CHAPTER XX.

EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY.

Books Recommended: Anderson, Architecture of the Renaissance in Italy. Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance; Geschichte der Renaissance in Italien; Der Cicerone. Cellesi, Sei Fabbriche di Firenze. Cicognara, Le Fabbriche più cospicue di Venezia. Durm, Die Baukunst der Renaissance in Italien (in Hdbuch. d. Arch.). Fergusson, History of Modern Architecture. Geymüller, La Renaissance en Toscane. Montigny et Famin, Architecture Toscane. Moore, Character of Renaissance Architecture. Müntz, La Renaissance en Italie et en France à l’époque de Charles VIII. Palustre, L’Architecture de la Renaissance. Pater, Studies in the Renaissance. Symonds, The Renaissance of the Fine Arts in Italy. Tosi and Becchio, Altars, Tabernacles, and Tombs.

THE CLASSIC REVIVAL. The abandonment of Gothic architecture in Italy and the substitution in its place of forms derived from classic models were occasioned by no sudden or merely local revolution. The Renaissance was the result of a profound and universal intellectual movement, whose roots may be traced far back into the Middle Ages, and which manifested itself first in Italy simply because there the conditions were most propitious. It spread through Europe just as rapidly as similar conditions appearing in other countries prepared the way for it. The essence of this far-reaching movement was the protest of the individual reason against the trammels of external and arbitrary authority—a protest which found its earliest organized expression in the Humanists. In its assertion of the intellectual and moral rights of the individual, the Renaissance laid the foundations of modern civilization. The same spirit, in rejecting the authority and teachings of the 271 Church in matters of purely secular knowledge, led to the questionings of the precursors of modern science and the discoveries of the early navigators. But in nothing did the reaction against mediæval scholasticism and asceticism display itself more strikingly than in the joyful enthusiasm which marked the pursuit of classic studies. The long-neglected treasures of classic literature were reopened, almost rediscovered, in the fourteenth century by the immortal trio—Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. The joy of living, the hitherto forbidden delight in beauty and pleasure for their own sakes, the exultant awakening to the sense of personal freedom, which came with the bursting of mediæval fetters, found in classic art and literature their most sympathetic expression. It was in Italy, where feudalism had never fully established itself, and where the municipalities and guilds had developed, as nowhere else, the sense of civic and personal freedom, that these symptoms first manifested themselves. In Italy, and above all in the Tuscan cities, they appeared throughout the fourteenth century in the growing enthusiasm for all that recalled the antique culture, and in the rapid advance of luxury and refinement in both public and private life.

THE RENAISSANCE OF THE ARTS. Classic Roman architecture had never lost its influence on the Italian taste. Gothic art, already declining in the West, had never been in Italy more than a borrowed garb, clothing architectural conceptions classic rather than Gothic in spirit. The antique monuments which abounded on every hand were ever present models for the artist, and to the Florentines of the early fifteenth century the civilization which had created them represented the highest ideal of human culture. They longed to revive in their own time the glories of ancient Rome, and appropriated with uncritical and undiscriminating enthusiasm the good and the bad, the early and the late forms of Roman art, Naïvely unconscious of the disparity 272 between their own architectural conceptions and those they fancied they imitated, they were, unknown to themselves, creating a new style, in which the details of Roman art were fitted in novel combinations to new requirements. In proportion as the Church lost its hold on the culture of the age, this new architecture entered increasingly into the service of private luxury and public display. It created, it is true, striking types of church design, and made of the dome one of the most imposing of external features; but its most characteristic products were palaces, villas, council halls, and monuments to the great and the powerful. The personal element in design asserted itself as never before in the growth of schools and the development of styles. Thenceforward the history of Italian architecture becomes the history of the achievements of individual artists.

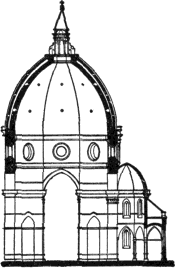

EARLY BEGINNINGS. Already in the 13th century the pulpits of Niccolo Pisano at Sienna and Pisa had revealed that master’s direct recourse to antique monuments for inspiration and suggestion. In the frescoes of Giotto and his followers, and in the architectural details of many nominally Gothic buildings, classic forms had appeared with increasing frequency during the fourteenth century. This was especially true in Florence, which was then the artistic capital of Italy. Never, perhaps, since the days of Pericles, had there been another community so permeated with the love of beauty in art, and so endowed with the capacity to realize it. Nowhere else in Europe at that time was there such strenuous life, such intense feeling, or such free course for individual genius as in Florence. Her artists, with unexampled versatility, addressed themselves with equal success to goldsmiths’ work, sculpture, architecture and engineering—often to painting and poetry as well; and they were quick to catch in their art the spirit of the classic revival. The new movement achieved its first architectural 273 triumph in the dome of the cathedral of Florence (1420–64); and it was Florentine—or at least Tuscan—artists who planted in other centres the seeds of the new art that were to spring up in the local and provincial schools of Sienna, Milan, Pavia, Bologna, and Venice, of Brescia, Lucca, Perugia, and Rimini, and many other North Italian cities. The movement asserted itself late in Rome and Naples, as an importation from Northern Italy, but it bore abundant fruit in these cities in its later stages.

PERIODS. The classic styles which grew up out of the Renaissance may be divided for convenience into four periods.

The Early Renaissance or Formative Period, 1420–90; characterized by the grace and freedom of the decorative detail, suggested by Roman prototypes and applied to compositions of great variety and originality.

The High Renaissance or Formally Classic Period, 1490–1550. During this period classic details were copied with increasing fidelity, the orders especially appearing in almost all compositions; decoration meanwhile losing somewhat in grace and freedom.

The Early Baroque (or Baroco), 1550–1600; a period of classic formality characterized by the use of colossal orders, engaged columns and rather scanty decoration.

The Decline or Later Baroque, marked by poverty of invention in the composition and a predominance of vulgar sham and display in the decoration. Broken pediments, huge scrolls, florid stucco-work and a general disregard of architectural propriety were universal.

During the eighteenth century there was a reaction from these extravagances, which showed itself in a return to the servile copying of classic models, sometimes not without a certain dignity of composition and restraint in the decoration.

By many writers the name Renaissance is confined to the 274 first period. This is correct from the etymological point of view; but it is impossible to dissociate the first period historically from those which followed it, down to the final exhaustion of the artistic movement to which it gave birth, in the heavy extravagances of the Rococo.

Another division is made by the Italians, who give the name of the Quattrocento to the period which closed with the end of the fifteenth century, Cinquecento to the sixteenth century, and Seicento to the seventeenth century or Rococo. It has, however, become common to confine the use of the term Cinquecento to the first half of the sixteenth century.

FIG. 158.—EARLY RENAISSANCE CAPITAL, PAL. ZORZI, VENICE.

CONSTRUCTION AND DETAIL. The architects of the Renaissance occupied themselves more with form than with construction, and rarely set themselves constructive problems of great difficulty. Although the new architecture began with the colossal dome of the cathedral of Florence, and culminated in the stupendous church of St. Peter at Rome, it was pre-eminently an architecture of palaces and villas, of façades and of decorative display. Constructive difficulties were reduced to their lowest terms, and the constructive framework was concealed, not emphasized, by the decorative apparel of the design. Among the masterpieces of the early Renaissance are many buildings of small dimensions, such as gates, chapels, tombs and fountains. In these the individual fancy had full sway, and produced surprising results by the beauty of enriched mouldings, of carved friezes with infant genii, wreaths of fruit, griffins, masks and scrolls; by pilasters covered with arabesques as delicate in modelling as if wrought in silver; by inlays of marble, panels of glazed terra-cotta, marvellously carved doors, fine stucco-work in relief, capitals and cornices of wonderful richness and variety. The Roman orders appeared only in free imitations, with panelled and carved pilasters for the most part instead of columns, and capitals 275 of fanciful design, recalling remotely the Corinthian by their volutes and leaves (Fig. 158). Instead of the low-pitched classic pediments, there appears frequently an arched cornice enclosing a sculptured lunette. Doors and windows were enclosed in richly carved frames, sometimes arched and sometimes square. Façades were flat and unbroken, depending mainly for effect upon the distribution and adornment of the openings, and the design of doorways, courtyards and cornices. Internally vaults and flat ceilings of wood and plaster were about equally common, the barrel vault and dome occurring far more frequently than the groined vault. Many of the ceilings of this period are of remarkable richness and beauty.

FIG. 159.—SECTION OF DOME OF DUOMO,

FLORENCE.

THE EARLY RENAISSANCE IN FLORENCE: THE DUOMO. In the year 1417 a public competition was held for completing the cathedral of Florence by a dome over the immense octagon, 143 feet in diameter. Filippo Brunelleschi, sculptor and architect (1377–1446), who with Donatello had journeyed to Rome to study there the masterworks of ancient art, after demonstrating the inadequacy of all the solutions proposed by the competitors, was finally permitted to undertake the gigantic task according to his own plans. These provided for an octagonal dome in two shells, connected 276 by eight major and sixteen minor ribs, and crowned by a lantern at the top (Fig. 159). This wholly original conception, by which for the first time (outside of Moslem art) the dome was made an external feature fitly terminating in the light forms and upward movement of a lantern, was carried out between the years 1420 and 1464. Though in no wise an imitation of Roman forms, it was classic in its spirit, in its vastness and its simplicity of line, and was made possible solely by Brunelleschi’s studies of Roman design and construction (Fig. 160).

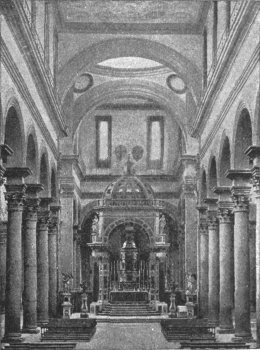

OTHER CHURCHES. From Brunelleschi’s designs were also erected the Pazzi Chapel in Sta. Croce, a charming design of a Greek cross covered with a dome at the intersection, and preceded by a vestibule with a richly decorated vault; and the two great churches of S. Lorenzo (1425) and S. Spirito (1433–1476, Fig. 161). Both reproduced in a measure the plan of the Pisa Cathedral, having a three-aisled nave and transepts, with a low dome over the crossing. The side aisles were covered with domical vaults and the central aisles with flat wooden or plaster ceilings. All the details of columns, arches and mouldings were imitated from Roman models, and yet the result was something entirely new. Consciously or unconsciously, Brunelleschi was reviving Byzantine rather than Roman conceptions in the planning and structural design of these domical churches, but the garb in which he clothed them was Roman, at least in detail. The Old Sacristy of S. Lorenzo was another domical design of great beauty.

277

FIG. 160.—EXTERIOR OF DOME OF DUOMO,

FLORENCE.

From this time on the new style was in general use for church designs. L. B. Alberti (1404–73), who had in Rome mastered classic details more thoroughly than Brunelleschi, remodelled the church of S. Francesco at Rimini with Roman pilasters and arches, and with engaged orders in the façade, which, however, was never completed. His great work was the church of S. Andrea at Mantua, a Latin cross in plan, with a dome at the intersection (the present high dome dating however, only from the 18th century) and a façade to which the conception of a Roman triumphal arch was skilfully adapted. His façade of incrusted marbles for the church of S. M. Novella at Florence was a less successful work, though its flaring consoles over the side aisles established an unfortunate precedent frequently imitated in later churches.

A great activity in church-building marked the period between 1475 and 1490. The plans of the churches erected about this time throughout north Italy display an interesting variety of arrangements, in nearly all of which the dome is combined with the three-aisled cruciform plan, either as a central feature at the crossing or as a domical vault over each bay. Bologna and Ferrara possess a number of churches of this kind. Occasionally the basilican arrangement was followed, with columnar arcades separating 278 the aisles. More often, however, the pier-arches were of the Roman type, with engaged columns or pilasters between them. The interiors, presumably intended to receive painted decorations, were in most cases somewhat bare of ornament, pleasing rather by happy proportions and effective vaulting or rich flat ceilings, panelled, painted and gilded, than by elaborate architectural detail. A similar scantiness of ornament is to be remarked in the exteriors, excepting the façades, which were sometimes highly ornate; the doorways, with columns, pediments, sculpture and carving, receiving especial attention. High external domes did not come into general use until the next period. In Milan, Pavia, and some other Lombard cities, the internal cupola over the crossing was, however, covered externally by a lofty structure in diminishing stages, like that of the Certosa at Pavia (Fig. 152), or that erected by Bramante for the church of S. M. delle Grazie at Milan. At Prato, in the church of the Madonna delle Carceri (1495–1516), by Giuliano da S. Gallo, the type of the Pazzi chapel reappears in a larger scale; the plan is cruciform, with equal or nearly equal arms covered by barrel vaults, at whose intersection rises a dome of 279 moderate height on pendentives. This charming edifice, with its unfinished exterior of white marble, its simple and dignified lines, and internal embellishments in della-Robbia ware, is one of the masterpieces of the period.

FIG. 161.—INTERIOR OF S. SPIRITO, FLORENCE.

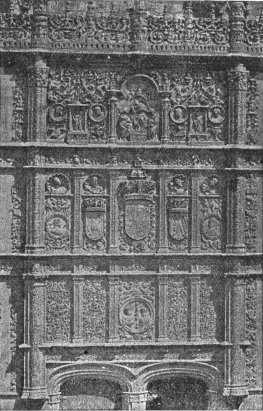

In the designing of chapels and oratories the architects of the early Renaissance attained conspicuous success, these edifices presenting fewer structural limitations and being more purely decorative in character than the larger churches. Such façades as that of S. Bernardino at Perugia and of the Frati di S. Spirito at Bologna are among the most delightful products of the decorative fancy of the 15th century.

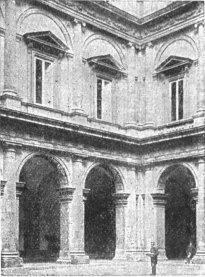

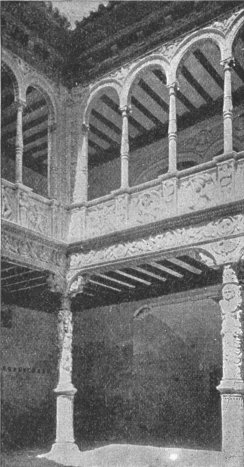

FIG. 162.—COURTYARD OF RICCARDI PALACE, FLORENCE.

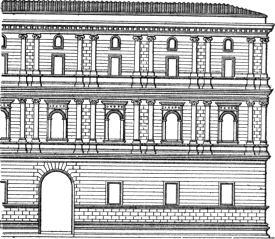

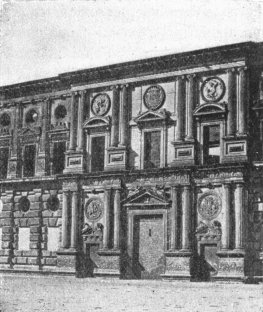

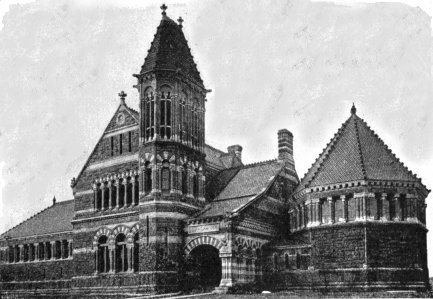

FLORENTINE PALACES. While the architects of this period failed to develop any new and thoroughly satisfactory ecclesiastical type, they attained conspicuous success in palace-architecture. The Riccardi palace in Florence (1430) marks the first step of the Renaissance in this direction. It was built for the great Cosimo di Medici by Michelozzi (1397–1473), a contemporary of Brunelleschi and Alberti, and a man of great talent. Its imposing rectangular façade, with widely spaced mullioned windows in two stories over a massive basement, is crowned with a classic cornice of unusual and perhaps excessive size. In 280 spite of the bold and fortress-like character of the rusticated masonry of these façades, and the mediæval look they seem to present to modern eyes, they marked a revolution in style and established a type frequently imitated in later years. The courtyard, in contrast with this stern exterior, appears light and cheerful (Fig. 162). Its wall is carried on round arches borne by columns with Corinthianesque capitals, and the arcade is enriched with sculptured medallions. The Pitti Palace, by Brunelleschi (1435), embodies the same ideas on a more colossal scale, but lacks the grace of an adequate cornice. A lighter and more ornate style appeared in 1460 in the P. Rucellai, by Alberti, in which for the first time classical pilasters in superposed stages were applied to a street façade. To avoid the dilemma of either insufficiently crowning the edifice or making the cornice too heavy for the upper range of pilasters, Alberti made use of brackets, occupying the width of the upper frieze, and converting the whole upper entablature into a cornice. But this compromise was not quite successful, and it remained for later architects in Venice, Verona, and Rome to work out more satisfactory methods of applying the orders to many-storied palace façades. In the great P. Strozzi (Fig. 163), erected in 1490 by Benedetto da Majano and Cronaca, the architects reverted to the earlier type of the P. Riccardi, treating it with greater refinement and producing one of the noblest palaces of Italy.

FIG. 163.—FAÇADE OF STROZZI PALACE, FLORENCE.

COURTYARDS; ARCADES. These palaces were all built around interior courts, whose walls rested on columnar arcades, as in the P. Riccardi (Fig. 162). The origin of these arcades may be found in the arcaded cloisters of mediæval monastic churches, which often suggest classic models, as in those of St. Paul-beyond-the-Walls and St. John Lateran at Rome. Brunelleschi not only introduced columnar arcades into a number of cloisters and palace courts, but also used them effectively as exterior features in the Loggia S. Paolo and the Foundling Hospital (Ospedale degli Innocenti) at Florence. The chief drawback in these light arcades was their inability to withstand the thrust of the vaulting over the space behind them, and the consequent recourse to iron tie-rods where vaulting was used. The Italians, however, seemed to care little about this disfigurement.

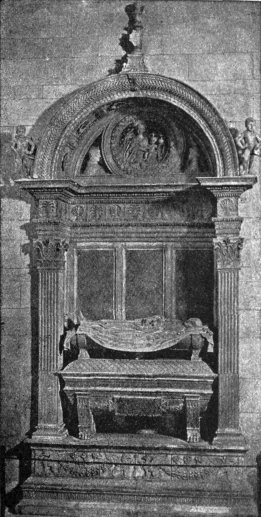

MINOR WORKS. The details of the new style were developed quite as rapidly in purely decorative works as in monumental buildings. Altars, mural monuments, tabernacles, pulpits and ciboria afforded scope for the genius of the most distinguished artists. Among those who were specially celebrated in works of this kind should be named Lucca della Robbia (1400–82) and his successors, Mino da Fiesole (1431–84) and Benedetto da Majano (1442–97). Possessed of a wonderful fertility of invention, they and their pupils multiplied their works in extraordinary number and variety, not only throughout north Italy, but also in Rome and Naples. Among the most famous examples of this branch of design may be mentioned a pulpit in Sta. Croce by B. da Majano; a terra-cotta fountain in the sacristy of S. M. Novella, by the della Robbias; the Marsupini tomb in Sta. Croce, by Desiderio da Settignano (all in Florence); the della Rovere tomb in S. M. del Popolo, Rome, by Mino da Fiesole, and in the Cathedral at Lucca the Noceto tomb and the Tempietto, by Matteo Civitali. It was in 282 works of this character that the Renaissance oftenest made its first appearance in a new centre, as was the case in Sienna, Pisa, Lucca, Naples, etc.

FIG. 164.—TOMB OF PIETRO DI NOCETO, LUCCA.

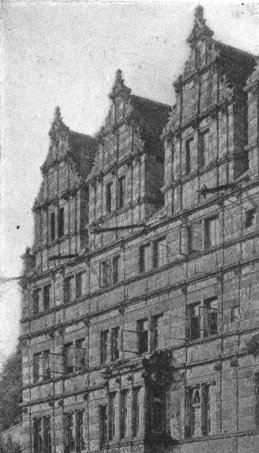

NORTH ITALY. Between 1450 and 1490 the Renaissance presented in Sienna, in a number of important palaces, a sharp contrast to the prevalent Gothic style of that city. The P. Piccolomini—a somewhat crude imitation of the P. Riccardi in Florence—dates from 1463; the P. del Governo was built 1469, and the Spannocchi Palace in 1470. In 1463 Ant. Federighi built there the Loggia del Papa. About the same time Bernardo di Lorenzo was building for Pope Pius II. (Æneas Sylvius Piccolomini) an entirely new city, Pienza, with a cathedral, archbishop’s palace, town hall and Papal residence (the P. Piccolomini), which are interesting if not strikingly original works. Pisa possesses few early Renaissance structures, owing to the utter prostration of her fortunes 283 in the 15th century, and the dominance of Pisan Gothic traditions. In Lucca, besides a wealth of minor monuments (largely the work of Matteo Civitali, 1435–1501) in various churches, a number of palaces date from this period, the most important being the P. Pretorio and P. Bernardini. To Milan the Renaissance was carried by the Florentine masters Michelozzi and Filarete, to whom are respectively due the Portinari Chapel in S. Eustorgio (1462) and the earlier part of the great Ospedale Maggiore (1457). In the latter, an edifice of brick with terra-cotta enrichments, the windows were Gothic in outline—an unusual mixture of styles, even in Italy. The munificence of the Sforzas, the hereditary tyrants of the province, embellished the semi-Gothic Certosa of Pavia with a new marble façade, begun 1476 or 1491, which in its fanciful and exuberant decoration, and the small scale of its parts, belongs properly to the early Renaissance. Exquisitely beautiful in detail, it resembles rather a magnified altar-piece than a work of architecture, properly speaking. Bologna and Ferrara developed somewhat late in the century a strong local school of architecture, remarkable especially for the beauty of its courtyards, its graceful street arcades, and its artistic treatment of brick and terra-cotta (P. Bevilacqua, P. Fava, at Bologna; P. Scrofa, P. Roverella, at Ferrara). About the same time palaces with interior arcades and details in the new style were erected in Verona, Vicenza, Mantua, and other cities.

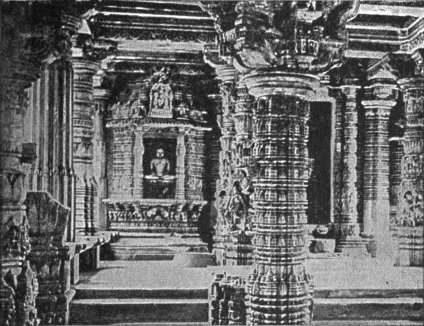

VENICE. In this city of merchant princes and a wealthy bourgeoisie, the architecture of the Renaissance took on a new aspect of splendor and display. It was late in appearing, the Gothic style with its tinge of Byzantine decorative traditions having here developed into a style well suited to the needs of a rich and relatively tranquil community. These traditions the architects of the new style appropriated in a measure, as in the marble incrustations of the exquisite little church of S. M. dei Miracoli (1480–89), and the façade 284 of the Scuola di S. Marco (1485–1533), both by Pietro Lombardo. Nowhere else, unless on the contemporary façade of the Certosa at Pavia, were marble inlays and delicate carving, combined with a framework of thin pilasters, finely profiled entablatures and arched pediments, so lavishly bestowed upon the street fronts of churches and palaces. The family of the Lombardi (Martino, his sons Moro and Pietro, and grandsons Antonio and Tullio), with Ant. Bregno and Bart. Buon, were the leaders in the architectural Renaissance of this period, and to them Venice owes her choicest masterpieces in the new style. Its first appearance is noted in the later portions of the church of S. Zaccaria (1456–1515), partly Gothic internally, with a façade whose semicircular pediment and small decorative arcades show a somewhat timid but interesting application of classic details. In this church, and still more so in S. Giobbe (1451–93) and the Miracoli above mentioned, the decorative element predominates throughout. It is hard to imagine details more graceful in design, more effective in the swing of their movement, or more delicate in execution than the mouldings, reliefs, wreaths, scrolls, and capitals one encounters in these buildings. Yet in structural interest, in scale and breadth of planning, these early Renaissance Venetian buildings hold a relatively inferior rank.

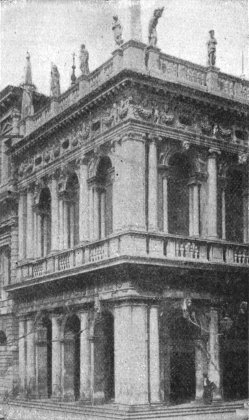

FIG. 165.—VENDRAMINI PALACE, VENICE.

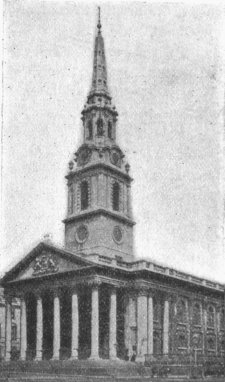

PALACES. The great Court of the Doge’s Palace, begun 1483 by Ant. Rizzio, belongs only in part to the first period. It shows, however, the lack of constructive principle and of largeness of composition just mentioned, but its decorative effect and picturesque variety elicit almost universal admiration. Like the neighboring façade of St. Mark’s, it violates nearly every principle of correct composition, and yet in a measure atones for this capital defect by its charm of detail. Far more satisfactory from the purely architectural point of view is the façade of the P. Vendramini (Vendramin-Calergi), by Pietro Lombardo (1481). The simple, 285 stately lines of its composition, the dignity of its broad arched and mullioned windows, separated by engaged columns—the earliest example in Venice of this feature, and one of the earliest in Italy—its well-proportioned basement and upper stories, crowned by an adequate but somewhat heavy entablature, make this one of the finest palaces in Italy (Fig. 165) It established a type of large-windowed, vigorously modelled façades which later architects developed, but hardly surpassed. In the smaller contemporary, P. Dario, another type appears, better suited for small buildings, depending for effect mainly upon well-ordered openings and incrusted panelling of colored marble.

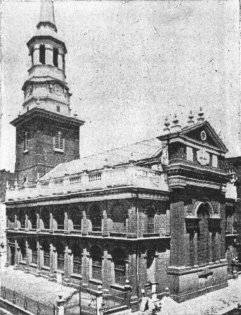

ROME. Internal disorders and the long exile of the popes had by the end of the fourteenth century reduced Rome to utter insignificance. Not until the second half of the fifteenth century did returning prosperity and wealth afford 286 the Renaissance its opportunity in the Eternal City. Pope Nicholas V. had, indeed, begun the rebuilding of St. Peter’s from designs by B. Rossellini, in 1450, but the project lapsed shortly after with the death of the pope. The earliest Renaissance building in Rome was the P. di Venezia, begun in 1455, together with the adjoining porch of S. Marco. In this palace and the adjoining unfinished Palazzetto we find the influence of the old Roman monuments clearly manifested in the court arcades, built like those of the Colosseum, with superposed stages of massive piers and engaged columns carrying entablatures. The proportions are awkward, the details coarse; but the spirit of Roman classicism is here seen in the germ. The exterior of this palace is, however, still Gothic in spirit. The architects are unknown; Giuliano da Majano (1452–90), Giacomo di Pietrasanta, and Meo del Caprino (1430–1501) are known to have worked upon it, but it is not certain in what capacity.

The new style, reaching, and in time overcoming, the conservatism of the Church, overthrew the old basilican traditions. In S. Agostino (1479–83), by Pietrasanta, and S. M. del Popolo, by Pintelli (?), piers with pilasters or half-columns and massive arches separate the aisles, and the crossing is crowned with a dome. To the same period belong the Sistine chapel and parts of the Vatican palace, but the interest of these lies rather in their later decorations than in their somewhat scanty architectural merit.

The architectural renewal of Rome, thus begun, reached its culmination in the following period.

OTHER MONUMENTS. The complete enumeration of even the most important Early Renaissance monuments of Italy is impossible within our limits. Two or three only can here be singled out as suggesting types. Among town halls of this period the first place belongs to the P. del Consiglio at Verona, by Fra Giocondo (1435–1515). In this beautiful edifice the façade consists of a light and graceful 287 arcade supporting a wall pierced with four windows, and covered with elaborate frescoed arabesques (recently restored). Its unfortunate division by pilasters into four bays, with a pier in the centre, is a blemish avoided in the contemporary P. del Consiglio at Padua. The Ducal Palace at Urbino, by Luciano da Laurano (1468), is noteworthy for its fine arcaded court, and was highly famed in its day. At Brescia S. M. dei Miracoli is a remarkable example of a cruciform domical church dating from the close of this period, and is especially celebrated for the exuberant decoration of its porch and its elaborate detail. Few campaniles were built in this period; the best of them are at Venice. Naples possesses several interesting Early Renaissance monuments, chief among which are the Porta Capuana (1484), by Giul. da Majano, the triumphal Arch of Alphonso of Arragon, by Pietro di Martino, and the P. Gravina, by Gab. d’Agnolo. Naples is also very rich in minor works of the early Renaissance, in which it ranks with Florence, Venice, and Rome.

288CHAPTER XXI.

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued.

THE ADVANCED RENAISSANCE AND DECLINE.

Books Recommended: As before, Burckhardt, Cicognara, Fergusson, Palustre. Also, Gauthier, Les plus beaux edifices de Gênes. Geymüller, Les projets primitifs pour la basilique de St. Pierre de Rome. Gurlitt, Geschichte des Barockstiles in Italien. Letarouilly, Édifices de Rome Moderne; Le Vatican. Palladio, The Works of A. Palladio.

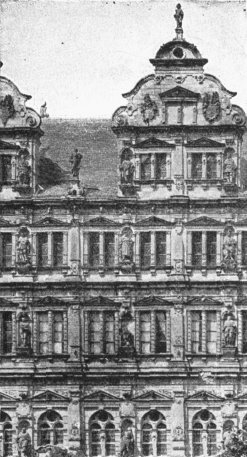

CHARACTER OF THE ADVANCED RENAISSANCE. It was inevitable that the study and imitation of Roman architecture should lead to an increasingly literal rendering of classic details and a closer copying of antique compositions. Toward the close of the fifteenth century the symptoms began to multiply of the approaching reign of formal classicism. Correctness in the reproduction of old Roman forms came in time to be esteemed as one of the chief of architectural virtues, and in the following period the orders became the principal resource of the architect. During the so-called Cinquecento, that is, from the close of the fifteenth century to nearly or quite 1550, architecture still retained much of the freedom and refinement of the Quattrocento. There was meanwhile a notable advance in dignity and amplitude of design, especially in the internal distribution of buildings. Externally the orders were freely used as subordinate features in the decoration of doors and windows, and in court arcades of the Roman type. The lantern-crowned 289 dome upon a high drum was developed into one of the noblest of architectural forms. Great attention was bestowed upon all subordinate features; doors and windows were treated with frames and pediments of extreme elegance and refinement; all the cornices and mouldings were proportioned and profiled with the utmost care, and the balustrade was elaborated into a feature at once useful and highly ornate. Interior decoration was even more splendid than before, if somewhat less delicate and subtle; relief enrichments in stucco were used with admirable effect, and the greatest artists exercised their talents in the painting of vaults and ceilings, as in P. del Té at Mantua, by Giulio Romano (1492–1546), and the Sistine Chapel at Rome, by Michael Angelo. This period is distinguished by an exceptional number of great architects and buildings. It was ushered in by Bramante Lazzari, of Urbino (1444–1514), and closed during the career of Michael Angelo Buonarotti (1475–1564); two names worthy to rank with that of Brunelleschi. Inferior only to these in architectural genius were Raphael (1483–1520), Baldassare Peruzzi (1481–1536), Antonio da San Gallo the Younger (1485–1546), and G. Barozzi da Vignola (1507–1572), in Rome; Giacopo Tatti Sansovino (1479–1570), in Venice, and others almost equally illustrious. This period witnessed the erection of an extraordinary series of palaces, villas, and churches, the beginning and much of the construction of St. Peter’s at Rome, and a complete transformation in the aspect of that city.

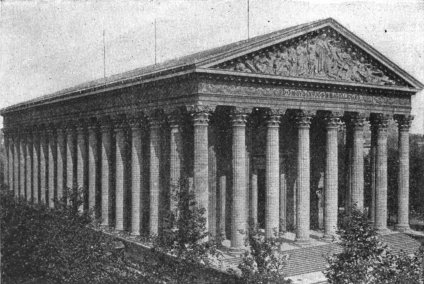

FIG. 166.—FAÇADE OF THE GIRAUD PALACE, ROME.

BRAMANTE’S WORKS. While precise time limits cannot be set to architectural styles, it is not irrational to date this period from the maturing of Bramante’s genius. While his earlier works in Milan belong to the Quattrocento (S. M. delle Grazie, the sacristy of San Satiro, the extension of the Great Hospital), his later designs show the classic tendency very clearly. The charming Tempietto in the court of 290 S. Pietro in Montorio at Rome, a circular temple-like chapel (1502), is composed of purely classic elements. In the P. Giraud (Fig. 166) and the great Cancelleria Palace, pilasters appear in the external composition, and all the details of doors and windows betray the results of classic study, as well as the refined taste of their designer.24 The beautiful courtyard of the Cancelleria combines the Florentine system of arches on columns with the Roman system of superposed arcades independent of the court wall. In 1506 Bramante began the rebuilding of St. Peter’s for Julius II. (see p. 294) and the construction of a new and imposing papal palace adjoining it on the Vatican hill. Of this colossal group of edifices, commonly known as the Vatican, he executed the greater Belvedere court (afterward divided in two by the Library and the Braccio Nuovo), the lesser octagonal court of the Belvedere, and the court of San Damaso, with its arcades afterward frescoed by Raphael and his school. Besides these, the cloister of S. M. della Pace, and many other works in and out of Rome, reveal the impress of Bramante’s genius, alike in their admirable plans and in the harmony and beauty of their details.

FLORENTINE PALACES. The P. Riccardi long remained the accepted type of palace in Florence. As we have seen, it was imitated in the Strozzi palace, as late as 1489, with 291 greater perfection of detail, but with no radical change of conception. In the P. Gondi, however, begun in the following year by Giuliano da San Gallo (1445–1516), a more pronounced classic spirit appears, especially in the court and the interior design. Early in the 16th century classic columns and pediments began to be used as decorations for doors and windows; the rustication was confined to basements and corner-quoins, and niches, loggias, and porches gave variety of light and shade to the façades (P. Bartolini, by Baccio d’Agnolo; P. Larderel, 1515, by Dosio; P. Guadagni, by Cronaca; P. Pandolfini, 1518, attributed to Raphael). In the P. Serristori, by Baccio d’Agnolo (1510), pilasters were applied to the composition of the façade, but this example was not often followed in Florence.

ROMAN PALACES. These followed a different type. They were usually of great size, and built around ample courts with arcades of classic model in two or three stories. The broad street façade in three stories with an attic or mezzanine was crowned with a rich cornice. The orders were sparingly used externally, and effect was sought principally in the careful proportioning of the stories, in the form and distribution of the square-headed and arched openings, and in the design of mouldings, string-courses, cornices, and other details. The piano nobile, or first story above the basement, was given up to suites of sumptuous reception-rooms and halls, with magnificent ceilings and frescoes by the great painters of the day, while antique statues and reliefs adorned the courts, vestibules, and niches of these princely dwellings. The Massimi palace, by Peruzzi, is an interesting example of this type. The Vatican, Cancelleria, and Giraud palaces have already been mentioned; other notable palaces are the Palma (1506) and Sacchetti (1540), by A. da San Gallo the Younger; the Farnesina, by Peruzzi, with celebrated fresco decorations designed by Raphael; 292 and the Lante (1520) and Altemps (1530), by Peruzzi. But the noblest creation of this period was the

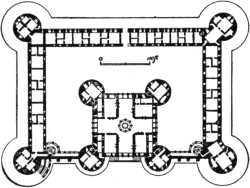

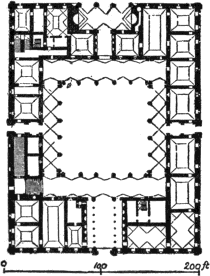

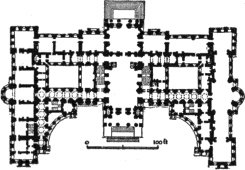

FIG. 167.—PLAN OF FARNESE PALACE.

Larger View

FARNESE PALACE, by many esteemed the finest in Italy. It was begun in 1530 for Alex. Farnese (Paul III.) by A. da San Gallo the Younger, with Vignola’s collaboration. The simple but admirable plan is shown in Fig. 167, and the courtyard, the most imposing in Italy, in Fig. 168. The exterior is monotonous, but the noble cornice by Michael Angelo measurably redeems this defect. The fine vaulted columnar entrance vestibule, the court and the salons, make up an ensemble worthy of the great architects who designed it. The loggia toward the river was added by G. della Porta in 1580.

VILLAS. The Italian villa of this pleasure-loving period afforded full scope for the most playful fancies of the architect, decorator, and landscape gardener. It comprised usually a dwelling, a casino or amusement-house, and many minor edifices, summer-houses, arcades, etc., disposed in extensive grounds laid out with terraces, cascades, and shaded alleys. The style was graceful, sometimes trivial, but almost always pleasing, making free use of stucco enrichments, both internally and externally, with abundance of gilding and frescoing. The Villa Madama (1516), by Raphael, with stucco-decorations by Giulio Romano, though incomplete and now dilapidated, is a noted example of the style. More complete, the Villa of Pope Julius, by Vignola (1550), belongs by its purity of style to this period; its façade well exemplifies the simplicity, 293 dignity, and fine proportions of this master’s work. In addition to these Roman villas may be mentioned the V. Medici (1540, by Annibale Lippi; now the French Academy of Rome); the Casino del Papa in the Vatican Gardens, by Pirro Ligorio (1560); the V. Lante, near Viterbo, and the V. d’Este, at Tivoli, as displaying among almost countless others the Italian skill in combining architecture and gardening.

FIG. 168.—ANGLE OF COURT OF FARNESE

PALACE, ROME.

CHURCHES AND CHAPELS. This period witnessed the building of a few churches of the first rank, but it was especially prolific in memorial, votive, and sepulchral chapels added to churches already existing, like the Chigi Chapel of S. M. del Popolo, by Raphael. The earlier churches of this period generally followed antecedent types, with the dome as the central feature dominating a cruciform plan, and simple, unostentatious and sometimes uninteresting exteriors. Among them may be mentioned: at Pistoia, S. M. del Letto and S. M. dell’ Umiltà, the latter a fine domical rotunda by Ventura Vitoni (1509), with an imposing vestibule; at Venice, S. Salvatore, by Tullio Lombardo (1530), an admirable edifice with alternating domical and barrel-vaulted bays; S. Georgio dei Grechi (1536), by Sansovino, and S. M. Formosa; at Todi, the Madonna della Consolazione (1510), by Cola da Caprarola, a charming design with a high dome and four apses; at Montefiascone, the Madonna delle Grazie, by Sammichele (1523), besides several churches at Bologna, Ferrara, Prato, Sienna, and Rome of almost or quite equal 294 interest. In these churches one may trace the development of the dome as an external feature, while in S. Biagio, at Montepulciano, the effort was made by Ant. da San Gallo the Elder to combine with it the contrasting lines of two campaniles, of which, however, but one was completed.

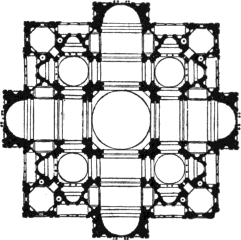

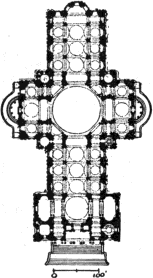

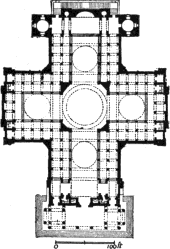

FIG. 169.—ORIGINAL PLAN OF ST. PETER’S, ROME.

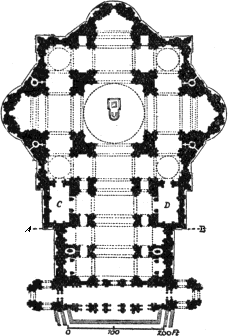

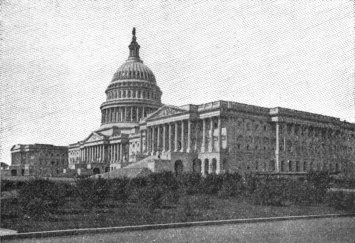

ST. PETER’S. The culmination of Renaissance church architecture was reached in St. Peter’s, at Rome. The original project of Nicholas V. having lapsed with his death, it was the intention of Julius II. to erect on the same site a stupendous mausoleum over the monument he had ordered of Michael Angelo. The design of Bramante, who began its erection in 1506, comprised a Greek cross with apsidal arms, the four angles occupied by domical chapels and loggias within a square outline (Fig. 169). The too hasty execution of this noble design led to the collapse of two of the arches under the dome, and to long delays after Bramante’s death in 1514. Raphael, Giuliano da San Gallo, Peruzzi, and A. da San Gallo the Younger successively supervised the works under the popes from Leo X. to Paul III., and devised a vast number of plans for its completion. Most of these involved fundamental alterations of the original scheme, and were motived by the abandonment of the proposed monument of Julius II.; a church, and not a mausoleum, being in consequence required. In 1546 Michael Angelo was assigned by Paul III. to the works, and gave final form to the general design in a simplified 295 version of Bramante’s plan with more massive supports, a square east front with a portico for the chief entrance, and the unrivalled Dome, which is its most striking feature. This dome, slightly altered and improved in curvature by della Porta after M. Angelo’s death in 1564, was completed by D. Fontana in 1604. It is the most majestic creation of the Renaissance, and one of the greatest architectural conceptions of all history. It measures 140 feet in internal diameter, and with its two shells rises from a lofty drum, buttressed by coupled Corinthian columns, to a height of 405 feet to the top of the lantern. The church, as left by Michael Angelo, was harmonious in its proportions, though the single order used internally and externally dwarfed by its colossal scale the vast dimensions of the edifice. Unfortunately in 1606 C. Maderna was employed by Paul V. to lengthen the nave by two bays, destroying the proportions of the whole, and hiding the dome from view on a near approach. The present tasteless façade was Maderna’s work. The splendid atrium or portico added (1629–67), by Bernini, as an approach, mitigates but does not cure the ugliness and pettiness of this front.

FIG. 170.—PLAN OF ST. PETER’S, ROME, AS NOW STANDING.

The portion below the line A, B, and the side chapels C, D, were added by Maderna. The remainder represents Michael Angelo’s plan.

St. Peter’s as thus completed (Fig. 170) is the largest 296 church in existence, and in many respects is architecturally worthy of its pre-eminence. The central aisle, nearly 600 feet long, with its stupendous panelled and gilded vault, 83 feet in span, the vast central area and the majestic dome, belong to a conception unsurpassed in majestic simplicity and effectiveness. The construction is almost excessively massive, but admirably disposed. On the other hand the nave is too long, and the details not only lack originality and interest, but are also too large and coarse in scale, dwarfing the whole edifice. The interior (Fig. 171) is wanting in the sobriety of color that befits so stately a design; it suggests rather a pagan temple than a Christian basilica. These faults reveal the decline of taste which had already set in before Michael Angelo took charge of the work, and which appears even in the works of that master.

THE PERIOD OF FORMAL CLASSICISM. With the middle of the 16th century the classic orders began to dominate all architectural design. While Vignola, who wrote a treatise upon the orders, employed them with unfailing refinement and judgment, his contemporaries showed less discernment and taste, making of them an end rather than a means. Too often mere classical correctness was substituted for the fundamental qualities of original invention ind intrinsic beauty of composition. The innovation of colossal orders extending through several stories, while it gave to exterior designs a certain grandeur of scale, tended to coarseness and even vulgarity of detail. Sculpture and ornament began to lose their refinement; and while street-architecture gained in monumental scale, and public squares received a more stately adornment than ever before, the street-façades individually were too often bare and uninteresting in their correct formality. In the interiors of churches and large halls there appears a struggle between a cold and dignified simplicity and a growing tendency toward pretentious sham. But these pernicious tendencies did 299 not fully mature till the latter part of the century, and the half-century after 1540 or 1550 was prolific of notable works in both ecclesiastical and secular architecture. The names of Michael Angelo and Vignola, whose careers began in the preceding period; of Palladio and della Porta (1541–1604) in Rome; of Sammichele and Sansovino in Verona and Venice, and of Galeazzo Alessi in Genoa, stand high in the ranks of architectural merit.

[297]

FIG. 171.—INTERIOR OF ST. PETER’S, ROME.

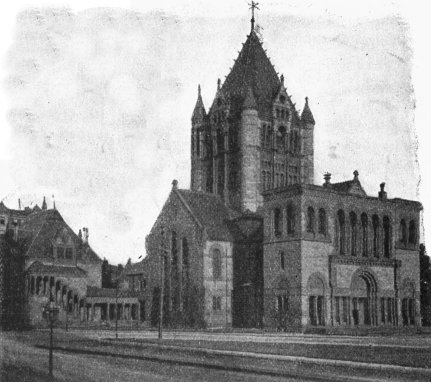

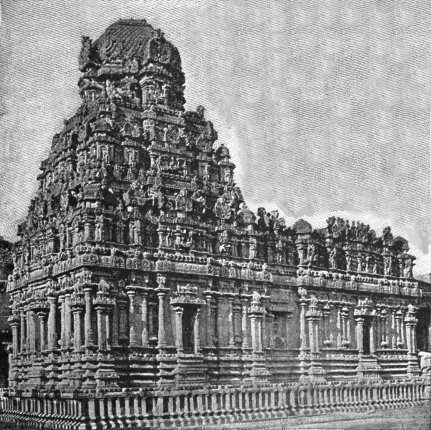

CHURCHES. The type established by St. Peter’s was widely imitated throughout Italy. The churches in which a Greek or Latin cross is dominated by a high dome rising from a drum and terminating in a lantern, and is treated both internally and externally with Roman Corinthian pilasters and arches, are almost numberless. Among the best churches of this type is the Gesù at Rome, by Vignola (1568), with a highly ornate interior of excellent proportions and a less interesting exterior, the façade adorned with two stories of orders and great flanking volutes over the sides (see p. 277). Two churches at Venice, by Palladio—S. Giorgio Maggiore (1560; façade by Scamozzi, 1575) and the Redentore—offer a strong contrast to the Gesù, in their cold and almost bare but pure and correct design. An imitation of Bramante’s plan for St. Peter’s appears in S. M. di Carignano, at Genoa, by Galeazzo Alessi (1500–72), begun 1552, a fine structure, though inferior in scale and detail to its original. Besides these and other important churches there were many large domical chapels of great splendor added to earlier churches; of these the Chapel of Sixtus V. in S. M. Maggiore, at Rome, by D. Fontana (1543–1607), is an excellent example.

PALACES: ROME. The palaces on the Capitoline Hill, built at different dates (1540–1644) from designs by Michael Angelo, illustrate the palace architecture of this period, and the imposing effect of a single colossal order running through two stories. This treatment, though well adapted 300 to produce monumental effects in large squares, was dangerous in its bareness and heaviness of scale, and was better suited for buildings of vast dimensions than for ordinary street-façades. In other Roman palaces of this time the traditions of the preceding period still prevailed, as in the Sapienza (University), by della Porta (1575), which has a dignified court and a façade of great refinement without columns or pilasters. The Papal palaces built by Domenico Fontana on the Lateran, Quirinal, and Vatican hills, between 1574 and 1590, externally copying the style of the Farnese, show a similar return to earlier models, but are less pure and refined in detail than the Sapienza. The great pentagonal Palace of Caprarola, near Rome, by Vignola, is perhaps the most successful and imposing production of the Roman classic school.

VERONA. Outside of Rome, palace-building took on various local and provincial phases of style, of which the most important were the closely related styles of Verona, Venice, and Vicenza. Michele Sammichele (1484–1549), who built in Verona the Bevilacqua, Canossa, Pompei, and Verzi palaces and the four chief city gates, and in Venice the P. Grimani, his masterpiece (1550), was a designer of great originality and power. He introduced into his military architecture, as in the gates of Verona, the use of rusticated orders, which he treated with skill and taste. The idea was copied by later architects and applied, with doubtful propriety, to palace-façades; though Ammanati’s garden-façade for the Pitti palace, in Florence (cir. 1560), is an impressive and successful design.

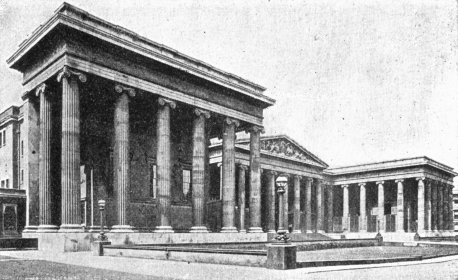

VENICE. Into the development of the maturing classic style Giacopo Tatti Sansovino (1477–1570) introduced in his Venetian buildings new elements of splendor. Coupled columns between arches themselves supported on columns, and a profusion of figure sculpture, gave to his palace-façades a hitherto unknown magnificence of effect, as 301 in the Library of St. Mark (now the Royal Palace, Fig. 172), and the Cornaro palace (P. Corner de Cà Grande), both dating from about 1530–40. So strongly did he impress upon Venice these ornate and sumptuous variations on classic themes, that later architects adhered, in a very debased period, to the main features and spirit of his work.

FIG. 172.—LIBRARY OF ST. MARK, VENICE.

VICENZA. Of Palladio’s churches in Venice we have already spoken; his palaces are mainly to be found in his native city, Vicenza. In these structures he displayed great fertility of invention and a profound familiarity with the classic orders, but the degenerate taste of the Baroque period already begins to show itself in his work. There is far less of architectural propriety and grace in these pretentious palaces, with their colossal orders and their affectation of grandeur, than in the designs of Vignola or Sammichele. Wood and plaster, used to mimic stone, indicate the approaching reign of sham in all design (P. Barbarano, 1570; Chieregati, 1560; Tiene, Valmarano, 1556; Villa Capra). His masterpiece is the two-storied arcade about the mediæval Basilica, in which the arches are supported on a minor order between engaged columns serving 302 as buttresses. This treatment has in consequence ever since been known as the Palladian Motive.

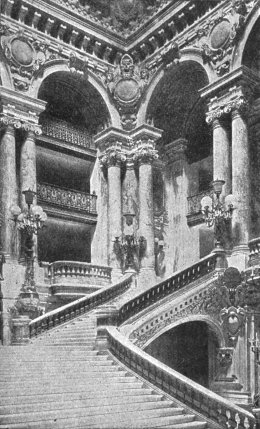

GENOA. During the second half of the sixteenth century a remarkable series of palaces was erected in Genoa, especially notable for their great courts and imposing staircases. These last were given unusual prominence owing to differences of level in the courts, arising from the slope of their sites on the hillside. Many of these palaces were by Galeazzo Alessi (1502–72); others by architects of lesser note; but nearly all characterized by their effective planning, fine stairs and loggias, and strong and dignified, if sometimes uninteresting, detail (P. Balbi, Brignole, Cambiasi, Doria-Tursi [or Municipio], Durazzo [or Reale], Pallavicini, and University).

FIG. 173.—INTERIOR OF SAN SEVERO, NAPLES.

THE BAROQUE STYLE. A reaction from the cold classicismo of the late sixteenth century showed itself in the following period, in the lawless and vulgar extravagances of the so-called Baroque style. The wealthy Jesuit order was a notorious contributor to the debasement of architectural taste. Most of the Jesuit churches and many others not belonging to the order, but following its pernicious example, are monuments of bad taste and pretentious sham. Broken 303 and contorted pediments, huge scrolls, heavy mouldings, ill-applied sculpture in exaggerated attitudes, and a general disregard for architectural propriety characterized this period, especially in its church architecture, to whose style the name Jesuit is often applied. Sham marble and heavy and excessive gilding were universal (Fig. 173). C. Maderna (1556–1629), Lorenzo Bernini (1589–1680), and F. Borromini (1599–1667) were the worst offenders of the period, though Bernini was an artist of undoubted ability, as proved by his colonnades or atrium in front of St. Peter’s. There were, however, architects of purer taste whose works even in that debased age were worthy of admiration.

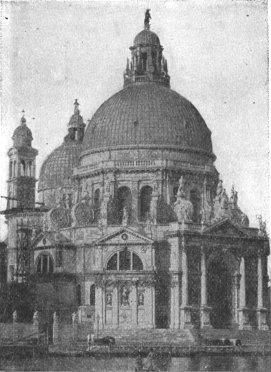

FIG. 174.—CHURCH OF S. M. DELLA SALUTE, VENICE.

BAROQUE CHURCHES. The Baroque style prevailed in church architecture for almost two centuries. The majority of the churches present varieties of the cruciform plan crowned by a high dome which is usually the best part of the design. Everywhere else the vices of the period appear in these churches, especially in their façades and internal decoration. S. M. della Vittoria, by Maderna, and Sta. Agnese, by Borromini, both at Rome, are examples of the 304 style. Naples is particularly full of Baroque churches (Fig. 173), a few of which, like the Gesù Nuovo (1584), are dignified and creditable designs. The domical church of S. M. della Salute, at Venice (1631), by Longhena, is also a majestic edifice in excellent style (Fig. 174), and here and there other churches offer exceptions to the prevalent baseness of architecture. Particularly objectionable was the wholesale disfigurement of existing monuments by ruthless remodelling, as in S. John Lateran, at Rome, the cathedrals of Ferrara and Ravenna, and many others.

PALACES. These were generally superior to the churches, and not infrequently impressive and dignified structures. The two best examples in Rome are the P. Borghese, by Martino Lunghi the Elder (1590), with a fine court arcade on coupled Doric and Ionic columns, and the P. Barberini, by Maderna and Borromini, with an elliptical staircase by Bernini, one of the few palaces in Italy with projecting lateral wings. In Venice, Longhena, in the Rezzonico and Pesaro palaces (1650–80), showed his freedom from the mannerisms of the age by reproducing successfully the ornate but dignified style of Sansovino (see p. 301). At Naples D. Fontana, whose works overlap the Baroque period, produced in the Royal Palace (1600) and the Royal Museum (1586–1615) designs of considerable dignity, in some respects superior to his papal residences in Rome. In suburban villas, like the Albani and Borghese villas near Rome, the ostentatious style of the Decline found free and congenial expression.

LATER MONUMENTS. In the few eighteenth-century buildings which are worthy of mention there is noticeable a reaction from the extravagances of the seventeenth century, shown in the dignified correctness of the exteriors and the somewhat frigid splendor of the interiors. The most notable work of this period is the Royal Palace at Caserta, by Van Vitelli (1752), an architect of considerable taste and inventiveness, considering his time. This great palace, 800 305 feet square, encloses four fine courts, and is especially remarkable for the simple if monotonous dignity of the well proportioned exterior and the effective planning of its three octagonal vestibules, its ornate chapel and noble staircase. Staircases, indeed, were among the most successful features of late Italian architecture, as in the Scala Regia of the Vatican, and in the Corsini, Braschi, and Barberini palaces at Rome, the Royal Palace at Naples, etc.

In church architecture the east front of S. John Lateran in Rome, by Galilei (1734), and the whole exterior of S. M. Maggiore, by Ferd. Fuga (1743), are noteworthy designs: the former an especially powerful conception, combining a colossal order with two smaller orders in superposed loggie, but marred by the excessive scale of the statues which crown it. The Fountain of Trevi, conceived in much the same spirit (1735, by Niccola Salvi), is a striking piece of decorative architecture. The Sacristy of St. Peter’s, by Marchionne (1775), also deserves mention as a monumental and not uninteresting work. In the early years of the present century the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican, by Stern, the imposing church of S. Francesco di Paola at Naples, by Bianchi, designed in partial imitation of the Pantheon, and the great S. Carlo Theatre at Naples, show the same coldly classical spirit, not wholly without merit, but lacking in true originality and freedom of conception.

CAMPANILES. The campaniles of the Renaissance and Decline deserve at least passing reference, though they are neither numerous nor often of conspicuous interest. That of the Campidoglio (Capitol) at Rome, by Martino Lunghi, is a good example of the classical type. Venetia possesses a number of graceful and lofty bell-towers, generally of brick with marble bell-stages, of which the upper part of the Campanile of St. Mark and the tower of S. Giorgio Maggiore are the finest examples.

The Decline attained what the early Renaissance aimed 306 at—the revival of Roman forms. But it was no longer a Renaissance; it was a decrepit and unimaginative art, held in the fetters of a servile imitation, copying the letter rather than the spirit of antique design. It was the mistaken and abject worship of precedent which started architecture upon its downward path and led to the atrocious products of the seventeenth century.

MONUMENTS (mainly in addition to those mentioned in the text). 15th Century—Florence: Foundling Hospital (Innocenti), 1421; Old Sacristy and Cloister S. Lorenzo; P. Quaratesi, 1440; cloisters at Sta. Croce and Certosa, all by Brunelleschi; façade S. M. Novella, by Alberti, 1456; Badia at Fiesole, from designs of Brunelleschi, 1462; Court of P. Vecchio, by Michelozzi, 1464 (altered and enriched, 1565); P. Guadagni, by Cronaca, 1490; Hall of 500 in P. Vecchio, by same, 1495.—Venice: S. Zaccaria, by Martino Lombardo, 1457–1515; S. Michele, by Moro Lombardo, 1466; S. M. del Orto, 1473; S. Giovanni Crisostomo, by Moro Lombardo, atrium of S. Giovanni Evangelista, Procurazie Vecchie, all 1481; Scuola di S. Marco, by Martino Lombardo, 1490; P. Dario; P. Corner-Spinelli.—Ferrara: P. Schifanoja, 1469; P. Scrofa or Costabili, 1485; S. M. in Vado, P. dei Diamanti, P. Bevilacqua, S. Francesco, S. Benedetto, S. Cristoforo, all 1490–1500.—Milan: Ospedale Grande (or Maggiore), begun 1457 by Filarete, extended by Bramante, cir. 1480–90 (great court by Richini, 17th century); S. M. delle Grazie, E. end, Sacristy of S. Satiro, S. M. presso S. Celso, all by Bramante, 1477–1499.—Rome: S. Pietro in Montorio, 1472; S. M. del Popolo, 1475?; Sistine Chapel of Vatican, 1475; S. Agostino, 1483.—Sienna: Loggia del Papa and P. Nerucci, 1460; P. del Governo, 1469–1500; P. Spannocchi, 1470; Sta. Catarina, 1490, by di Bastiano and Federighi, church later by Peruzzi; Library in cathedral by L. Marina, 1497; Oratory of S. Bernardino, by Turrapili, 1496.—Pienza: Cathedral, Bishop’s Palace (Vescovado), P. Pubblico, all cir. 1460, by B. di Lorenzo (or Rosselini?). Elsewhere (in chronological order): Arch of Alphonso, Naples, 1443, by P. di Martino; Oratory S. Bernardino, Perugia, by di Duccio, 1461; Church over Casa-Santa, Loreto, 1465–1526; P. del Consiglio at Verona, by Fra Giocondo, 1476; Capella Colleoni, Bergamo, 1476; S. M. in Organo, Verona, 1481; Porta Capuana, Naples, by Giul. da Majano, 1484; Madonna della Croce, Crema, by B. Battagli, 1490–1556; Madonna di Campagna and S. Sisto, Piacenza, both 1492–1511; P. Bevilacqua, Bologna, by Nardi, 1492 (?); P. Gravina, Naples; P. Fava, Bologna; P. Pretorio, Lucca; S. M. dei Miracoli Brescia; all at close of 15th century.

30716th Century—Rome: P. Sora, 1501; S. M. della Pace and cloister, 1504, both by Bramante (façade of church by P. da Cortona, 17th century); S. M. di Loreto, 1507, by A. da San Gallo the Elder; P. Vidoni, by Raphael; P. Lante, 1520; Vigna Papa Giulio, 1534, by Peruzzi; P. dei Conservatori, 1540, and P. del Senatore, 1563 (both on Capitol), by M. Angelo, Vignola, and della Porta; Sistine Chapel in S. M. Maggiore, 1590; S. Andrea della Valle, 1591, by Olivieri (façade, 1670, by Rainaldi).—Florence: Medici Chapel of S. Lorenzo, new sacristy of same, and Laurentian Library, all by M. Angelo, 1529–40; Mercato Nuovo, 1547, by B. Tasso; P. degli Uffizi, 1560–70, by Vasari; P. Giugni, 1560–8.—Venice: P. Camerlinghi, 1525, by Bergamasco; S. Francesco della Vigna, by Sansovino, 1539, façade by Palladio, 1568; Zecca or Mint, 1536, and Loggetta of Campanile, 1540, by Sansovino25, Procurazie Nuove, 1584, by Scamozzi.—Verona: Capella Pellegrini in S. Bernardino, 1514; City Gates, by Sammichele, 1530–40 (Porte Nuova, Stuppa, S. Zeno, S. Giorgio).—Vicenza: P. Porto, 1552; Teatro Olimpico, 1580; both by Palladio.—Genoa: P. Andrea Doria, by Montorsoli, 1529; P. Ducale, by Pennone, 1550; P. Lercari, P. Spinola, P. Sauli, P. Marcello Durazzo, all by Gal. Alessi, cir. 1550; Sta. Annunziata, 1587, by della Porta; Loggia dei Banchi, end of 16th century.—Elsewhere (in chronological order). P. Roverella, Ferrara, 1508; P. del Magnifico, Sienna, 1508, by Cozzarelli; P. Communale, Brescia, 1508, by Formentone; P. Albergati, Bologna, 1510; P. Ducale, Mantua, 1520–40; P. Giustiniani, Padua, by Falconetto, 1524; Ospedale del Ceppo, Pistoia, 1525; Madonna delle Grazie, Pistoia, by Vitoni, 1535; P. Buoncampagni-Ludovisi, Bologna, 1545; Cathedral, Padua, 1550, by Righetti and della Valle, after M. Angelo; P. Bernardini, 1560, and P. Ducale, 1578, at Lucca, both by Ammanati.

17th Century: Chapel of the Princes in S. Lorenzo, Florence, 1604, by Nigetti; S. Pietro, Bologna, 1605; S. Andrea delle Fratte, Rome, 1612; Villa Borghese, Rome, 1616, by Vasanzio; P. Contarini delle Scrigni, Venice, by Scamozzi; Badia at Florence, rebuilt 1625 by Segaloni; S. Ignazio, Rome, 1626–85; Museum of the Capitol, Rome, 1644–50; Church of Gli Scalzi, Venice, 1649; P. Pesaro, Venice, by Longhena, 1650; S. Moisé, Venice, 1668; Brera Palace, Milan; S. M. Zobenigo, Venice, 1680; Dogana di Mare, Venice, 1686, by Benone; Santi Apostoli, Rome.

18th and early 19th Century: Gesuati, at Venice, 1715–30; S. Geremia, Venice, 1753, by Corbellini; P. Braschi, Rome, by Morelli, 1790; Nuova Fabbrica, Venice, 1810.

24. See Appendix C.

25. See Appendix B.

CHAPTER XXII.

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE.

Books Recommended: As before, Fergusson, Müntz, Palustre. Also Berty, La Renaissance monumentale en France. Château, Histoire et caractères de l’architecture en France. Daly, Motifs historiques d’architecture et de sculpture. De Laborde, La Renaissance des arts à la cour de France. Du Cerceau, Les plus excellents bastiments de France. Lübke, Geschichte der Renaissance in Frankreich. Mathews, The Renaissance under the Valois Kings. Palustre, La Renaissance en France. Pattison, The Renaissance of the Fine Arts in France. Rouyer et Darcel, L’Art architectural en France. Sauvageot, Choix de palais, châteaux, hôtels, et maisons de France.

ORIGIN AND CHARACTER. The vitality and richness of the Gothic style in France, even in its decline in the fifteenth century, long stood in the way of any general introduction of classic forms. When the Renaissance appeared, it came as a foreign importation, introduced from Italy by the king and the nobility. It underwent a protracted transitional phase, during which the national Gothic forms and traditions were picturesquely mingled with those of the Renaissance. The campaigns of Charles VIII. (1489), Louis XII. (1499), and Francis I. (1515), in vindication of their claims to the thrones of Naples and Milan, brought these monarchs and their nobles into contact with the splendid material and artistic civilization of Italy, then in the full tide of the maturing Renaissance. They returned to France, filled with the ambition to rival the splendid palaces and gardens of Italy, taking with them Italian artists to teach their arts to the French. But while these Italians successfully 309 introduced many classic elements and details into French architecture, they wholly failed to dominate the French master-masons and tailleurs de pierre in matters of planning and general composition. The early Renaissance architecture of France is consequently wholly unlike the Italian, from which it derived only minor details and a certain largeness and breadth of spirit.

PERIODS. The French Renaissance and its sequent developments may be broadly divided into three periods, with subdivisions coinciding more or less closely with various reigns, as follows:

I. The Valois Period, or Renaissance proper, 1483–1589, subdivided into:

a. The Transition, comprising the reigns of Charles VIII. and Louis XII. (1483–1515), and the early years of that of Francis I.; characterized by a picturesque mixture of classic details with Gothic conceptions.

b. The Style of Francis I., or Early Renaissance, from about 1520 to that king’s death in 1547; distinguished by a remarkable variety and grace of composition and beauty of detail.

c. The Advanced Renaissance, comprising the reigns of Henry II. (1547), Francis II. (1559), Charles IX. (1560), and Henry III. (1574–89); marked by the gradual adoption of the classic orders and a decline in the delicacy and richness of the ornament.

II. The Bourbon or Classic Period (1589–1715):

a. Style of Henry IV., covering his reign and partly that of Louis XIII. (1610–45), employing the orders and other classic forms with a somewhat heavy, florid style of ornament.

b. Style of Louis XIV., beginning in the preceding reign and extending through that of Louis XIV. (1645–1715); the great age of classic architecture in France, corresponding to the Palladian in Italy.

310III. The Decline or Rococo Period, corresponding with the reign of Louis XV. (1715–74); marked by pompous extravagance and capriciousness.

During this period a reaction set in toward a severer classicism, leading to the styles of Louis XVI. and of the Empire, to be treated of in a later chapter.

THE TRANSITION. As early as 1475 the new style made its appearance in altars, tombs, and rood-screens wrought by French carvers with the collaboration of Italian artificers. The tomb erected by Charles of Anjou to his father in Le Mans cathedral (1475, by Francesco Laurana), the chapel of St. Lazare in the cathedral of Marseilles (1483), and the tomb of the children of Charles VIII. in Tours cathedral (1506), by Michel Columbe, the greatest artist of his time in France, are examples. The schools of Rouen and Tours were especially prominent in works of this kind, marked by exuberant fancy and great delicacy of execution. In church architecture Gothic traditions were long dominant, in spite of the great numbers of Italian prelates in France. It was in châteaux, palaces, and dwellings that the new style achieved its most notable triumphs.

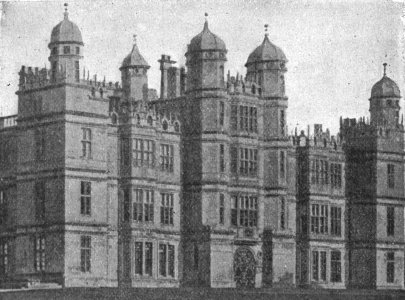

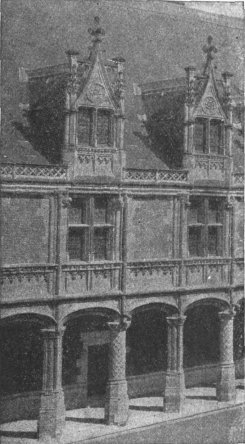

EARLY CHÂTEAUX. The castle of Charles VIII., at Amboise on the Loire, shows little trace of Italian influence. It was under Louis XII. that the transformation of French architecture really began. The Château de Gaillon (of which unfortunately only fragments remain in the École des Beaux-Arts at Paris), built for the Cardinal George of Amboise, between 1497 and 1509, by Pierre Fain, was the masterwork of the Rouen school. It presented a curious mixture of styles, with its irregular plan, its moat, drawbridge, and round corner-towers, its high roofs, turrets, and dormers, which gave it, in spite of many Renaissance details, a mediæval picturesqueness. The Château de Blois (the east and south wings of the present group), begun for Louis XII. about 1500, was the first of a remarkable series 311 of royal palaces which are the glory of French architecture. It shows the new influences in its horizontal lines and flat, unbroken façades of brick and stone, rather than in its architectural details (Fig. 175). The Ducal Palace at Nancy and the Hôtel de Ville at Orléans, by Viart, show a similar commingling of the classic and mediæval styles.

FIG. 175.—BLOIS, COURT FAÇADE OF WING OF

LOUIS XII.

STYLE OF FRANCIS I. Early in the reign of this monarch, and partly under the lead of Italian artists, like il Rosso, Serlio, and Primaticcio, classic elements began to dominate the general composition and Gothic details rapidly disappeared. A simple and effective system of exterior design was adopted in the castles and palaces of this period. Finely moulded belt-courses at the sills and heads of the windows marked the different stories, and were crossed by a system of almost equally important vertical lines, formed by superposed pilasters flanking the windows continuously from basement to roof. The façade was crowned by a slight cornice and open balustrade, above which rose a steep and lofty roof, diversified by elaborate dormer windows which were 312 adorned with gables and pinnacles (Fig. 178). Slender pilasters, treated like long panels ornamented with arabesques of great beauty, or with a species of baluster shaft like a candelabrum, were preferred to columns, and were provided with graceful capitals of the Corinthianesque type. The mouldings were minute and richly carved; pediments were replaced by steep gables, and mullioned windows with stone crossbars were used in preference to the simpler Italian openings. In the earlier monuments Gothic details were still used occasionally; and round corner-towers, high dormers, and numerous turrets and pinnacles appear even in the châteaux of later date.

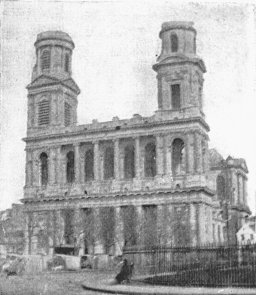

CHURCHES. Ecclesiastical architecture received but scant attention under Francis I., and, so far as it was practised, still clung tenaciously to Gothic principles. Among the few important churches of this period may be mentioned St. Etienne du Mont, at Paris (1517–38), in which classic and Gothic features appear in nearly equal proportions; the east end of St. Pierre, at Caen, with rich external carving; and the great parish church of St. Eustache, at Paris (1532, by Lemercier), in which the plan and construction are purely Gothic, while the details throughout belong to the new style, though with little appreciation of the spirit and proportions of classic art. New façades were also built for a number of already existing churches, among which St. Michel, at Dijon, is conspicuous, with its vast portal arch and imposing towers. The Gothic towers of Tours cathedral were completed with Renaissance lanterns or belfries, the northern in 1507, the southern in 1547.

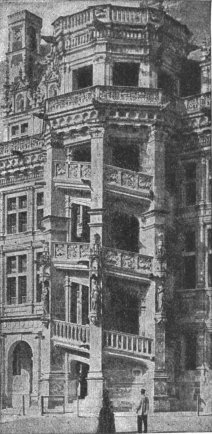

FIG. 176.—STAIRCASE TOWER, BLOIS.

PALACES. To the palace at Blois begun by his predecessor, Francis I. added a northern and a western wing, completing the court. The north wing is one of the masterpieces of the style, presenting toward the court a simple and effective composition, with a rich but slightly projecting cornice and a high roof with elaborate dormers. This 313 façade is divided into two unequal sections by the open Staircase Tower (Fig. 176), a chef-d’œuvre in boldness of construction as well as in delicacy and richness of carving. The outer façade of this wing is a less ornate but more vigorous design, crowned by a continuous open loggia under the roof. More extensive than Blois was Fontainebleau, the favorite residence of the king and of many of his successors. Following in parts the irregular plan of the convent it replaced, its other portions were more symmetrically disposed, while the whole was treated externally in a somewhat severe, semi-classic style, singularly lacking in ornament. Internally, however, this palace, begun in 1528 by Gilles Le Breton, was at that time the most splendid in France, the gallery of Francis I. being especially noted. The Château of St. Germain, near Paris (1539, by Pierre Chambiges), is of a very different character. Built largely of brick, with flat balustraded roof and deep buttresses carrying three ranges of arches, it is neither Gothic nor classic, neither fortress nor palace in aspect, but a wholly unique conception.

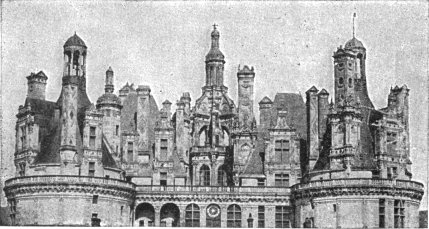

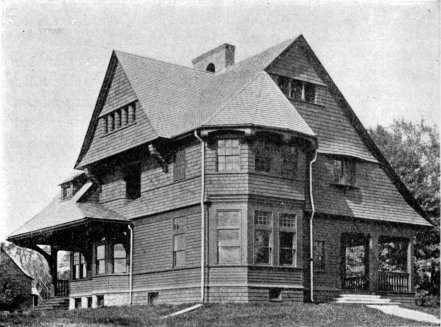

The rural châteaux and hunting-lodges erected by Francis I. display the greatest diversity of plan and treatment, 314 attesting the inventiveness of the French genius, expressing itself in a new-found language, whose formal canons it disdained. Chief among them is the Château of Chambord (Figs. 177, 178)—“a Fata Morgana in the midst of a wild, woody thicket,” to use Lübke’s language. This extraordinary edifice, resembling in plan a feudal castle with curtain-walls, bastions, moat, and donjon, is in its architectural treatment a palace with arcades, open-stair towers, a noble double spiral staircase terminating in a graceful lantern, and a roof of the most bewildering complexity of towers, chimneys, and dormers (1526, by Pierre le Nepveu). The hunting-lodges of La Muette and Chalvau, and the so-called Château de Madrid—all three demolished during or since the Revolution—deserve mention, especially 315 the last. This consisted of two rectangular pavilions, connected by a lofty banquet-hall, and adorned externally with arcades in Florentine style, and with medallions and reliefs of della Robbia ware (1527, by Gadyer).

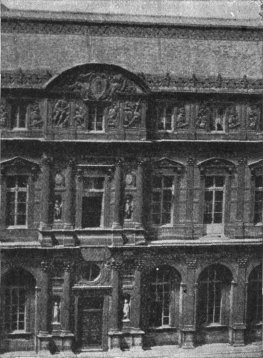

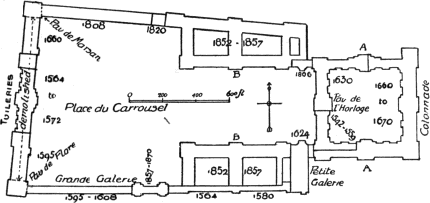

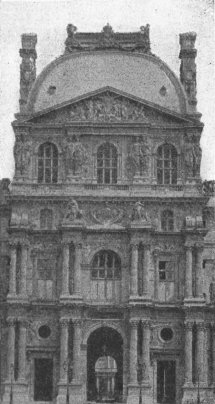

THE LOUVRE. By far the most important of all the architectural enterprises of this reign, in ultimate results, if not in original extent, was the beginning of a new palace to replace the old Gothic fortified palace of the Louvre. To this task Pierre Lescot was summoned in 1542, and the work of erection actually begun in 1546. The new palace, in a sumptuous and remarkably dignified classic style, was to have covered precisely the area of the demolished fortress. Only the southwest half, comprising two sides of the court, was, however, undertaken at the outset (Fig. 179). It remained for later monarchs to amplify the original scheme, and ultimately to complete, late in the present century, the most extensive and beautiful of all the royal residences of Europe. (See Figs. 181, 208, 209.)

FIG. 179.—DETAIL OF COURT OF LOUVRE, PARIS.

Want of space forbids more than a passing reference to the rural castles of the nobility, rivalling those of the king. Among them Bury, La Rochefoucauld, Bournazel, and 316 especially Azay-le-Rideau (1520) and Chenonceaux (1515–23), may be mentioned, all displaying that love of rural pleasure, that hatred of the city and its confinement, which so distinguish the French from the Italian Renaissance.

OTHER BUILDINGS. The Hôtel-de-Ville (town hall), of Paris, begun during this reign, from plans by Domenico di Cortona (?), and completed under Henry IV., was the most important edifice of a class which in later periods numbered many interesting structures. The town hall of Beaugency (1527) is one of the best of minor public buildings in France, and in its elegant treatment of a simple two-storied façade may be classed with the Maison François I., at Paris. This stood formerly at Moret, whence it was transported to Paris and re-erected about 1830 in somewhat modified form. The large city houses of this period are legion; we can mention only the Hôtel Carnavalet at Paris; the Hôtel Bourgtheroude at Rouen; the Hôtel d’Écoville at Caen; the archbishop’s palace at Sens, and a number of houses in Orléans. The Tomb of Louis XII., at St. Denis, deserves especial mention for its fine proportions and beautiful arabesques.

THE ADVANCED RENAISSANCE. By the middle of the sixteenth century the new style had lost much of its earlier charm. The orders, used with increasing frequency, were more and more conformed to antique precedents. Façades were flatter and simpler, cornices more pronounced, arches more Roman in treatment, and a heavier style of carving took the place of the delicate arabesques of the preceding age. The reigns of Henry II. (1547–59) and Charles IX. (1560–74) were especially distinguished by the labors of three celebrated architects: Pierre Lescot (1515–78), who continued the work on the southwest angle of the Louvre; Jean Bullant (1515–78), to whom are due the right wing of Ecouen and the porch of colossal Corinthian columns in the left wing of the same, built under Francis I.; and, finally, Philibert de l’Orme (1515–70). Jean Goujon (1510–72) also 317 executed during this period most of the remarkable architectural sculptures which have made his name one of the most illustrious in the annals of French art. Chief among the works of de l’Orme was the palace of the Tuileries, built under Charles IX. for Cathérine de Médicis, not far from the Louvre, with which it was ultimately connected by a long gallery. Of the vast plan conceived for this palace, and comprising a succession of courts and wings, only a part of one side was erected (1564–72). This consisted of a domical pavilion, flanked by low wings only a story and a half high, to which were added two stories under Henry IV., to the great advantage of the design. Another masterpiece was the Château d’Anet, built in 1552 by Henry II. for Diane de Poitiers, of which, unfortunately, only fragments survive. This beautiful edifice, while retaining the semi-military moat and bastions of feudal tradition, was planned with classic symmetry, adorned with superposed orders, court arcades, and rectangular corner-pavilions, and provided with a domical cruciform chapel, the earliest of its class in France. All the details were unusually pure and correct, with just enough of freedom and variety to lend a charm wanting in later works of the period. To the reign of Henry II. belong also the châteaux of Ancy-le-Franc, Verneuil, Chantilly (the “petit château,” by Bullant), the banquet-hall over the bridge at Chenonceaux (1556), several notable residences at Toulouse, and the tomb of Francis I. at St. Denis. The châteaux of Pailly and Sully, distinguished by the sobriety and monumental quality of their composition, in which the orders are important elements, belong to the reign of Charles IX., together with the Tuileries, already mentioned.

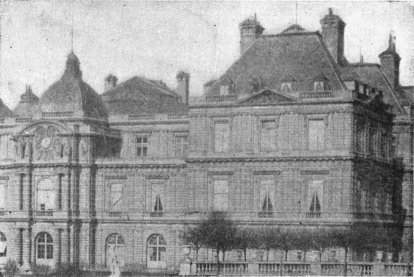

FIG. 180.—THE LUXEMBURG, PARIS.

THE CLASSIC PERIOD: HENRY IV. Under this energetic but capricious monarch (1589–1610) and his Florentine queen, Marie de Médicis, architecture entered upon a new period of activity and a new stage of development. Without the 318 charm of the early Renaissance or the stateliness of the age of Louis XIV., it has a touch of the Baroque, attributable partly to the influence of Marie de Médicis and her Italian prelates, and partly to the Italian training of many of the French architects. The great work of this period was the extension of the Tuileries by J. B. du Cerceau, and the completion, by Métézeau and others, of the long gallery next the Seine, begun under Henry II., with the view of connecting the Tuileries with the Louvre. In this part of the work colossal orders were used with indifferent effect. Next in importance was the addition to Fontainebleau of a great court to the eastward, whose relatively quiet and dignified style offers less contrast than one might expect to the other wings and courts dating from Francis I. More successful architecturally than either of the above was the Luxemburg palace, built for the queen by Salomon De Brosse, in 1616 (Fig. 180). Its plan presents the favorite French arrangement of a main building separated from the street 319 by a garden or court, the latter surrounded on three sides by low wings containing the dependencies. Externally, rusticated orders recall the garden front of the Pitti at Florence; but the scale is smaller, and the projecting pavilions and high roofs give it a grace and picturesqueness wanting in the Florentine model. The Place Royale, at Paris, and the château of Beaumesnil, illustrate a type of brick-and-stone architecture much in vogue at this time, stone quoins decorating the windows and corners, and the orders being generally omitted.

Under Louis XIII. the Tuileries were extended northward and the Louvre as built by Lescot was doubled in size by the architect Lemercier, the Pavillon de l’Horloge being added to form the centre of the enlarged court façade.

CHURCHES. To this reign belong also the most important churches of the period. The church of St. Paul-St. Louis, at Paris (1627, by Derrand), displays the worst faults of the time, in the overloaded and meaningless decoration of its uninteresting front. Its internal dome is the earliest in Paris. Far superior was the chapel of the Sorbonne, a well-designed domical church by Lemercier, with a sober and appropriate exterior treated with superposed orders.