don't like familiarity in my guests. But I am clear away from the song I was singing when you came tearing out of that thicket. Seems like I never saw anybody in such a hurry to see me as you were.

Bo was very fond of music, and as Horatio drew from the strings the mellow strains of "The Arkansaw Traveller" he forgot that both he and the Bear were hungry. He could dance very well, and was just about to do so as the Bear paused.

"Why don't you play the rest of that tune, Horatio?" he asked, anxiously.

"Same reason the old man didn't!" growled the Bear, still humming the air,

"Why!" continued Bo, "that's funny!"

"Is it?" snorted Horatio; "I never thought so!

"Maybe you can do what the stranger did, Bosephus—maybe you can play it yourself, eh?" grunted the huge animal, pausing and glowering at the little boy.

"Oh, no, sir—I—I—that is, sir, I can only wh-whistle or s-sing it!" trembled Bo.

"What!"

"Y-yes, sir. I——"

"You can sing it?" shouted the Bear, joyfully, and for once forgetting to fiddle. "You don't say so!"[15]

"Why, of course!" laughed Bo; "everybody in Arkansaw can do that. It goes this way:—

When Bo had finished, Horatio stood perfectly still for some moments in astonishment and admiration. Then he came up close to the little boy.

"Look here, Bo," he said, "if you'll teach me to play and sing that tune, we'll forget all about that sort o' personal supper I was planning on, and I'll take you home all in one piece. And anything you want to know I'll tell you, and anything I've got, except the fiddle, is yours. Furthermore, you can call me Ratio, too, see?

Bo brightened up at once. He liked to teach things immensely, and especially to ask questions.

"Why, of course, Ratio," he said, condescendingly; "I shall be most happy. And I can make up poetry, too. Ready, now:—

"Wait, Bo! wait till I catch up!" cried Horatio, excitedly. "Now!"

"Hold on, Ratio. I want to ask a question!"[16]

"All right! Fire away! I couldn't get any further anyhow."

"Well," said Bo, "I want to know how you ever learned to play the fiddle."

Horatio did not reply at first, but closed his eyes reflectively and drew the bow across the string softly.

"I took a course of lessons," he said, presently, "but it is a long story, and some of it is not pleasant. I think we had better go on with the music now:—

"Go right on with the rest of it," said Bo, hastily.

"But I say, Ratio," interrupted Bo again, "how did it come you never learned to play the second part of that tune?"

Horatio scowled fiercely at first, and then once more grew quite pensive. He played listlessly as he replied:—

"Ah," he said, "my teacher was—was unfortunate. He taught me to play the first part of that tune. He would have taught me the rest of it—if he had had time."

Horatio drew the bow lightly across the strings and began to sing, in a far-away voice:—

"Oh!" said Bo; "and w-what happened, Horatio?"

Horatio paused and dashed away a tear.

"It happened in a lonely place," he said, chewing reflectively,[17] "a lonely place in the woods, like this. We were both of us tired and hungry and he grew impatient and beat me. He also spoke of my parents with disrespect, and in the excitement that followed he died."

"Oh!" said Bo.

"Yes," repeated Horatio, "he died. He was such a nice man—such a nice fat Italian man, and so good while—while he lasted."

"Oh!" said Bo.

Horatio sighed.

"His death quite took away my appetite," he mused. "I often miss him now, and long for some one to take his place. I kept this fiddle, though, and he might have been teaching me the second part of that tune on it now if his people hadn't missed him—that is, if he hadn't been impatient, I mean."

"Oh, Ratio!" said Bo, "I will teach you the tune all through! And I will never be the least bit impatient or—or excited. Are you ready to begin, Ratio?"

"All ready! Play."

"That was very nice, Bo, very nice indeed!" exclaimed Horatio, as they finished. "Now, I am going to tell you a secret."

"Oh!" said Bo.

"I have a plan. It is to start a colony for the education and improvement of wild bears. But first I am going to travel and see the world. I have lived mostly with men and know a good deal of their taste—tastes, I mean—and have already travelled in some of the States. After my friend, the Italian, was gone, I tried to carry out his plans and conduct our business alone. But[18] I could only play the first part of that tune, and the people wouldn't stand it. They drove me away with guns and clubs. So I came back to the woods to practice and learn the rest of that music. My gymnastics are better—watch me."

Horatio handed Bo his fiddle and began a most wonderful performance. He stood on his head, walked on his hands, danced on two feet, three feet, and all fours. Then he began and turned somersaults innumerable. Bo was delighted.

"It wasn't because you couldn't play and perform well enough!" he cried, excitedly. "It was because you went alone, and they thought you were a crazy, wild bear. If I could go along with you we could travel together over the whole world and make a fortune. Then we could buy a big swamp and start your colony. What do you say, Ratio? I am a charity boy, and have no home anyway! We can make a fortune and see the world!"

At first Ratio did not say anything. Then he seized Bo in his arms and hugged him till the boy thought his time had come. The Bear put him down and held him off at arm's length, joyously.

"Say!" he shouted. "Why, I say that you are a boy after my own heart! We'll start at once! I'll take you to a place to-night where there are lots of blackberries and honey, and to-morrow we will set forth on our travels. Here's my hand as a guarantee of safety as long as you keep your agreement. You mean to do so, don't you?"

"Oh, yes," said Bo.

"And now for camp. We can play and sing as we go."

As the little boy took Horatio's big paw he ceased to be even the least bit afraid. He had at last found a strong friend, and was going forth into the big world. He had never been so happy in his life before.[19]

"All right, Ratio!" he shouted. "One, two, three, play!"

And Ratio gave the bow a long, joyous scrape across the strings, and thus they began their life together—Bosephus whistling and the Bear playing and singing with all his might the fascinating strains of "The Arkansaw Traveller":—

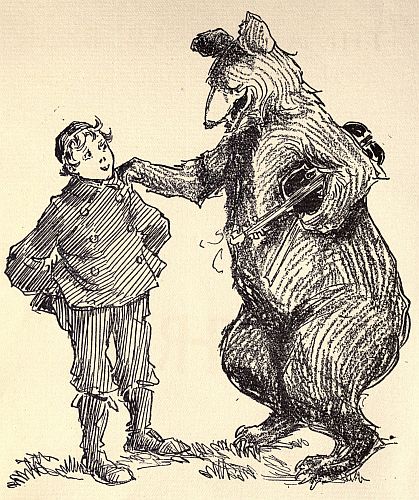

The Bear opened the other eye, and once more reached for his fiddle. This time he got hold of it, but before his other paw touched the bow he was asleep again. Bo waited a moment. Then he suddenly began singing to the other part of the tune:[21]—

Before Bosephus finished the first two lines of this strain Horatio was sitting up straight and fiddling for dear life.

"Once more, Bo, once more!" he shouted as they finished.

They repeated the music, and Horatio turned two handsprings without stopping.

"Now," he said, "we will go forth and conquer the world."

"I could conquer some breakfast first," said Bo.

"Do you like roasting ears?"

"Oh, yes," said Bo.

"Well, I have an interest in a little patch near here—that is, I take an interest, I should say, and you can take part of mine or one of your own if you prefer. It really doesn't make any difference which you do just so you take it before the man that planted it is up."

"Why," exclaimed the boy as they came out into a little clearing, "that is old Zack Todd's field!"

"It is, is it? Well, how did old Zack Todd get it, I'd like to know."

"Why—why I don't know," answered Bo, puzzled.

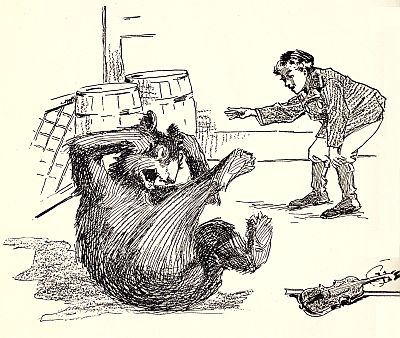

"ONCE MORE, BO, ONCE MORE"

"ONCE MORE, BO, ONCE MORE"

"Of course not," said the Bear. "And now, Bosephus, let me tell you something. The bears owned that field long before old Zack Todd was ever thought of. We're just renting it to him on shares. This is rent day. We don't need to wake Zack[23] up. You get over the fence and hand me a few of the best ears you can get quick and handy, and you might bring one of those watermelons I see in the corn there, and we'll find a quiet place that I know of and eat it."

Bo hopped lightly over the rail fence, and, gathering an armful of green corn, handed it to Horatio. Then he turned to select a melon.

"Has Zack Todd got a gun, Bosephus?" asked the Bear.

"Yes, sir-ee. The best gun in Arkansaw, and he's a dead shot with it."

"Oh, he is. Well, maybe you better not be quite so slow picking out that melon. Just take the first big one you see and come on."

"Why, Zack wouldn't care for us collecting rent, would he?"

"Well, I don't know. You see, some folks are peculiar that way. Zack might forget it was rent day, and a man with a bad memory and a good gun can't be trusted. Especially when he's a dead shot. There, that one will do. Never mind about his receipt—we'll mail it to him."

Bo scrambled back over the fence with the melon and hastened as fast as he could after Horatio, who was already moving across the clearing with his violin under one arm and the green ears under the other.

"Wait, Ratio," called the little boy. "This melon is heavy."

"Is that a long range gun, Bo?" called back the Bear.

"Carries a mile and a half."

"Can't you move up a little faster, Bo? I'm afraid, after all, that melon is bigger than we needed."

The boy was fat and he panted after his huge companion.

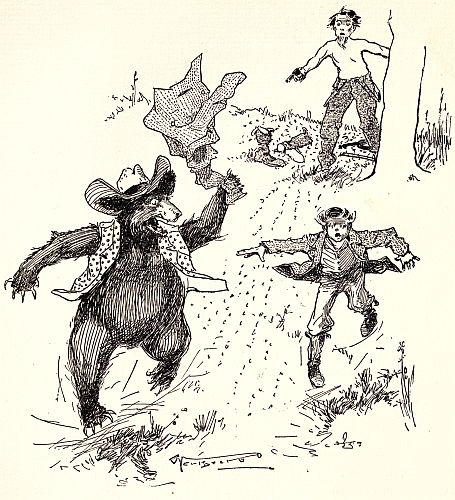

Suddenly there was a sharp report, and Bosephus saw a little tuft of fur fly from one of his companion's ears. Horatio dodged frantically and dropped part of his corn.[24]

CONQUERING THE WORLD.

CONQUERING THE WORLD.

"Run zigzag, Bo!" he called, "and don't drop the melon. Run zigzag. He can't hit you so well then," and Horatio himself began such a performance of running first one way and then the other that Bo was almost obliged to laugh in spite of their peril.

"Is this what you call conquering the world, Ratio?" Then, as he followed the Bear's example, he caught a backward glimpse out of the corner of his eye.

"Oh, Ratio," he called, "the whole family is after us. Zack Todd, and old Mis' Todd, and Jim, and the girls."

"How many times does that gun shoot?"

"Only once without loading."

"Muzzle loader?"

"Yep," panted Bo. "Old style."

"Good! Hold on to that melon. We'll get to the woods yet."

But Horatio was mistaken, for just as they dashed into the edge of the timber, with the pursuers getting closer every moment, right in front of them was a high barbed-wire fence which the Todd family had built around the clearing but a few days before. The Bear dropped his corn, and the boy carefully, but with some haste, put down the melon. Then they turned. The Todd family was just entering the woods—old Zack and the gun in front. He had loaded it and was putting on the cap as he ran.

"What shall we do, Bo, what shall we do now?" groaned Horatio.

The situation was indeed desperate. Their pursuers were upon them, and in a moment more the deadly gun would be levelled. Suddenly a bright thought occurred to Bo.

"I know," he shouted; "dance! Horatio! dance!"[26]

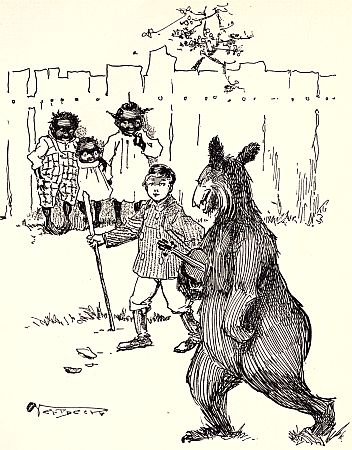

"DANCE! HORATIO, DANCE!"

"DANCE! HORATIO, DANCE!"

Horatio still had his fiddle under his arm. He threw it into position and ran the bow over the strings. In a second more he was playing and dancing, and Bo was singing as though it were a matter of life and death, which indeed it was:—

The Todd family stood still at this unexpected performance and stared at the two musicians. Old man Todd leaned his gun against a tree.

The Todd family were falling into the swing of the music. Old Mis' Todd and the girls were swaying back and forth and the men were beating time with their feet. Suddenly Bosephus changed to the second part of the tune.

The first line of this had started the Todd family. Old Zack swung old Mis' Todd, and Jim swung the girls. Then all[28] joined hands and circled to the left. They circled around Bosephus and Horatio, who kept on with the music, faster and faster. Then there was a grand right and left and balance all—every one for himself—until they were breathless and could dance no more. Horatio stopped fiddling and when old man Todd could catch his breath he said to Bo:—

"Look a-here; that Bear of yours is a whole show by himself, and you're another. Anybody that can play and sing like that can have anything I've got. There's my house and there's my cornfield; help yourselves."

Bo thanked him and said that the corn and the melon already selected would do for the time. To oblige them, however, he would take up a modest collection. He passed his hat and received a silver twenty-five cent piece, a spool of thread with a needle in it, a one-bladed jack-knife and two candy hearts with mottoes on them—these last being from the girls, who blushed and giggled as they contributed. Then he said good-by, and the Todd family showed them a gate that led into the thick woods. As the friends passed out of sight and hearing Bosephus paused and waved his handkerchief to the girls. A little later Horatio turned to him and said, impressively:—

"That is what I call conquering the world, Bosephus. We began a little sooner and more abruptly than I had expected, but it was not badly done, and, all things considered, you did your part very well, Bosephus; very well indeed."

"I say, Ratio," interrupted Bo. "Suppose we move on and give Mr. Jay Bird a chance?"

Horatio grunted and rose heavily. After their adventure with the Todd family they had come to a pleasant spot in the woods by a clear stream of water. Bo, who had some matches in his pocket, had kindled a fire and roasted some of the corn, much to the disgust of Horatio, who disliked fire and asked him why he didn't roast the watermelon, too, while he was about it.[30] Then they had eaten their breakfast together and taken a brief rest before setting forth again on their travels. A jay bird was waiting to peck the gnawed ears and melon rinds. He stared at the strange pair as they strolled away through the trees, the Bear continuing his favorite melody.

"Ratio," said Bo, pausing suddenly, "what is that I hear scurrying through the bushes every now and then?"

"Friends of mine, likely."

"Friends! What friends?"

"Oh, everything, most. Wild cats, wolves, foxes and a few wild bears, maybe."

"Wildcats! Bears! Wolves!"

"Why, yes. Often when I play in the moonlight they come out and dance for me."

"Oh!" said Bo.

"I have them all dancing together, sometimes. I'll have them dance for you before long."

"Oh, Ratio, will you?"

"Yes. It's a lot of fun, but there's no money in it, and that's what we're after now, Bo. We're going to buy that swamp, you remember, and start that bear colony."

Bosephus was about to reply when Horatio paused and listened. There was the distant sound of dogs barking.

"Hello!" said Bo. "We're coming to somewhere. Now we'll give our first regular performance. Come on, Ratio!"

Horatio hesitated.

"How many dogs do you suppose there are, Bo?" he asked anxiously.

"About a dozen, I should think, big and little."

"Little dogs, Bo? Little snapping dogs?"

"That's what it sounds like, and some hounds and a big dog or two. You don't mind dogs, do you?"[31]

"HELLO!" SAID BO, "WE'RE COMING TO SOMEWHERE."

"HELLO!" SAID BO, "WE'RE COMING TO SOMEWHERE."

"Oh, no, not in the least—but it's most too soon after breakfast to give a performance, and besides, all that noise would spoil the music."

But the little boy, who still had in his pocket the two candy hearts that had been given to him by the Todd girls, walked ahead proudly.

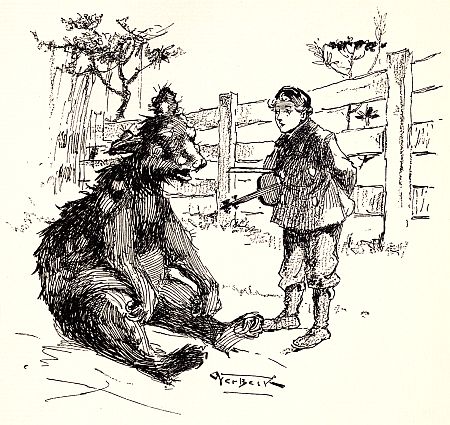

"You trust to me!" he said, flourishing a large stick. "I'll stop their noise pretty quick. I'm not afraid of dogs!"

The Bear followed some steps behind, looking ahead warily.

"I'm not afraid, either, you know," he said, anxiously. "Only when there are so many of them they get me mixed up on my notes and one of them once had the ill manners to nip quite a piece out of my left hind leg."

Presently they came into an open space and plump upon a little crossroads village. A gang of dogs gambolled upon the common, chasing stray geese and barking loudly. Horatio paused.

"Come back, Bo," he whispered. "There's no money in that crowd."

But Bosephus was already some distance ahead, stick in hand, and the dogs had spied him. They ceased barking for a moment and two or three of the larger ones ran away. Then the little dogs began yelping again and came on in a swarm. Bo made at them with his stick, but they dodged past him, and in a moment more were circling and snapping around Horatio, who was waving his violin wildly with one paw and slapping like a man killing mosquitoes with the other.

"Quick, Bo!" he shouted. "Quick! Help! Murder!"

The little boy wanted to laugh, but ran up instead and began striking among the bevy of dogs that were torturing his friend. Some of them howled and ran off a few paces. Then they came flocking back. Suddenly Horatio thrust his violin[33] into Bo's hand and ran swiftly toward a large tree a few yards distant. The curs followed and jumped high into the air after him as he scrambled up to the lower limbs.

Bosephus hurried after them and struck at them so fiercely with his club that they ran yelping away. A number of villagers, attracted by the commotion, were now appearing from all quarters.

"Here come the people, Ratio," said Bo, grinning. "Now we can perform."

"All right, Bo," whispered the Bear, "but if you'll kindly hand me up that fiddle I believe I'll perform right where I am."

The boy passed up the violin and the Bear struck a few notes. By this time the people had collected. There was a blacksmith with a leather apron, and a painter with all colors of paint on his clothes. Behind them there came a woman with dough on her hands and another carrying a baby. Other men and women followed in the procession, and a dozen or so children of all ages. They halted a little way from the tree and stood staring. Horatio sat astride a big limb and commenced playing. Suddenly the boy threw back his head and began to sing:—

The children drew up close at the first line and held their breath to listen. As the boy paused they shouted and screamed with laughter at the sight of Horatio fiddling in the forks of the tree. The dogs sat in a row and howled plaintively.

"Sing some more," cried the woman with the baby; "it amuses my little Joey."[34]

BOSEPHUS HURRIED AFTER THEM AND STRUCK AT THEM.

BOSEPHUS HURRIED AFTER THEM AND STRUCK AT THEM.

"More! more!" shouted the people as they formed into cotillons and reels. "Sing us some more!"

"Wait! wait!" called the woman with the baby under her arm, "I'm all out of breath."

"No, no!" shouted the children and all the others. "Go on! Go on!"

So once more and yet another time the unwearied musicians repeated their performance, and then Bo politely passed his hat to the dancers. When he had been to each one his hat was heavy with some money and many useful articles.

"Bring your Bear down out of the tree," said the blacksmith, "and we will give you a feast on the common."

Bo beckoned to Horatio to climb down, but the big fellow hesitated.

The temptation of a feast, however, was too much for him.

ONCE MORE AND YET ANOTHER TIME.

ONCE MORE AND YET ANOTHER TIME.

That night, when they had both danced again for the people and Horatio had given them an acrobatic exhibition, they strolled away through the evening loaded down with luxuries of all kinds. The villagers went with them to the outskirts, and called good luck after them. As they passed into the quiet[37] shadows of the forest they once more heard the barking of dogs in the distance behind them.

"We have had a good day, Bosephus," said Horatio, with a long sigh of satisfaction. "We are on the road to fortune. To be sure, there are little thorns along the way—"

"Dogs, for instance—and guns."

"Trifles, Bosephus; trifles. Don't give them a second thought. Of course you are only a little boy as yet, and will outgrow these fears."

"And learn to climb trees."

"I hope you don't think I climbed that tree out of fear, Bosephus. I merely went up there to get a better view of my audience. One should always rise above his audience. And now let us sing softly together as we go. It will rest us after our day of conquest."

And touching the strings lightly and singing softly together, the friends sought leisurely their evening camp. Here and there a light rustle in the bushes showed that the forest people were listening, and the leaves of the forest whispered in time to their melody.

"You see, Bo, if you wore clothes like mine you wouldn't have to do that."

"And if the dog that did that had got his teeth into your clothes, you'd have wished they were like mine. Maybe that's why you didn't give him a chance."

"Let's count the money, Bo."

So then they counted up their day's receipts. There was something more than a dollar in all, and Horatio was much pleased.[39]

THEIR CAMP-FIRE HAD DIED DOWN.

THEIR CAMP-FIRE HAD DIED DOWN.

"I tell you, Bo," he said excitedly, "we've made a fine start. By and by we will earn two or three times that much every day, and be able to start our bear colony before you know it."

The little boy fondled the coins over and over. They were the first he had ever earned.

"Ratio," he said at last, "don't you suppose when we get a lot of money—a big lot, I mean—we might give some to those people I used to live with?"

Horatio scowled.

"I thought you said they didn't treat you well and you had to run away."

"Yes, of course, Ratio; but then they were so poor and maybe they'd have been better to me if I had been able to earn money for them. They did take me out of the poor house, you know, and—"

"And you tried to get back again and got lost and fell in with me. Now you are sorry and want to go to them, do you?" and the Bear snorted so fiercely that the little boy trembled.

"Oh, no! Not for the world! I never was so happy in all my life, only I just thought—"

"Then don't think, Bo," interrupted Horatio, gently. "You are only a little boy. I will do the thinking for this firm. Now for a song, Bo, to soothe us."

So then they played and sang softly together while the moon rose and the fire died out, and the boy poured the money from hand to hand, lovingly.

"Bosephus," said his companion, as they paused, "were those people you lived with nice people? Nice fat people, I mean?"

"Not very. Old Mr. Sugget might have been pretty fat if he'd had more to eat, but Mis' Sugget wasn't made to get fat, I know. It wasn't her build."[41]

"It was the old man that abused you, wasn't it?"

"Well, mostly."

"Knocked you about and half starved you?"

"Sometimes, but then——"

"Wait, please. I have an idea. When we get our bear colony started we'll invite this Sugget party to visit us. We'll feed him—all he can eat. By and by, when he gets fat—how long do you suppose it will take him to get fat, Bo? Fat enough, I mean?"

"Fat enough for what?" shivered Bo.

Horatio drew the horsehair briskly across the strings and looked up at the moon.

"Fat enough to be entertaining," he grinned, and began singing:—

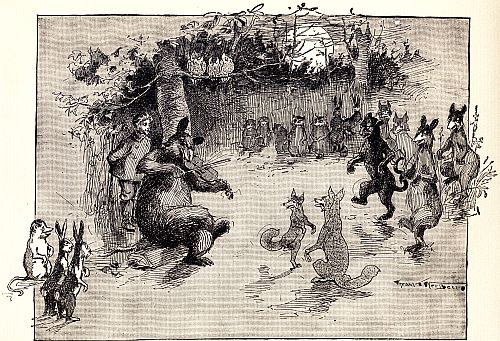

While the Bear played the little boy had been watching a slim, moving shadow that seemed to have drifted out from among the heavier shadows into the half-lit open space in front of them. As the music ceased it drifted back again.

"Play some more, Ratio," he whispered.

Again the Bear played and again the slim shadow appeared in the moonlight and presently another and another. Some of them were slender and graceful; some of them heavier and slower of movement. As the music continued they swung into a half circle and drew closer. Now and then the boy caught a glimpse of two shining sparks that kept time and movement with each. He could hardly breathe in his excitement.

"Look there, Ratio," he whispered.

Horatio did not stir.[42]

"Sh-h!" he said softly. "My friends—the forest people."

The Bear slackened the music a little as he spoke and the shadows wavered and drew away. Then he livened the strain and they trooped forward again eagerly.

Just then the moon swung clear of the thick trees and the dancers were in its full flood. The boy watched them with trembling eagerness.

A tall, catlike creature, erect and graceful, swayed like a phantom in and out among the others, and seemed to lead. As it came directly in front of the musicians it turned full front toward them. It was an immense gray panther.

At any other time Bo would have screamed. Now he was only fascinated. Its step was perfect and its long tail waved behind it, like a silver plume, which the others followed. Two red foxes kept pace with it. Two gray ones, a little to one side, imitated their movements. In the background a family of three bears danced so awkwardly that Bo was inclined to laugh.

"We will teach them to do better than that when we get our colony," he said.

Horatio nodded without pausing. The dancers separated, each group to itself, the gray panther in the foreground. Spellbound, the boy watched the beautiful swaying creature. He had been taught to fear the "painter," as it was called in Arkansaw, but he had no fear now. He almost felt that he must himself step out into that enchanted circle and join in the weird dance.

New arrivals stole constantly out of the darkness to mingle in the merrymaking. A little way apart a group of rabbits skipped wildly together, while near them a party of capering wolves had forgotten their taste for blood. Two plump 'coons and a heavy bodied 'possum, after trying in vain to keep up with the others, were content to sit side by side and look on. Other[43] friends, some of whom the boy did not know, slipped out into the magic circle, and, after watching the others for a moment, leaped madly into the revel. The instinct of the old days had claimed them when the wild beasts of the forest and the wood nymphs trod measures to the pipes of Pan. The boy leaned close to the player.

"The rest of it!" he whispered. "Play the rest of it!"

"I am afraid. They have never heard it before."

"Play it! Play it!" commanded Bo, excitedly.

There was a short, sharp pause at the end of the next bar, then a sudden wild dash into the second half of the tune. The prancing animals stopped as if by magic. For an instant they stood motionless, staring with eyes like coals. Then came a great rush forward, the gray panther at the head. The boy saw them coming, but could not move.

"Sing!" shouted Horatio; "sing!"

For a second the words refused to come. Then they flooded forth in the moonlight. Bo could sing, and he had never sung as he did now.

THE INSTINCT OF THE OLD DAYS HAD CLAIMED THEM.

THE INSTINCT OF THE OLD DAYS HAD CLAIMED THEM.

At the first notes of the boy's clear voice the animals hesitated; then they crept up slowly and gathered about to listen. They did not resume dancing to this new strain. Perhaps they wanted to learn it first. Bo sang on and on. The listening audience[45] never moved. Then Horatio played very softly, and the singer lowered his voice until it became like a far off echo. When Bo sang like this he often closed his eyes. He did so now.

The music sank lower and lower, until it died away in a whisper. The boy ceased singing and opening his eyes gazed about him. Here and there he imagined he heard a slight rustle in the leaves, but the gray panther was gone. The frisking rabbits and the capering wolves had vanished. The red and gray foxes, the awkward bears and the rest of that frolicking throng had melted back into the shadows. So far as he could peer into the dim forest he was alone with his faithful friend.

"Bo," he said presently, "you'll have to have some heavier clothes. Either that or we'll have to go farther South. As for me, you know, I could go to sleep in a hollow tree and not mind the winter, but you couldn't do it, and I don't intend to, either, this year; we're making too much money for that."

Bo laughed in spite of the cold and jingled his pockets. They were more than half full of coin, and he had a good roll of bills in his jacket besides.

"No," he said; "we are getting along too well. We'll be rich by spring if we keep right on. I'm thinking, though, that we'll never be able to get South fast enough if we walk."

"Look here, Bo; you're not thinking about putting me on that cyclone thing they call a train, are you?"[47]

"Well, not exactly, but yesterday where we performed I heard a fellow say that there was a river right close here, and steamboats. You wouldn't mind a steamboat, would you, Ratio?"

"Of course not. I don't mind anything. I've always wanted to ride on one of those trains, only I knew the people would be frightened at me, and as for a steamboat, why, if I should meet a steamboat coming down the road—"

"But steamboats don't come down the roads, Ratio; they go on the water."

"Water! Water that you drink, and drown things in?"

"Of course! And if the boat goes down we'll be drowned, too."

Horatio struck a few notes on the violin before replying.

"Bo," he said presently, "you're a friend of mine, aren't you? A true friend?"

"Yes, Ratio, you know I am."

"Well, then, don't you go on one of those boats. It would grieve me terribly if anything should happen to you. I might not be able to save you, Bo, and then think how lonely I should be." And Horatio put one paw to his eyes and sobbed.

"Oh, pshaw, Ratio! Why, I can swim like everything. I'm not afraid."

"But you couldn't save us both, Bo—I mean, we both couldn't save the fiddle—it would get wet. Think—think of the fiddle, Bo!"

The fire was burning brightly by this time and the little boy was getting warm. He laughed and rubbed his hands and began to sing:—

Horatio stopped short and snorted angrily.

"I want you to understand," he said, sharply, "that I'm not afraid of anything. You'll please remember that night when the forest people danced and you thought your time had come, how I saved you by making you sing. There's nothing I fear. Why if—"

But what Horatio was about to say will never be known, for at that moment there came such a frightful noise as neither of them had ever heard before. It came from everywhere at once, and seemed to fill all the sky and set the earth to trembling. It was followed by two or three fierce snorts and a dazzling gleam of light through the trees. The little boy was startled, and as for the Bear, he gave one wild look and fled. In his fright he did not notice a small shrub, and, tripping over it, he fell headlong into a clump of briars, where he lay, groaning dismally that he was killed and that the world was coming to an end.

Suddenly Bosephus gave a shout of laughter.

"Get up, Ratio," he called, "it's our steamboat! We're right near the river and didn't know it. They're landing, too, and we can go right aboard."

The groaning ceased and there was a labored movement among the briars.

Presently Horatio crept out, very much crestfallen, and picked up the violin, which in his haste he had dropped.

"Bo," he said, sheepishly, "I never told you about it before, but I am subject to fits. I had one just then. They come on suddenly that way. All my family have them and act strangely at times. I'm sure you don't think for a moment that I was frightened just now."

HE FELL HEADLONG.

HE FELL HEADLONG.

"Oh, no, of course not. You merely picked out that briar patch as a good place to have a fit in. Do you always think the[50] world's coming to an end when you are taken that way?"

"We'll go right aboard, Bo; you are a little timid, no doubt, so I'll lead the way." And Horatio stepped out briskly toward the lights and voices and the landing steamer.

A few steps brought them out to the river bank and a full view of the boat that had crept silently around a bend to the woodyard, where it was halting to take on fuel. The gang plank had not been pushed out to the bank as yet, but a white ray of light shot from a small window to the dark shore and looked exactly like a narrow board. The boy and the Bear were both deceived by it, and Horatio in his eagerness to show his bravery did not pause to investigate.

"Take the fiddle, Bo," he said, loftily, "and I'll show you how to get on a boat. You should always be brave, Bosephus."

Bosephus took the instrument and Horatio, with arms extended as a balance, stepped straight out into nothing and vanished. There was a sudden splash, a growl, a scrambling sound in the shallow water and Horatio's head appeared above the bank. Bosephus, at first frightened, was now doubled with laughter.

"Oh, Ratio," he gasped, "how funny of you to try to walk on a moonbeam!"

Horatio shook himself and sniffed angrily. A wide gang plank was now being lowered from the boat, and as it touched the bank the boy stepped quickly aboard, followed by the wet, shambling Bear.

"Hello!" called a voice. "Where did you come from?"

Bo looked up and saw a brawny man with a group of wondering negroes behind him.

"We are travelling," said Bo, "and we want to go down the river. We can pay our way and will make music for you, too."

"Good boy," said the mate. "Go right up and report to the clerk, then come back down here, and after we get this wood loaded we'll give you some supper and you can give us a show."

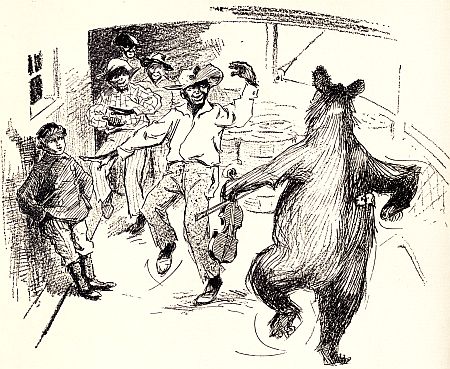

On the upper deck the few passengers gathered around and made much of the arrivals. All asked questions at once, and Bo answered as best he could. Horatio kept silent—he never talked except when he was alone with Bo. The boy kept his hand on the Bear's head, and when the boat backed away and puffed down stream he felt his big friend tremble, but a little later, when they had had a good supper, Ratio's fear passed off, and on the lower deck, where all hands collected, the friends gave an entertainment that not only won for them free passage down the river, but a good collection besides. It was far in the night when the performance ended. The officers, passengers and crew kept calling for more, and the travellers were anxious to accommodate them. The negroes went wild over the music, and patted and danced crazily whenever Horatio played. Finally Bo sang a good night song:—

THE NEGROES WENT WILD OVER THE MUSIC.

THE NEGROES WENT WILD OVER THE MUSIC.

THE LITTLE BOY WAS IN THE LAND OF DREAMS.

THE LITTLE BOY WAS IN THE LAND OF DREAMS.

Bosephus and Horatio were both offered staterooms on the upper deck, but Horatio preferred to sleep outside, and the little boy said he would sleep there also. Horatio sat up for some moments after Bo had stretched himself to rest, looking at the dark wooded banks and the starlight on the water behind them.

"Bo," he said, at last, "we are going to see the world now, sure enough."

"Yes, Ratio," was the sleepy answer.

"Bo, do you suppose our camp fire is still burning back yonder?"

No answer.

"I hate to leave old Arkansaw, don't you, Bo?"

But the little boy was in the land of dreams.

"I tell you, Bo," said Horatio grandly, "there's nothing like travel. You're a lucky boy, Bo, to fall in with me. Why, the way you've come out in the last few months is wonderful. Of course, there is a good deal of room yet for improvement, and there are still some things that you are rather timid of, but when I remember how you looked the first minute I saw you, and then to see the sociable way you sit up and talk to me now, you[56] really don't seem like the same boy, Bosephus, you really don't."

The little boy leaned up close to his companion.

"Ratio," said the little boy, confidentially, "did you really intend to—to have me—you know, Ratio—for—for supper until I taught you the tune? Did you, Ratio?"

Horatio gazed away across a broad cane field, where the first streak of sunrise was beginning to show.

"This is very pleasant travelling," commented Horatio thoughtfully. "It beats walking, at least for speed and comfort. Of course, there are a number of places we cannot reach by boat," he added, regretfully.

"Not in Southern Louisiana, Ratio. I've heard that there's a regular tangle of rivers and bayous all over the country, and that boats go everywhere."

Horatio looked pleased.

"Aren't you glad now, Bo," he said proudly, "that I proposed this boat business? I have always wanted to travel this way. I was afraid at first that you might not take to it very[57] well, and when that whistle blew last night I could see that you were frightened. It was unfortunate that I should have had a fit just then or I might have calmed you. You saw how anxious I was to go aboard. Of course, in being over brave I made a slight mistake. I am always that way. All my family are. One really ought to be less reckless about some things, but somehow none of my family ever knew what fear was. We——"

But just then the boat concluded to land, and the morning stillness was torn into shreds by its frightful whistle. Horatio threw up both hands and fell backward on the deck, where he lay pawing the air wildly. Then he stuffed his paws into his ears and howled as he kicked with his hind feet. Bo stood over him and shouted that there was no danger, but his voice made no sound in that awful thunder. All at once Horatio sprang up and jammed his head under Bo's arm, trembling like a jellyfish. Then the noise stopped, and with one or two more hoarse shouts ceased entirely.

"It's all right, Ratio, come out!" said Bo, trying to stop laughing.

Horatio felt of his ears a moment to see that they were still there, while he looked skittishly in the direction of the dreadful whistle and started violently at the quick snorts of the escaping steam.

"Bo," he said faintly, "do all boats do that?"

"Oh, yes! Some worse than others. This one isn't very bad."

"I'm sorry, Bo, for it is a great drawback to travel where one is subject to fits as I am. It seems to bring them on. And it is not kind of you to laugh at my affliction, either, Bosephus," he added, for Bo had dropped down on the deck, where he was rolling and holding his sides.

HE STUFFED HIS PAWS INTO HIS EARS.

HE STUFFED HIS PAWS INTO HIS EARS.

All at once the boy lay perfectly still. Then he sprang up[59] with every bit of laugh gone out of his face. His left hand grasped the outside of his jacket, while with his right hand he dived down into the inside pocket like mad. The Bear watched him anxiously.

"What is it, Bo? Have you got one, too?" he asked.

"Horatio!" gasped the boy. "Our money! It's gone!"

"Gone! Gone! Where?"

"Stolen. Some of those niggers did it while we were asleep!"

The Bear reflected a moment. Then he said thoughtfully:—

"Do you suppose, Bo, it was that nice fat one?"

"I shouldn't wonder a bit. I saw him watch every penny I took in last night."

Horatio licked out his tongue eagerly.

"Could I have him if it was?" he asked hungrily.

"Have him! How?" said Bo. Then he shuddered. "Oh! no, not that way—of course not. But I'll tell you, Ratio," he added, "we'll make him believe that you can, and frighten him into giving up the money."

Horatio frowned.

"I don't like make-believes," he grumbled. "Can't we let the money go this time and not have any make-believe?"

"Not much—we want that money right now, before the boat lands; then we'll go ashore and get out of such a crowd. Come, Ratio."

No one was stirring on the upper deck as yet, but the crew was collected below where the second mate was shouting orders as the boat swung slowly into the bank. They boy and Bear dashed down the stairs.

"OUR MONEY! IT IS GONE!"

"OUR MONEY! IT IS GONE!"

"Wait!" shouted Bo to the officer. "Somebody on this boat last night stole our money, and I want my Bear to find[61] him. It won't take but a minute, for he can tell a thief at sight when he's mad and hungry, and he's mad now, and hungry for dark meat!" The boy looked straight into the crowd of negroes, while the Bear growled fiercely and fixed his eye on the fat darky.

The crew fell back and the fat darky with a howl started to run.

"That's the one! That's the thief!" shouted Bo, and with a snarl Horatio bounded away in pursuit. Down the narrow gangway to the stern of the boat, then in a circle around a lot of cotton, they ran like mad, the Bear getting closer to the negro every minute. Then back again to the bow in a straight stretch, the thief blue with fright and Horatio's eyes shining with hungry anticipation. The rest of the crew looked on and cheered. Suddenly, as the fat darky passed Bo, he jerked a sack from his pocket and flung it behind him.

"Dar's yo' money! Dar's yo' money!" he shouted. "Call off yo' B'ar!"

But that was not so easy. Bosephus shouted frantically at Horatio, but he did not seem to hear. His blood was up, and his taste for dark meat was stronger than his love of money. As the two came clattering around the second time he was so close to his prey that with a quick swipe he got quite a piece of his shirt. With a wild yell the fat fugitive leaped over into the river and struck out for shore.

Horatio paused. His half open jaws were dripping and his eyes red and fiery with disappointment. Bo went up to him gently.

"Come, Ratio," he whispered.

The Bear paid no heed. He was watching his escaped prey, who had reached the shore and was disappearing in a great canefield.[62]

THE FAT FUGITIVE LEAPED OVER INTO THE RIVER.

THE FAT FUGITIVE LEAPED OVER INTO THE RIVER.

"Come!" Bo whispered again. "We'll go ashore, too."

Horatio wheeled eagerly. The gangplank was being lowered, and he hurried Bo out on it, so that when it touched the bank he was all ready to give chase again.

"No, wait; some music first," said Bo. "I have thought of some new lines for the second part of the tune."

For a moment Horatio hesitated. Then the temptation of the music was stronger even than his appetite, and, throwing his violin into position, he began to play. The passengers, roused by the excitement, had gathered on the upper deck. The crew coming ashore below paused to listen.

The crew cheered and the passengers on the upper deck shouted and waved their handkerchiefs.

"Don't go!" they called. "Don't leave us!" But the friends turned their faces to the East and set out on a broad white road that led away to the sunrise.

"Bo," said the Bear presently, "we are doing well. We are making money, Bo."

"Fifty dollars since we left the boat," said the little boy.

"These fat babies—little darky babies—are very amusing, too, Bosephus, don't you think so?" Horatio added, nodding in the direction of some they were just then passing.

"THESE LITTLE DARKEY BABIES ARE VERY—AMUSING."

"THESE LITTLE DARKEY BABIES ARE VERY—AMUSING."

"I notice that you think so," said Bo, dryly. "If you'll take my advice, though, you won't show any special fondness for them. People might not understand your ways, you know, and[66] besides," he added, with a grin, "I've heard say these darkies down here are mighty fond of bear meat, and there's such a lot of them——"

"Don't you mention it, Bo; I never dreamed of such a thing as you are hinting at."

"Well, you said you were dreaming yesterday when we met that little darky boy, and you nearly tore the jacket off of him before I could wake you up with a club."

Horatio drew his bow hastily across the strings and began singing—

The sun was just setting behind a large, white, old fashioned sugar house, where the bayou turned, and made it look like an ancient castle. The little boy sighed. He had never believed that any country could be so beautiful as this, and he wanted to stay in it forever. Horatio liked it, too. They had played and danced at many of the sugar houses, and the Bear had been given everywhere all the waste sugar he could eat. He was fond of the green cane also, and was nearly always chewing a piece when they were not busy with a performance. But the big fellow had never quite overcome his old savage nature, and the race on the steamboat had roused it more fiercely than ever. The fat pickaninnies were a constant temptation to him, and it had taken all Bo's watchfulness to keep him out of dreadful mischief. Bo never feared for himself. Horatio loved him and[67] had even become afraid of him. It was for Horatio that he feared, for he knew that death would be sure and swift if one of the pickaninnies was even so much as scratched, not to mention anything worse that might happen. Again the little boy sighed as they turned into a clean grassy place and made ready for camp.

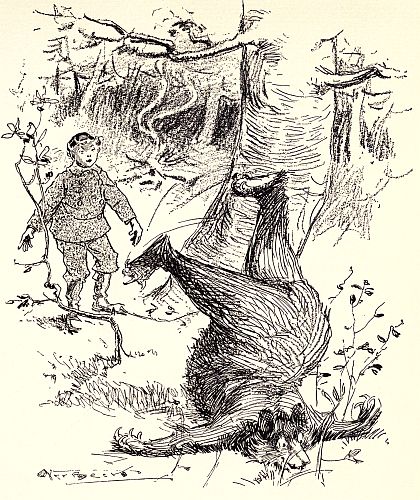

Long after Bosephus was asleep Horatio sat by the dying camp fire, thinking. By and by he rose and walked out to the bank of the bayou and looked toward the sugar house that lay white in the moonlight, half a mile away. Then he went back to where Bo was asleep and picked up the violin. Then he laid it down again, as though he had changed his mind, and slipped away through the shadows in the direction of the old sugar house. He said to himself that, as they were going in that direction and would stop there next day, he might as well see how the road went and what kind of a place it was. He did not own, even to himself, that it was the negro cabins and fat pickaninnies that were in his mind, and that down in his heart was a wicked and savage purpose. Every little way he paused and seemed about to turn back, but he kept on. By and by he drew near the sugar house and saw the double row of whitewashed huts in the moonlight. It was later than he had supposed and the crowds of little darkies that were usually playing outside had gone to bed. He sighed and was about to turn back when suddenly he saw something capering about near the shed of the sugar house. He slipped up nearer and a fierce light came into his eyes. It was a little negro boy doing a hoo-doo dance in the moonlight.

HE SLIPPED AWAY THROUGH THE SHADOWS.

HE SLIPPED AWAY THROUGH THE SHADOWS.

Suddenly the little fellow turned and saw the Bear glaring at him. Horatio was between him and the cabins. The boy gave one wild shriek and dashed through a small open door that led into the blackness of the sugar house, the Bear following[69] close behind. It was one of the old Creole sugar houses where the syrup is poured out into open vessels to cool and harden. The little darky knew his way and Horatio didn't. He stumbled and fell, and growled and tried to follow the flying shadow that was skipping and leaping and begging, "Oh, Mars Debbil! Oh, please, Mars Debbil, lemme go dis time, an' I nevah do so no mo'. Nevah do no mo' hoo-doo, Mars Debbil; oh, please, Mars Debbil, lemme go!"

But Horatio was getting closer and closer and in another moment would seize him. Then, suddenly, something happened. The Bear stumbled and, half falling, stepped into one of the big shallow wooden vessels. He felt his hind feet break through something like crusted ice and sink a foot or more into a heavy, thick substance below. When he tried to lift them they only sank deeper. Then he knew what was the matter. He had stepped into a mass of hardening sugar and was a prisoner! His forefeet were free, but he dared not struggle with them for fear of getting them fast, too. The little darky, who thought the devil had stopped to rest, was huddled together in a corner not daring to move. Horatio remembered Bo sleeping safely in their camp and began to weep for his own wickedness. In the morning men would come with axes and guns. Why had he not heeded Bo? Half seated on the crusted sugar he gave himself up to sorrow and despair.

It was early morning when Bo awoke. He was surprised to see that Horatio was not beside him, for the boy was usually first awake. He called loudly. Then, as the moments passed and the Bear did not come, he grew uneasy. Suddenly a terrible suspicion flashed over him. He sprang to his feet and seizing the violin that lay beside him set forth on a run in the direction of the white sugar house. He knew Horatio would go[71] there because it was nearest, and he felt certain that something dreadful had happened. The incident of the day before made him almost sure of Horatio's errand, and he feared the worst. No doubt they had caught and killed him by this time, and what would he do now without his faithful friend?

SUDDENLY THE LITTLE FELLOW TURNED.

SUDDENLY THE LITTLE FELLOW TURNED.

He ran faster and faster. As he drew near the sugar house he heard a great commotion. For a moment he stopped. If Horatio had done something terrible and they had caught him perhaps it would be dangerous to interfere. The next moment he rushed on. Horatio was his friend and he would save his life if possible, unless——. He did not think any further, but flew on. As he dashed into the cane yard he saw crowds gathering and men running with axes and clubs. Others had guns and cane knives, and all were crowding toward the big doors of the sugar house, that were now thrown open. Inside he heard shouts, mingled with Horatio's fierce growls. His friend was still alive.

Without pausing he rushed through the doors and saw a circle of negro men gathered about the big wooden trough where the Bear was a prisoner, snapping and growling and trying to get free. The little pickaninny who, in spite of his fright, had slept all night in the corner, was there, too, and the men with axes and other weapons had entered with Bo. There was not a second to be lost.

"Wait!" screamed Bo; "wait!" And tearing through the astonished crowd he thrust the violin into Horatio's hands.

"Play!" he shouted. "Play for your worthless life!"

Horatio did not need to be told again. He reached for the violin and bow, and sitting in the now solid sugar struck the strings wildly.

Horatio fiddled furiously, while Bo shouted and sang and the crowd joined in. They all knew this song, and as they sang they forgot all else. Axes and guns and clubs were dropped as young and old fell into the swing of the music.

You could hear the noise for a mile. They danced and shouted and sang, and work was forgotten. After a long time, when they were tired out, Bo took one of the axes and carefully broke the now solid sugar away from Ratio's feet and set him free. Then they brought water and washed his hind paws and he danced for them.

After dinner, when the friends started out on their journey, the crowd followed them for nearly a mile. When all were gone Horatio turned to Bo and said:—

"I am glad you came just as you did, Bo."

"I should rather think you would be," said Bo, grimly.

"Because," continued Horatio, "if you hadn't I might have damaged some of those fellows, and I know you wouldn't have liked that, Bosephus." He looked at the little boy very humbly as he said this, expecting a severe lecture. But the little boy made no reply, and down in his heart the big Bear at that moment made a solemn and good resolve.

"Look here, Bo," he said gravely, "that sounds very pretty and may be very good poetry and true enough, but I wouldn't get to singing too much about jasmine and song birds and climbing roses if I were you, and especially girls. You are only a little boy, and besides, I can't see that there is any difference in girls, except that some are plump and some are not, and that isn't any difference to me, now," and the Bear sighed and strummed on his violin gently.

"Oh, pshaw, Ratio! There's lots of difference. Some girls are yellow and sour as a lemon, while some are as pink and sweet and blooming as a creole rose"——

"Bosephus," interrupted the Bear gravely, "you've got a touch of the swamp fever. Let me see your tongue!"

Bo stuck out his tongue.

"My tongue's all right," he grinned. "That kind of fever's in the heart."[74]

Horatio looked alarmed.

"You must take something for it right away, Bo," he declared. "I can't have you singing silly songs about jasmine and cypress and girls in milk and honey. You know we haven't seen any honey since we left Arkansaw, and I'd travel all the way back there on foot to rob one good honey tree. I'm getting tired of so much of this stuff they call sugar and cane and the like."

"Why they have honey here, Ratio, too. I haven't seen any bee trees, but I've seen plenty of bees. I suppose they are in hives—boxes that people keep for them to live in."

"Where do they have those boxes, Bo?"

"Well, in their yards mostly; generally out by the back fence."

"Could we rob them?"

"Well, I shouldn't like to try it."

The Bear walked along some distance in silence. The boy was also thinking and singing softly to himself. He was very happy. Presently he looked up and saw just ahead, in a field near the road, a tree loaded with oranges.

"Look, Ratio!" he said. "Don't you wish we had some of those?"

The Bear looked up and began to lick out his tongue.

"Climb over and get some, Bo," he said eagerly.

"Not much. I haven't forgotten the roasting ears and the watermelon we got from old man Todd in Arkansaw. We might go to the house and ask for some.

"Nonsense, Bosephus. Watch me!"

He handed Bo the fiddle, and running lightly to the hedge cleared it at a bound.

"Fine!" shouted Bo.

Horatio, without pausing, hurried over to the tree.[75]

"Funny they should leave those oranges so late," thought the little boy as he watched him.

Swinging himself to the first limb, the Bear shook off a lot of the fine yellow fruit, and climbing down, gathered in his arms all he could carry. As he did so there came a loud barking of dogs, and without looking behind him he started to run. He dropped a few of the oranges, but kept straight on, the two huge dogs that had appeared getting closer and closer. As he reached the hedge he once more made a grand leap, but the oranges prevented him doing so well as before. His foot caught in the top branches and he rolled over and over in the dusty road, the oranges flying in every direction. The dogs behind the hedge barked and raged.

Horatio rose, dusty and panting, but triumphant.

"You see, Bo," he said, "what it is to be brave. You can fill your pockets now with these delicious oranges."

He picked up one as he spoke, and brushing off the dust, bit it in half cheerfully. Then Bo, who was watching him, saw a strange thing take place. The half orange flew out of the Bear's mouth as from a popgun, and his face became so distorted that the boy thought his friend was having a spasm. Suddenly he whirled, and making a rush at the fallen oranges, began to kick them in every direction, coughing and spitting every second. The two dogs looking over the hedge stopped barking to enjoy the fun. One of the oranges rolled to Bo's feet. He picked it up and smelled it. Then rubbing it on his coat he bit into it. It was not a large bite, but it was enough. The tears rolled from his eyes and every tooth in his head jumped. Such a mixture of stinging sour and bitter he had never dreamed of. It grabbed him by the throat and shook him until his bones cracked. The top of his head seemed coming loose, and his ears fairly snapped. Then he realized what Horatio must be suffering, and laughed in spite of himself.[76]

FLEW OUT OF HIS MOUTH AS FROM A POP GUN.

FLEW OUT OF HIS MOUTH AS FROM A POP GUN.

"They are mock oranges, Ratio," he shouted, "and they are mocking us for stealing them!"

Horatio had seated himself by the roadside and was snorting and clawing at his tongue.

"I must have some honey, Bo," he said, "to take away that dreadful taste. You must find me some honey, Bo."

"You see, Ratio," said the little boy, "it doesn't pay to take things."

"Bosephus," said the Bear, "a man who will plant a tree like that so near the road deceives wilfully and should be punished."

They walked along slowly, the two dogs barking after them from behind the hedge.

Just beyond the next bend in the road a beautiful plantation came into view. They turned into the cane yard and immediately the workhands surrounded them. Horatio felt better by this time, and they began a performance. First Bo sang and then Horatio gave a gymnastic exhibition. Then at last Bo sang a closing verse as follows:—

Horatio smiled when he heard this, and the planter who was listening sent one of the servants to the house. He came out soon with a piece of fresh honey on a plate. He offered it to Horatio, who handed Bo the violin, and seizing the plate,[78] swallowed the honey at one gulp. This made the crowd shout and laugh, and then Bo shook hands with the planter and said good-bye, and all the darkies came up and wanted to shake hands, too. When he had shaken hands all around the little boy turned to look for Horatio. He was nowhere in sight. The others had not noticed him slip away.

Bo was troubled. When Horatio disappeared like that it meant mischief. He had promised reform as to pickaninnies, but Bo was never quite sure. He was about to ask the people to run in every direction in search of his comrade when there was a sudden commotion in the back door yard, and a moment later a black figure dashed through the gate with something under its arm. It was Horatio! The crowd of darkies took one look and scattered. The thing under Horatio's arm was a square, box looking affair, and out of it was streaming a black, living cloud.

"Bees!" shouted the people as they fled. "Bees! Bees!"

Bo understood instantly. The taste of honey had made Horatio greedy for more. He had gone in search of it and returned with hive and all. There was a clump of tall weeds just behind the little boy, and he dropped down into them. They hid him from view, and none too soon, for the Bear dashed past, snorting and striking at the swarm of stingers that not only covered him, but fiercely attacked everything in sight. Howls began to come from some of the hands that had failed to find shelter in time, and Bo, peeping out between the weeds, saw half a dozen darkies frantically trying to open the big door of the sugar house, which had been hastily closed by those within, while the angry bees were pelting furiously at the unfortunates.

THE BEAR DASHED PAST, SNORTING.

THE BEAR DASHED PAST, SNORTING.

As for Horatio, he was coated with bees that were trying to sting through his thick fur. He did not mind them at first, but[80] presently they began to get near his eyes. With a snarl he dropped the hive and began to paw and strike with both hands. Then they swarmed about him worse than ever, and, half blinded, he began to run around and around with no regard as to direction. Every darky in sight fled like the wind. Some of them ran out of the gate and down the road, and without seeing them, perhaps, the Bear suddenly leaped the fence and set out in the same direction. Glancing back, they saw him coming and began to shriek and scatter into the fields.

Bo waited some minutes; then, noticing that the maddened insects were no longer buzzing viciously over him, he crept out and followed. He still held the violin and was glad enough to get away from the plantation. The bees had followed the fugitive, and the boy kept far enough behind to be out of danger. By and by he met bees coming back, but perhaps they were tired or thought he belonged to another crowd, for they did not molest him. A mile further on he found Horatio sitting in the road rocking and groaning and throwing dust on himself. His eyes and nose were swollen in great knots, and his ears were each puffed up like little balloons. The bees had left him, but his sorrow was at its height.

"Hello, Ratio! Having fun all alone?" asked Bo as he came up.

"Oh, Bo, this has been an awful day!" was the wailing reply. "First those terrible oranges and then these millions and millions of murderous bees. And now I am blind, Bo, and dying. Tell me, Bo, how do I look?"

"Oh, you look all right. Your nose looks like a big potato and your ears like two little ones. I can't tell you how your eyes are, for they don't show, but your whole skin looks as if it had been stuffed full of apples and put on in a hurry."

"Bo," said Horatio meekly, "did you bring the fiddle?"[81]

HE FOUND HORATIO SITTING IN THE ROAD, ROCKING AND GROANING.

HE FOUND HORATIO SITTING IN THE ROAD, ROCKING AND GROANING.

"Well, yes; I thought it might happen that we'd need it again."

Horatio put out his paw for it. The boy gave it to him and he ran the bow gently over the strings.

"Sing, Bo," he pleaded. "Sing that song about jasmine and cypress and climbing roses. It will soothe me. Sing about girls, too, if you want to, but leave out the oranges, Bo, and put in something else besides honey in the last line."

"Ratio," said Bo, "you've got a touch of the swamp fever. Let me see your tongue!"

The little boy was singing along through the sweet Louisiana afternoon, putting into his song whatever came into his head:—

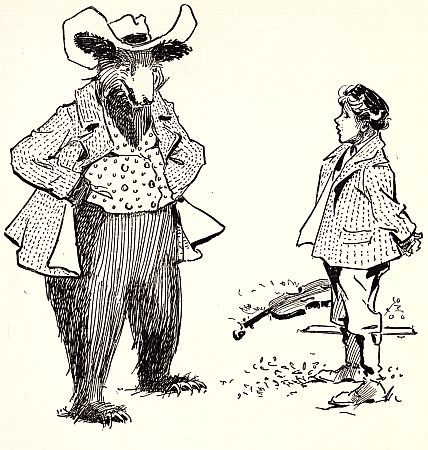

"What do you suppose is in that bundle, Bo?" asked the Bear, anxiously.

"Oh, I don't know. Old clothes, from the looks of it. The owner isn't far off.

Horatio looked in every direction. Then he walked over to the clothes.

"Why," said Bo, following; "I guess somebody's taking a swim. Come on, Ratio. Remember the honey and the oranges."

But the Bear was curious. He picked up the hat and set it on his head. Bo laughed lazily. Then Horatio laid down his[84] violin and slipped one arm into the waistcoat, trying vainly to reach with the other. Bo good-naturedly helped him. The little boy felt in the humor for fun, and Horatio looked too comical.

"Better not put on the coat," said Bo. "It might not be big enough and if you tore it the owner would make us pay for it."

But Horatio was excited.

"Hurry, Bo! Help me on with it. How do I look, Bo? I think I'll dress this way all the time, hereafter. Is my hat becoming, Bo?"

"Shed 'em!" he shouted. "Shed them clothes or I'll shoot!"

"Shed 'em!" echoed Bo. "Shed 'em, Horatio!"

The bear slipped off the coat and flung it behind him.

"Shed 'em!" shouted the man again, and the waistcoat followed.

"I won't give up the hat, Bo!" panted Horatio.

"HOW DO I LOOK, BO?"

"HOW DO I LOOK, BO?"

But Horatio was mistaken, for at that instant the world beneath his feet suddenly opened and he disappeared. Before the boy could check himself he plunged after the Bear and was struggling in the deep waters of a bayou that came to a level with the bank and was covered thickly and concealed by fallen leaves. Rising to the surface he found Horatio clinging to a fallen tree and the man, who had now overtaken them, holding[86] out a limb, which the little boy gladly seized. The hat had been already rescued.

"Well, you're a nice pair!" said their captor. "To run away with a man's clothes and then go headlong into the bayou and get his hat all wet! I'm glad you didn't have that fiddle, or you'd a-ruined it. I've bin wantin' a good fiddle a long time, an' this here looks like a good one. Come out o' that, now, an' we'll take a walk up toward the jail. I happen to be constable of this here community."

Bo groaned as he was dragged to shore. He did not mind the wetting, for the weather was warm, but now they had lost the violin and would be taken to jail. Of course they would lose all their money. Perhaps Horatio would be killed. The Bear only blinked and shook himself when he had been also towed to the bank and had scrambled out.

"I hope you won't take us to jail, sir," said Bo. "My Bear was mischievous, but he didn't mean any harm, and I have a little money I'll give you if you'll return us the violin and let us go."

"You come along with me!" answered the man, sternly. "It'll take more money than you've got to pay your fine, an' as fer that chap, we don't want no bears roamin' loose aroun' here. March on ahead there, an' don't try none o' your tricks."

The constable cocked his revolver, and boy and Bear hurriedly started in the direction of the village that showed above the trees about a mile further on.

Bo was afraid to speak to their captor again, and as he never talked with Horatio except when they were alone, they marched along disconsolately and in silence. Now and then the man strummed on the violin and chuckled to himself.

"SHED THEM CLOTHES OR I'LL SHOOT!"

"SHED THEM CLOTHES OR I'LL SHOOT!"

When they got to the village everybody came out to look at them. The man called out his story as they went along, and[88] the people laughed and jeered. Heretofore the friends had entered Louisiana villages in triumph. Now, for the first time, they came dishonored and disgraced. Poor Horatio looked very downcast. He knew that he was to blame for it all.

When they got to the court room they found that the Justice of the Peace was away fishing, so they were lodged in jail for the night. It was only a little one room affair, with two small iron-barred windows, quite high from the ground. Boys climbed up and looked through these windows and threw stones and coal in at Horatio, who huddled in a corner. By and by the officer came with a plate of supper for Bo. He drove the boys away and left the friends together. There was no supper for the Bear, so the little boy divided with him.

"Bo," said Horatio, tearfully, "it was my fault. They'll let you go, and, and—I hope they'll give you my skin, Bo."

Then they went to sleep.

Early next morning there was a crowd around the jail. The Justice had returned and the people wanted to see the fun. The friends were hustled into court by the constable, the crowd stepping back to let Horatio pass. The justice was rather a young man and had a good-natured face, which made Bo more hopeful. But when they heard the constable make his charge against them, both lost heart. They were accused of stealing and damages and a lot of other things that they could not understand. The Justice listened and then turned to the prisoners.

"What have you to say for yourselves?" he asked, looking straight at Bo. At first the little boy tried to speak and could not. The court room was still—every one waiting to hear what he was about to say. All at once an idea came to him.

"Please, sir," he trembled, "if you will let my Bear have the violin we will plead our case together."[89]

"What violin? What does the boy mean?" asked the Justice, turning to the constable.

"Oh, an ole fiddle they dropped when they took my clothes. I lef' it down 't the house this morning."

Bo's heart sank. It was their only chance. He was about to give up when suddenly there came another gleam of hope, though very faint. Wheeling quickly toward the sorrow stricken Bear he shouted:—

"Perform for them, Horatio! Perform!"

The words acted on Horatio like a shock of electricity. He straightened up with a snort that caused the crowd to fall back, knocking each other over like dominos. Then he made a bound into the open space and stood on his head. Then with a spring backward he landed on his feet, and waved a bow to the Justice! Another bound and he was walking on his hands and then, after another bow to the Court, he turned a series of somersaults so rapidly that he looked like a great wheel! When he landed on his feet this time, and bowed once more to the Court, the crowd broke out into a mighty cheer of applause.

"Order!" shouted the Justice. "Order!"

It grew still, and the little boy looked at the Court anxiously.

"Please, Your Honor," he said humbly, "that's our case."

"Case!" roared the Justice. "Well, I should say that was a case of fits and revolution."

At this the crowd cheered again until they were rapped to order by the Court.

"I sentence you," he said solemnly, and looking sternly at Horatio, "to sudden and disagreeable death!"

He paused, and Horatio staggered against Bo, who was very pale.

A CASE OF FITS AND REVOLUTION.

A CASE OF FITS AND REVOLUTION.

"To sudden death," continued the Court, "if I catch you[91] running off and falling in the water with any more of my officer's clothes. And I now fine you, for the first offense, a performance on the common for the whole town! Court is adjourned! Show begins at once! Constable, bring that fiddle!"

With a wild shout the people poured outside. Many scrambled over each other to get near Bosephus and the wonderful Bear, and when the violin was brought and the show had begun every soul in the village was gathered on the common.

That night, when all was over, the little boy and the Bear were the guests of the Justice, who owned a fine plantation adjoining the village. During the evening he had a long talk with Bo, and seemed greatly impressed with the little boy's natural ability and shrewdness. When they parted next morning he said:—

"Remember, if you ever feel like giving up travel, come back here and I'll send you to school and college and make a man of you."

"I'll remember," said Bo, as they shook hands. A crowd had gathered to see the travellers off. The constable was among them, and as they disappeared around a bend in the road he waved and shouted with the rest.

"Bosephus," said Horatio gravely, "I hope you don't think of deserting me. Remember how many close places I have helped you out of. This last was a little the closest of all, Bosephus, and I shudder to think where you might have been today if it had not been for me."

"That's so," said the little boy solemnly. "I don't suppose they'd have even given me your skin, Ratio."

"Bo," said he presently, "I shouldn't wonder if that singing of yours scared the fish all away."

"I wouldn't say that to you, Ratio. I know if you'd wake up and take the fiddle and play some they'd walk right out on the bank."

The Bear laughed sleepily. He was in a comfortable position and the warm afternoon sun was soothing. He hummed some negro lines he had heard:—

"I shouldn't wonder if you were right, Ratio," assented Bo, anxiously. "It does look better over there, only there's no way[93] to get across except this slippery looking, rotten old log, and I don't feel much like trying that."

"Walk out on it a little way, Bo," said Horatio, getting interested, "and throw your line over there by that cypress snag. That looks like a good place."

Bosephus rose cautiously, and, balancing himself with the long cane pole, edged his way a few inches at a time toward the middle of the stream, pausing every little way to be sure that the log showed no sign of yielding. He could swim, but he did not wish for a wetting, and besides there were a good many alligators in these Louisiana waters and some very fierce snapping turtles. He had heard the negroes say that alligators were particularly fond of boys, and that snapping turtles never let go till it thundered. He had no wish to furnish supper for an alligator and there were no signs of a thunder storm. Hence he advanced with great prudence. When he had nearly reached the centre Horatio called to him.

"Try it from there, Bo! Your line's long enough to reach!"

The little boy steadied himself by a limb that projected from the log and swung his line in the direction the Bear had indicated. Then he waited, holding his breath almost, and watching his float, which lay silently on the water. Horatio was watching, too, with half closed eyes, and now and then giving instructions.

"Pull it a little more to the right, Bo—nearer that root," he whispered.

Bosephus obeyed, but the float still lay silently on the water.

"Draw it a little toward you, Bo; sometimes when they think its going away they make a rush for it."

Again the little boy did as directed, but without result.[94]

"Lift out your bait and see if it's all right. Now fling it a little further toward the bank."

Bo lifted out the bait, which was still lively and untouched, and flung it far over toward the other shore. Then he waited in silence once more, but there was no sign of even so much as a nibble.

"Oh, pshaw, Ratio!" he said at last impatiently. "I don't believe you know anything about fishing. Either that or there are no fish in here—one of the two."

He had turned his head toward the Bear as he spoke and was not looking at his float. All at once the Bear sat straight up, pointing at the water.

"Your cork's gone!" he shouted. "You've got one! Pull, Bo, pull!"

The little boy turned so quickly that he almost lost his balance and could not immediately obey. Horatio was wild with excitement.

"Why don't you pull?" he howled. "Do you expect him to climb up your pole? Are you waiting for him to make his toilet before he appears? Well, talk about fishermen!"

Bosephus was struggling madly to follow instructions. He was holding to the dead limb like grim death and pulling fiercely at the pole with one hand. The fish must be a large one, for it swung furiously from side to side, but could not be brought to the surface. Horatio on the bank was still shouting and dancing violently.

"You'll lose him!" he yelled; "you'll never in the world land him that way. You ought to go fishing for tin fish in a tub! Just let me out there; I'll show you how to fish!" and Horatio made a rush toward the log on which Bo was standing.

"PULL, BO, PULL!"

"PULL, BO, PULL!"

"Go back! Go back!" screamed the little boy. "It won't hold us both!" But the Bear was too much excited by this time[96] to heed any caution. He hurried to the centre of the log and seizing the pole from Bo's hand gave a fierce pull. The fish swung clear of the water and far out on the bank, but the strain on their support was too great. There was a loud cracking sound, and before they knew what had happened both were struggling in the water.

"Help! Help!" howled Horatio. "I'm drowning!"

"Hold to the end of the log!" shouted Bo. "I'll swim ashore and tow you in with the pole!"

He struck out as he spoke and in a few strokes was near enough to seize some bushes that overhung the water. Suddenly he heard Horatio give forth a scream so wild that he whirled about to look. Then he saw something that made him turn cold. In a half circle, a few feet away from where Horatio was clinging to the end of the broken log for dear life, there had risen from the water a number of long, black, ugly heads. A drove of alligators!

"Bo! Bo!" shrieked the wretched Bear. "They're after me! They'll eat me alive—skin and all! Save me! Save me!"

The little boy swung himself to the shore and dashed up the bank. His first thought had been to seize the fishing pole and with it to drag Horatio to safety. But at that instant his eye fell on the violin. He had learned to play very well himself during the last few weeks and he remembered the night of the panther dance in the Arkansaw woods. He snatched up the instrument and struck the bow across the strings.

"Sing, Horatio!" he shouted. "It's your turn to sing!" and Bosephus broke out into a song that after the first line the Bear joined as if he never expected to sing again on earth.