This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Raftmates

A Story of the Great River

Author: Kirk Munroe

Release Date: September 16, 2006 [eBook #19303]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAFTMATES***

Although the Venture was by no means so large a raft as many that Winn Caspar had watched glide down the Mississippi, he considered it about the finest craft of that description ever put together. He was also a little more proud of it than of anything else in the whole world. Of course he excepted his brave soldier father, who had gone to the war as a private, to come home when it was all over wearing a major's uniform; and his dear mother, who for four weary years had been both father and mother to him, and his sister Elta, who was not only the prettiest girl in the county, but, to Winn's mind, the cleverest. But outside of his immediate family, the raft, the Venture, as his father had named it, was the object of the boy's most sincere admiration and pride. Had he not helped build it? Did he not know every timber and plank and board in it? Had he not assisted in loading it with enough bushels of wheat to feed an army? Was he not about to leave home for the first time in his life, to float away down the great river and out into the wide world on it? Certainly he had, and did, and was. So no wonder he was proud of the raft, and impatient for the waters of the little river, on a bank of which the Caspar's lived, to be high enough to float it, that they might make a start.

Winn had never known any home but this one near the edge of the vast pine forests of Wisconsin. Here Major Caspar had brought his New England bride many years before. Here he had built up a mill business that was promising him a fortune in a few years more at the time when the war called him. When peace was declared, this business was wellnigh ruined, and the soldier must begin life again as a poor man. For many months he struggled, but made little head-way against adverse fortune. The mill turned out lumber fast enough, but there was no demand for it, or those who wanted it were too poor to pay its price. At length the Major decided upon a bold venture. The Caspar mill was but a short distance from the Mississippi. Far away down the great river were cities where money was plenty, and where lumber and farm products were in demand. There were not half enough steamboats on the river, and freights were high; but the vast waterway with its ceaseless current was free to all. Why should not he do as others had done and were constantly doing—raft his goods to a market? It would take time, of course; but a few months of the autumn and winter could be spared as well as not, and so it was finally decided that the venture should be undertaken.

It was not to be a timber raft only. Major Caspar did not care to attempt the navigating of a huge affair, such as his entire stock of sawed material would have made, nor could he afford the expense of a large crew. Then, too, while ready money was scarce in his neighborhood, the prairie wheat crop of that season was unusually good. So he exchanged half his lumber for wheat, and devoted his leisure during the summer to the construction of a raft with the remainder.

This raft contained the very choice of the mill's output for that season—squared timbers, planks, and boards enough to load a ship. It was provided with two long sweeps, or steering oars, at each end, with a roomy shanty for the accommodation of the crew, and with two other buildings for the stowing of cargo. The floors of these structures were raised a foot above the deck of the raft, and were made water-tight, so that when waves or swells from passing steamboats broke over the raft, their contents would not be injured. In front of the central building, or "shanty," was a bed of sand six feet square, enclosed by wooden sides, on which the camp-fires were to be built. Much of the cooking would also be done here. Besides this there was a small stove in the "shanty" for use during cold or wet weather.

The "shanty" had a door and three windows, and was in other ways made unusually comfortable. The Major said that after four years of roughing it, he now meant to take his comfort wherever he could find it, even though it was only on a raft. So the Venture's "shanty" was very different from the rude lean-to or shelter of rough boards, such as was to be seen on most of the timber rafts of the great river. Its interior was divided into two rooms, the after one of which was a tiny affair only six by ten feet. It was furnished with two bunks, one above the other, a table, two camp-chairs, and several shelves, on one of which were a dozen books of travel and history. This was the sleeping-room that Winn was to share with his father.

A door from this opened into the main living-room of the "shanty." Here were bunks for six men, a dining-table, several benches, barrels, and boxes of provisions, and the galley, with its stove and ample supply of pots, pans, and dishes. The bunks were filled with fresh, sweet-smelling wheat straw, covered with heavy army blankets, and the whole affair was about the most comfortable "shanty" ever set up on a Mississippi timber raft. To Winn it seemed as though nothing could be more perfect or inviting, and he longed for the time when it should be his temporary home.

For a whole month after the raft was finished, loaded, and ready to set forth on its uncertain voyage, it remained hard and fast aground where it was built. To Winn's impatience it seemed as though high-water never would come.

"I don't believe this old raft is ever going to float any more than the mill itself," he remarked pettishly to his sister Elta one day in October, as they sat together on the Venture and watched the sluggish current of the little river.

"Father thinks it will," answered Elta, quietly.

"Oh yes. Of course father thinks so; but he may be mistaken as well as other folks. Now if I'd had the building of this craft, I would have floated all the material down to the mouth of the creek. Then everything would have been ready for a start as soon as she was finished."

"How would you have loaded the wheat?" demanded Elta.

"Why, boated it down, of course."

"And so added largely to its cost," answered the practical girl. "You know, Winn, that it was ever so much cheaper to build the raft here than it would have been 'way down there, and, besides, father wasn't ready to start when it was finished. I heard him tell mother that he didn't care to get away before the 1st of November. Anyhow, father must understand his own business better than a sixteen-year-old boy, even if that boy's name is Winn Caspar."

"Oh, I never saw such a girl as you are!" exclaimed Winn, impatiently. "You are always making objections to my plans, and telling me that I'm only a boy. You'd rather any time travel in a rut that some one else had made than mark out a track for yourself. For my part, I'd much rather think out my own plans and try new ways."

"So do I, Winnie; but—"

"Oh, don't call me 'Winnie,' whatever you do! I'm as tired of pet names and baby talk as I am of waiting here for high-water that won't ever come."

With this the petulant lad rose to his feet, and leaping ashore, disappeared among the trees of the river-bank, leaving Elta to gaze after him with a grieved expression, and a suspicion of tears in her brown eyes.

In spite of this little scene, Winn Caspar was not an ill-tempered boy. He had not learned the beauty of self-control, and thus often spoke hastily, and without considering the feelings of others. He was also apt to think that if things were left to his management, he could improve upon almost any plan proposed or carried out by some one else. He had mingled but little with other boys, and as "man of the family" during his father's four years of absence in the army, had conceived a false estimate of his own importance and ability.

Absorbed by pressing business cares after resuming the pursuits of a peaceful life, Major Caspar had been slow to note the imperfections in his boy's character. He was deeply grieved when his eyes were finally opened to them, and held many an earnest consultation with his wife concerning the son, who was at once the source of their greatest anxiety and the object of their fondest hopes.

It was during one of these conversations with the boy's mother that Major Caspar decided to take Winn with him on his raft voyage down the Mississippi.

"If I find a good chance to place the boy in a first-class school in one of the large cities after the voyage is ended I shall do so," said the Major. "It is only fair, though, that he should have a chance to see and learn something of the world first. After all, there is nothing equal to travel as an educator. I honestly believe that the war did more in four years towards educating this nation by stirring its people up and moving large bodies of them to sections remote from their homes than all our colleges have in fifty."

"But you mean that Winn shall go to college, of course?" said Mrs. Caspar, a little anxiously.

"If he wants to, and shows a real liking for study," was the reply; "but not unless he does. College is by no means the only place where a boy can receive a liberal education. He may acquire just as good a one in practical life if he is thoroughly interested in what he is doing and has an ambition to excel. I believe Winn to be both ambitious and persevering; but he is impulsive, easily influenced, and impatient of control. He has no idea of that implicit obedience to orders that is at the foundation of success in civil life as well as in the army; and, above all, he is possessed of such an inordinate self-conceit that if it is not speedily curbed by one or more severe lessons, it may lead him into serious trouble."

"Oh, John!" expostulated the mother. "Do you realize that you are saying these horrid things about our own boy—our Winn?"

"Indeed I do, dear," answered the Major, smiling; "and it is because he is our boy, whom I love better than myself, that I am analyzing his character so carefully. He has the making of a splendid fellow in him, together with certain traits that might easily prove his ruin."

"Well," replied Mrs. Caspar, in a resigned tone, "perhaps it will do him good to go away and be alone with you for a while. It is very hard to realize, though, that my little Winn is sixteen years old and almost a man. But, John, you won't let him run any risks, or get into any danger, will you?"

"Not knowingly, my dear, you may rest assured," answered the Major. But he smiled as he thought how impossible it was to keep boys from running risks and getting into all sorts of dangerous positions.

So it was decided that Winn should form one of the crew of the Venture whenever the raft should be ready to start on its long voyage; and ever since learning tins decision the boy had been in a fever of impatience to be off. So full was he of anticipations concerning the proposed journey that he could talk and think of nothing else. Thus, after a month of tiresome delay, he was in such an uncomfortable frame of mind that it was a positive trial to have him about the house. For this reason he was encouraged to spend much of his time aboard the raft, and was even allowed to eat and sleep there whenever he chose. At length he reached the point of almost quarrelling with his sister, whom he loved so dearly; but he had hardly plunged into the woods, after leaving her on the raft, before he regretted his unkind words and heartily wished them unsaid. He hesitated and half turned back, but his "pride," as he would have called it, though it was really nothing but cowardice, was too strong to permit him to humble himself just yet. So, feeling very unhappy, he tramped moodily on through the woods, full of bitter thoughts, angry with himself and all the world. Yet if any one had asked him what it was all about, he could not have told.

Winn took a long circuit through the silent forest, and by the time he again reached the river-bank, coming out just above the mill, he had walked himself tired, but into quite a cheerful frame of mind. The mill was shut down for the night, its workers had gone home, and not a sound broke the evening stillness. The boy sat on a pile of slabs for a few minutes, resting, and watching the glowing splendor of sunset as reflected in the waters of the stream at his feet. At length he started up and was about to go to the house, where, as he had decided, his very first act would be to ask Elta's forgiveness. The house stood some distance from the river-bank, and was hidden from it by the trees of a young apple orchard. As Winn rose to his feet and cast a lingering glance at the wonderful beauty of the water, he noticed a familiar black object floating amid its splendor of crimsons and gold.

"I wonder how that log got out of the boom?" he said, half aloud. "Why, there's another—and another! The boom must be broken."

Yes, the boom of logs, chained together end to end and stretched completely across the creek to hold in check the thousands of saw-logs that filled the stream farther than the eye could see, had parted near the opposite bank. The end thus loosened had swung down-stream a little way, and there caught on a snag formed of a huge, half-submerged root. It might hold on there indefinitely, or it might get loose at any moment, swing wide open, and set free the imprisoned wealth of logs behind it. As it was, they were beginning to slip through the narrow opening, and those that had attracted Winn's attention were sliding downstream as stealthily as so many escaped convicts.

The boy's first impulse was to run towards the house, calling his father and the mill-hands as he went. His second, and the one upon which he acted, was to mend the broken boom and capture the truant logs himself. "There is no need of troubling father, and I can do it alone better than any number of those clumsy mill-hands," he thought. "Besides, there is no time to spare; for if the boom once lets go of that snag, we shall lose half the logs behind it."

Thus thinking, Winn ran around the mill and sprang aboard the raft that lay just below it. Glancing about for a stout rope, his eye lighted on the line by which the raft was made fast to a tree. "The very thing!" he exclaimed. "While it's aground here the raft doesn't need a cable any more than I need a check-rein, and I told father so. He said there wasn't any harm in taking a precaution, and that the water might rise unexpectedly. As if there was a chance of it! There hasn't been any rain for two months, and isn't likely to be any for another yet to come."

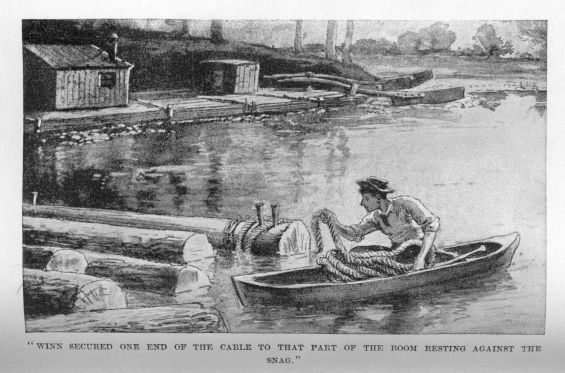

While these thoughts were spinning through the boy's brain, he was casting loose the cable at both ends and stowing it in his own little dugout that was moored to the outer side of the raft. Then with strong deep strokes he paddled swiftly upstream towards the broken boom. After fifteen minutes of hard work he had secured one end of the cable to that part of the boom resting against the snag, carried the other to and around a tree on the bank, back again to the boom, and then to the inshore end of the broken chain. Thus he not only secured the boom against opening any wider, but closed the exit already made.

"That's as good a job as any of them could have done," he remarked to himself, regarding his work through the gathering gloom with great satisfaction. "Now for the fellows that got away."

It was a much harder task to capture and tow back those three truant logs than it had been to repair the boom. It was such hard work, and the darkness added so much to its difficulties, that almost any other boy would have given it up in despair, and allowed the three logs to escape. But Winn Caspar was not inclined to give up anything he had once undertaken. Having determined to do a certain thing, he would stick to it "like a dog to a root," as one of the mill-hands had said of him. So those logs had to go back inside of that boom, because Winn had made up his mind that they should; but they went so reluctantly, and gave him so much trouble, that it was long after dark and some hours past supper-time before the job was completed.

When Winn at length returned to the raft he was wet, tired, and hungry, though very proud of his accomplished task. He was shivering too, now that his violent exertions were ended, for the sky had become overcast, and a chill wind was moaning through the pine-trees.

"I wonder if I can't find something to eat here?" he said to himself. "I'm good and hungry, that's a fact, and they must have had supper up at the house long ago." Entering the "shanty," and feeling carefully about, the boy at length found matches and lighted a lamp.

Hello! There was plenty to eat; in fact, there was a regular spread at one end of the table, with plate, cup and saucer, knife, fork, and napkin, all neatly arranged as though he were expected. "What does it mean?" thought Winn; and then his eye fell on a bit of folded paper lying in the plate. It was a note which read as follows:

"DEAR BROTHER,—As you didn't come home to supper, I thought perhaps you were going to spend the night on the raft, and so brought yours down here. You can heat the tea on the stove. I'm awfully sorry I said anything to make you feel badly. Please forget it, and forgive your loving sister,——ELTA."

"Bless her dear heart!" cried the boy. "She is the best sister in the world. The idea of her asking my forgiveness, when it is I who should ask hers. And I will ask it, too, the very minute I see her; for I shall never be happy until we have kissed and made up, as we used to say when we were young ones. I guess, though, I'll eat the supper she has brought me first. And that's a good idea about heating the tea, too. I can get dry by the stove at the same time. I'll have a chance to see Elta before bedtime, and she'd feel badly if I didn't eat her supper anyway."

All of which goes to show how very little we know of what even the immediate future may bring forth, and that if we put off for a single hour doing that which ought to be done at once, what a likelihood there is that we may never have a chance to do it.

Acting upon the suggestion contained in Elta's note, Winn lighted a fire in the galley stove, and was soon enjoying its cheery warmth. When the tea was heated, he ate heartily of the supper so thoughtfully provided by the dear girl, and his heart grew very tender as he thought of her and of her unwearying love for him. "I ought to go and find her this very minute," he said to himself; "but I must get dry first, and there probably isn't any fire up at the house."

To while away the few minutes that he intended remaining on the raft, Winn got one of the books of exploration from a shelf in the little after-room, and was quickly buried in the heart of an African forest. Completely lost to his surroundings, and absorbed in tales of the wild beasts and wilder men of the Dark Continent, the boy read on and on until the failing light warned him that his lamp was about to go out for want of oil.

He yawned as he finally closed the book. "My! how sleepy I am, and how late it must be," he said. "How the wind howls, too! It sounds as if we were going to have a storm. I only hope it will bring plenty of rain and high-water. Then good-bye to home, and hurrah for the great river!"

By this chain of thought Winn was again reminded of Elta, and of the forgiveness he had meant to secure from her that evening. "It is too late now, though," he said to himself. "She must have gone to bed long ago, and I guess I might as well do the same; but I'll see her the very first thing in the morning."

With this the tired boy blew out the expiring flame of his lamp, and tumbled into his bunk, where in another minute he was as sound asleep as ever in his life.

In the mean time the high-water for which he hoped so earnestly was much nearer at hand than either he or any one else supposed. The storm now howling through the pines had been raging for hours about the head-waters of the creek, and the deluge of rain by which it was accompanied was sweeping steadily down-stream towards the great river. Even as Winn sat by the stove reading, the first of the swelling waters began to rise along the sides of the raft, and by the time the storm broke overhead the Venture was very nearly afloat.

Although Winn slept too soundly to be disturbed by either wind or rain, the storm awoke Major Caspar, who listened for some time to this announcement that the hour for setting forth on his long-projected journey was at hand. He had no anxiety for the safety of the raft, for he remembered the stout cable by which he had secured it, and congratulated himself upon the precaution thus taken. "Besides, Winn is aboard," he reflected, "and he is almost certain to rouse us all with the joyful news the minute he finds that the raft is afloat." Thus reassuring himself, the Major turned over and went comfortably to sleep.

Elta knew nothing of the storm until morning, but hearing the rain the moment she awoke, she too recognized it as the signal for the Venture's speedy departure. From her window she had heretofore been able to see one corner of the raft; but now, peering out through the driving rain that caused the forest depths to appear blue and dim, she could not discover it. With a slight feeling of uneasiness, she hastily dressed, and went to Winn's door. There was no answer to her knock. She peeped in. Winn was not there, nor had the bed been occupied.

"He did spend the night on the raft, then, and so of course it is all right," thought the girl, greatly relieved at this discovery. "The Venture must be afloat, though. I wonder if father knows it?"

Just then Major Caspar appeared, evidently prepared to face the storm.

"Well, little daughter," he said, "high-water has come at last, and the time of our departure is at hand. I am going down to see what Winn thinks of it."

"Oh, can't I go with you, papa? I should dearly love to!" cried Elta.

"Well, I don't know," hesitated the Major. "I suppose you might if you were rigged for it."

This permission was sufficient, and the active girl bounded away full of glee at the prospect of a battle with the storm, and of surprising Winn on the raft. Three minutes later she reappeared, clad in rubber boots and a water-proof cloak, the hood of which, drawn over her head, framed her face in the most bewitching manner.

The Major attempted to protect her still further with a large umbrella; but they had hardly left the house before a savage gust swooped down and gleefully rendered it useless by turning it inside out. Casting the umbrella aside, the Major clasped Elta's hand firmly in his. Then with bowed heads the two pushed steadily on towards the river-bank, while the wind scattered bits of their merry laughter far and wide.

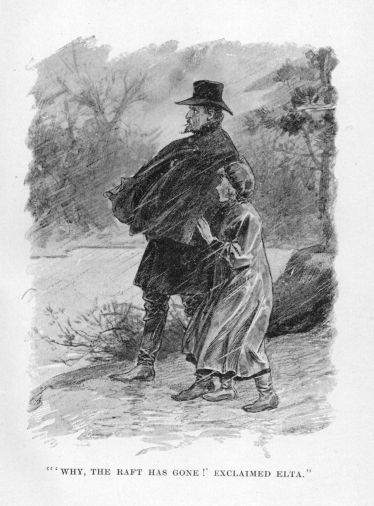

It took them but a few minutes to reach the little stream, when their laughter was suddenly silenced. There was the place where the Venture had been put together, there was the tree to which it had been so securely moored; but the raft that had grown into being and become a familiar sight at that point no longer occupied it, nor was it anywhere to be seen. Only a flood of turbid waters, fully two feet higher than they had been the evening before, swept over the spot, and seemed to beckon mockingly towards the great river.

"Why, the raft has gone!" exclaimed Elta, in a dismayed voice.

"It certainly has," answered the Major, grimly; "and as it cannot possibly have floated up-stream, it must have gone towards the Mississippi. I only hope that Winn managed in some way to check and hold it before it reached the big water; otherwise we may have a merry hunt for it."

While he spoke they had been hurrying to a point a short distance down-stream, around which the creek made a bend. From here they could command a view of half a mile of its course, and somewhere along this stretch of water they hoped to see the raft safely moored. They were, however, doomed to disappointment; for as far as the eye could see there was no sign of the missing craft. Full of conjectures and forebodings of evil they reluctantly turned back towards the house.

The mill-hands, some of whom were to have formed the crew of the Venture, had already discovered that it was gone. Now they were gathered at the house awaiting the Major's orders, and eagerly discussing the situation.

Mrs. Caspar, full of anxiety, met her husband and daughter at the open door, where she stood, regardless of the driving rain.

"Oh, John!" she cried, "where is Winn? What has become of the raft? Do you think anything can have happened to him?"

"Certainly not," answered the Major, reassuringly. "Nothing serious can have befallen the boy on board a craft like that. As to his whereabouts, I propose to go down to the mouth of the creek at once and discover them. That is, just as soon as you can give me a cup of coffee and a bite of breakfast, for it would be foolish to start off without those. But the quicker we can get ready the better. I shall go in the skiff, and take Halma and Jan with me."

Nothing so allays anxiety as the necessity for immediate action, especially when such action is directed towards removing the cause for alarm. So Mrs. Caspar and Elta, in flying about to prepare breakfast for the rescuing party, almost worked themselves into a state of hopeful cheerfulness. It was only after the meal had been hastily eaten, and the Major with his stalwart Swedes had departed, that a reaction came, and the anxious fears reasserted themselves. For hours they could do nothing but discuss the situation, and watch for some one to come with news. Several times during the morning Elta put on her water-proof and went down to the mill. There, she would gaze with troubled eyes at the ever-rising waters, until reminded that her mother needed comforting, when she would return to the house.

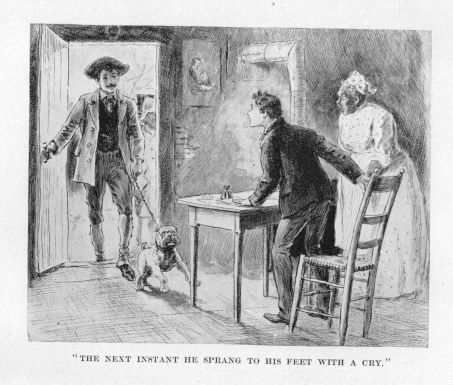

On one of these occasions the girl was surprised to see a saddle-horse, bearing evidences of a hard journey, standing at the hitching-post near the front door. But this first surprise was as nothing to the amazement with which she beheld her mother clasped in the arms of a strange young man who was so bespattered with mud that his features were hardly recognizable. Mrs. Caspar was laughing and crying at the same time, while both she and the young man were talking at once. Near them, and regarding this tableau with the utmost gravity, was a powerful-looking bull-dog, who would evidently be pure white when washed.

For a full minute Elta stood in the doorway gazing wonderingly at this strange scene. Then her mother caught sight of the girl's wide-eyed bewilderment, and burst into a fit of laughter that was almost hysterical.

"It's your uncle William!" she cried, as soon as she could command her voice. "My little brother Billy, whom I haven't seen for twelve years, and he has just come from California. Give him a kiss, dear, and tell him how very glad we are to see him."

Then Elta was in turn embraced by the mud-bespattered young man, who gravely announced that he should never have recognized her.

"No wonder, for she was only a baby when you last saw her!" exclaimed Mrs. Caspar; "and I'm sure I should never have recognized you but for your voice. I don't know how you look even now, and I sha'n't until you wash your face."

"What's the matter with my face? Is it dirty?" asked the young man.

For answer Mrs. Caspar led him in front of a mirror.

"Well, I should say it was dirty! In fact, dirty is no name at all for it!" he laughed. "I believe I look about as bad as Binney Gibbs[1] did when he covered himself with 'mud and glory' at the same time, or rather when his mule did it for him."

"Who is Binney Gibbs?" asked both Mrs. Caspar and Elta.

"Binney? Why, he is a young fellow, about Winn's age, who went across the plains with me a year ago. By-the-way, where is Winn? I want to see the boy. And where is the Major?"

Then, as Mrs. Caspar explained the absence of her husband and son, all her anxieties returned, so that before she finished her face again wore a very sober and troubled expression.

"So that is the situation, is it?" remarked the new-comer, reflectively. "I see that Winn is not behind his age in getting into scrapes. He reminds me of another young fellow who went campmates with me on the plains, Glen Matherson—no, Eddy. No; come to think of it, his name is Elting. Well, any way, he had just such a habit of getting into all sorts of messes; but he always came out of each one bright and smiling, right side up with care, and ready for the next."

"He had names enough, whoever he was," said Elta, a little coldly; for it seemed to her that this flippant young uncle was rather inclined to disparage her own dear brother. "Yes, he certainly had names to spare; but if he was half as well able to take care of himself as our Winn is, no one ever had an excuse for worrying about him."

"No, indeed!" broke in the young man, eagerly; "but I tell you he was— Why, you just ought to have seen him when—"

"Here comes father!" cried Elta, joyfully, running to throw open the door as she spoke.

[1] See Campmates, by the same Author.

It needed but a glance at Major Caspar's face, as, dripping and weary, he entered the house, to show that his search for the raft had been fruitless. His wife's mother-instinct translated his expression at once, and the quick tears started to her eyes as she exclaimed,

"My boy! What has happened to him?"

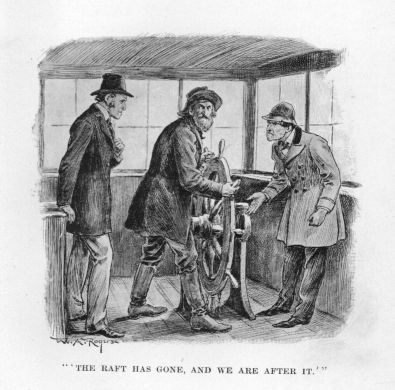

"Nothing serious, you may rest assured, my dear," replied the Major. "I have not seen him; but I have heard of the raft, and there is no question as to its safety. We reached the mouth of the creek without discovering a trace of it. Then we went down the river as far as the Elbow, where we waited in the slack-water to hail up-bound steamboats. The first had seen nothing of the raft; but the second, one of the 'Diamond Jo' boats, reported that they had seen such a raft—one with three shanties on it—at daybreak, in the 'Slant Crossing,' ten miles below. If I could have got a down-river boat I should have boarded her and gone in pursuit, sending the men back to tell you what I had done. As we were unable to hail the only one that passed, I gave it up and came back to report progress."

"Oh, I am so glad you did!" cried Mrs. Caspar.

"So am I," said the young stranger, speaking for the first time since the Major's entrance. The latter had glanced curiously at him once or twice while talking to his wife, but without a gleam of recognition. Now, as he looked inquiringly at him again, Mrs. Caspar exclaimed:

"Why, John, don't you know him? It's William—my own brother William, just come from California."

"So it is," replied the Major, giving the young man a hearty hand-shake—"so it is, William Brackett himself. But, my dear fellow, I must confess I was so far from recognizing you that I thought your name was—"

"'Mud' I reckon," interrupted the other, laughing; "and so it will be before long, if I don't get a chance to clean up. But, Major, by the time both of us are wrung out and dried, and sister has looked up some dinner, I'll be ready to unfold a plan that will make things look as bright for you and Winn and the rest of us as the sun that's breaking away the clouds is going to make the sky directly."

Mrs. Caspar's brother William, "Billy Brackett," as all his friends called him, was a young civil engineer of more than usual ability. He had already gained a larger stock of experience and seen more of his own country than most men of his age, which was about twenty-six. From government work in the East and on the lower Mississippi he had gone to the Kansas Pacific Railway, been detailed to accompany an exploring party across the plains, and, after spending some time on the Pacific coast, had just returned to the Mississippi Valley—out of a job, to be sure, but with the certainty of obtaining one whenever he should want it. From the moment of leaving San Francisco he had intended making the Caspars a visit, and had directed his journey towards their home. In Chicago he had run across an engineering friend named Hobart, who was at that moment regretting the pressure of business that forbade his trying for what promised to be a most profitable contract. It was one for furnishing all the bridge timber to be used in the construction of a new railway through Wisconsin. The bids were to be opened in Madison two days later. Acting upon the impulse of the moment, Billy Brackett hastened to that city and tendered a bid for the contract, which, to his surprise, was accepted.

In doing this the young engineer had counted upon the assistance of his brother-in-law, from whose mill he expected to obtain the timber he had thus contracted to furnish. As the work must be begun immediately, he hurried on to the Major's house with an offer of partnership in this promising undertaking, and arrived as we have seen.

"It's a big thing Major," the young man said in conclusion, after explaining these details at the dinner-table; "and it's not only a big thing in itself, but it will lead to other contracts equally good."

"I should like nothing better than to join you in such an enterprise Billy," replied the Major; "but I don't see how I can go into it just now, with this affair of Winn and the raft on my hands. You say the work must be begun at once?"

"Yes. It really should be started this very day, and it can, if you'll agree to the rest of my plan. You see, I've only told you the half I thought out before getting here. Since then I have added as much more, which is something like this: Suppose you and I change places. You take my horse and go to Madison in the interests of the contract, while Bim and I will take your skiff and start down the river in the interests of Winn and the raft. You know a heap more about getting out bridge timber than I do, while I expect I know more about river rafting than you do. Not that I'm anything of a raftsman," he added, modestly, "but I picked up a good bit of knowledge concerning the river while on that government job down in Arkansas. If you'll only give me the chance, I'll guarantee to find the raft and navigate it to any port you may choose to name—Dubuque, St. Louis, Cairo, New Orleans, or even across the briny—with such a chap as I know your Winn must be for a mate. When we reach our destination we can telegraph for you, and you can arrange the sale of the ship and cargo yourself. As for me, I've had so much of dry land lately that I'm just longing for a home on the rolling deep, the life of a sailor free, and all that sort of thing. What do you say? Isn't my scheme a good one?"

"I declare I believe it is!" exclaimed the Major, who had caught a share of his young kinsman's enthusiasm, and whose face had visibly brightened during the unfolding of his plans. "Not only that, but I believe your companionship with Winn on this river trip, and your example, will be infinitely better for him than mine. I have noticed that young people are much more apt to be influenced by those only a few years older than themselves than they are by persons whose ideas they may regard as antiquated or old-fogyish."

"Oh, papa, how can you say so?" cried Elta, springing up and throwing her arms about his neck. "How can you say that you could ever be an old fogy?"

"Perhaps I'm not, dear, to you," answered the Major, smiling at his daughter's impetuosity; "but to young fellows mingling with the world for the first time nothing pertaining to the past seems of any value as compared with the present or immediate future. Consequently a companion who is near enough of an age to sympathize with the pursuits and feelings of such a one can influence him more strongly than a person whose thoughts are oftener with the past than with the future."

"I can't bear to hear you talk so, husband," said Mrs. Caspar. "As if our Winn wouldn't be more readily influenced by his own father and mother than by any one else in the world! At the same time, I think William's plan well worth considering, for I have hated the idea of that raft trip for you. I have dreaded being left alone here with only Elta, too, though I wouldn't say so when I thought there wasn't anything else to be done."

With this unanimous acceptance of the young engineer's plan, it took but a short time to arrange its details, and before dark everything was settled. The Major was to leave for Madison the next morning, while Billy Brackett was to start down the creek that very evening, so as to be ready at daylight to begin his search for the missing raft at the point where it had been last reported. By his own desire he was to go alone in the skiff, except for the companionship of his trusty Bim, who made a point of accompanying his master everywhere. The young man was provided with an open letter from Major Caspar, giving him full authority to take charge of the raft and do with it as he saw fit.

Both Mrs. Caspar and Elta wrote notes to Winn, and gave them to Billy Brackett to deliver. The major also wrote a line of introduction to an old soldier who had been his most devoted follower during the war. He was now living with a married niece near Dubuque, Iowa, and might possibly prove of assistance during the search for the raft.

Thus equipped, provided with a stock of provisions, and a minute description of both the raft and of Winn, whom he did not hope to recognize, the young engineer and his four-footed companion set forth soon after supper on their search for the missing boy. An hour later they too were being swept southward by the resistless current of the great river.

When Winn Caspar turned into his comfortable bunk aboard the raft on the night of the storm, it never once occurred to him that the Venture might float before morning. She never had floated, and she seemed so hard and fast aground that he imagined a rise of several feet of water would be necessary to move her. It had not yet rained where he was, and the thought that it might be raining higher up the stream did not enter his mind. So he went comfortably to bed, and slept like a top for several hours. Finally, he was awakened so suddenly that he sprang from the bunk, and by the time his eyes were fairly opened, was standing in the middle of the floor listening to a strange creaking and scratching on the roof above his head. It had aroused him, and now as he listened to it, and tried in vain to catch a single gleam of light through the intense darkness, it was so incomprehensible and uncanny, that brave boy as he was, he felt shivers creeping over his arms and back.

Could the sounds be made by an animal? Winn knew there were wild-cats and an occasional panther in the forests bordering the creek. If it was caused by wild-cats there must be at least a dozen of them, and he had never heard of as many as that together. Besides, wild-cats wouldn't make such sounds. They might spit and snarl; but certainly no one had ever heard them squeak and groan. All at once there came a great swishing overhead and then all was still, save for the howling of the wind and the roar of a deluge of rain which Winn now heard for the first time.

The boy felt his way into the forward room and opened the door to look out, but was greeted by such a fierce rush of wind and rain that he was thankful for the strength that enabled him to close it again. Mingled with the other sounds of the storm, Winn now began to distinguish that of waves plashing on the deck of the raft. Certainly his surroundings had undergone some extraordinary change since he turned in for the night, but what it was passed the boy's comprehension.

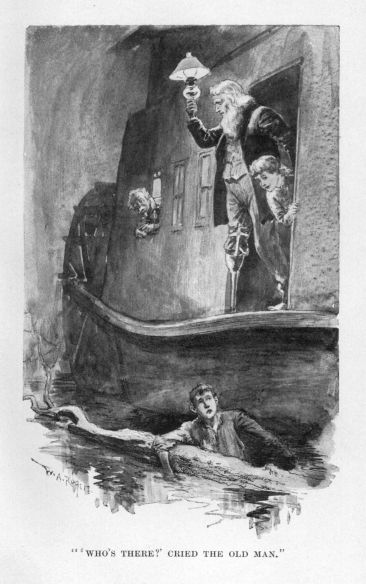

After a long search he found a box of matches and lighted the lamp, forgetting that all its oil had been exhausted the evening before. It burned for a few minutes with a sickly flame, and then went out. Even that feeble light had been a comfort. It had showed him that everything was still all right inside the "shanty," besides enabling him to find and put on the clothes that he had hung near the stove to dry. As he finished dressing, and was again standing in utter darkness puzzling over his situation, he was nearly paralyzed by a blinding glare of light that suddenly streamed into the window nearest him. It was accompanied by the hoarse roar of steam, a confusion of shoutings, and the loud clangor of bells. Without a thought of the weather, Winn again flung open the door and rushed into the open air. So intense and dazzling was the flood of yellow light, that he seemed to be gazing into the crater of an active volcano. It flashed by as suddenly as it had appeared, and the terrified boy became aware that a big steamboat was slipping swiftly past the raft, but a few feet from it. The bewildering glare had come from her roaring furnaces; and had not their doors been thrown open just when they were, she would have crashed at full speed into the raft, with such consequences as can easily be imagined. As it was she was barely able to sheer off in time, and a score of voices hurled back angry threats at the supposed crew of the raft, whose neglect to show a lantern had so nearly led to death and destruction.

So long as he could detect the faintest twinkle of light from the rapidly receding boat, or hear the measured coughings of her exhausted steam, Winn stood gazing and listening, regardless of the rain that was drenching him to the skin. He was overwhelmed by a realization of his situation. That steamboat had told him as plainly as if she had spoken that the Venture was not only afloat, but had in some way reached the great river, and was drifting with its mighty current. He had no idea of how long he had thus drifted, nor how far he was from home. He only knew that the distance was increasing with each moment, and that until daylight at least he was powerless to help himself.

As he turned towards the door of the "shanty," he stumbled over something, which, by stooping, he discovered to be the branch of a tree. To the keen-witted boy this was like the sight of a printed page.

"That accounts for the noise on the roof that woke me," he said to himself. "The raft was passing under those low branches at the mouth of the creek, and I can't be more than a mile or so from there now."

For an instant the idea of paddling home in his canoe and leaving the raft to its fate flashed across his mind, but it was dismissed as promptly as it had come. "Not much I won't!" he said, aloud. "I've shipped for the voyage, and I'm going to see it through in spite of everything. Besides, it's my own fault that I'm in this fix. If I hadn't carried away that cable this thing never could have happened. What a fool I was! But who would have supposed the water could rise so quickly?"

The thought of his little dugout caused the boy to wonder if it were still attached to the raft where he had made it fast the evening before. Again he ventured outside to look for the canoe, but the darkness was so dense and the violence of the storm so bewildering that, after a narrow escape from stepping overboard, he realized that without a light of some kind the undertaking was too dangerous. "There must be a lantern somewhere," he thought. "Yes, I remember seeing one brought aboard." Finally he discovered it hanging near the stove, and, to his joy, it was full of oil. By its aid his search for the canoe was successful, and he was delighted to find it floating safely alongside, though half full of water, and in danger of being stove against the timbers of the raft by the waves that were breaking on deck. With infinite labor he at length succeeded in hauling the little craft aboard and securing it in a place of safety. Then, though he would gladly have had the comfort of a light in the "shanty," the thought of his recent narrow escape warned him to guard against another similar danger by running the lantern to the top of the signal-pole, and leaving it there as a beacon.

He could do nothing more; and so, drenched, chilled, and weary, the lonely lad crept back into the "shanty." How dreary it was to be its sole occupant! If he only had some one to talk, plan, and consult with! He felt so helpless and insignificant there in the dark, drifting down the great river on a raft that, without help, he was as incapable of managing as a baby. What ought he to do? What should he do? It was so hard to think without putting his thoughts into words. Even Elta's presence and counsel would be a comfort, and the boy laughed bitterly to recall how often he had treated the dear sister's practical common-sense with contempt because she was only a girl. Now how gladly would he listen to her advice! It was pretty evident that his self-conceit had received a staggering blow, and that self-reliance would be thankful for the backing of another's wisdom.

As Winn sat by the table, forlorn and shivering, it suddenly occurred to him that there was no reason why he should not have a fire. There was plenty of dry wood. How stupid he had been not to think of it before! Acting upon this idea, he quickly had a cheerful blaze snapping and crackling in the little stove, which soon began to diffuse a welcome warmth throughout the room. By a glance at his watch—a small silver one that had been his father's when he was a boy—Winn found the night to be nearly gone. He was greatly comforted by the thought that in less than two hours daylight would reveal his situation and give him a chance to do something. Still, the lonely waiting was very tedious, the boy was weary, and the warmth of the fire made him sleepy. At first he struggled against the overpowering drowsiness, but finally he yielded to it, and, with his head sunk on his folded arms, which rested on the table, was soon buried in a slumber as profound as that of the earlier night.

At daylight the unguided raft was seen in the "Slant Crossing" by the crew of an up-bound steamboat, and they wondered at the absence of all signs of life aboard it. Every now and then the drifting mass of timber touched on some sand-bar or reef, but the current always swung it round, so that it slid off and resumed its erratic voyage. At length, after floating swiftly and truly down a long straight chute, the Venture was seized by an eddy at its foot, revolved slowly several times, and then reluctantly dragged into a false channel on the western side of a long, heavily-timbered island. Half-way down its length the raft "saddle-bagged," as the river men say, or floated broadside on, against a submerged rock. It struck fairly amidship, and there it hung, forming a barrier, around the ends of which the hurrying waters laughed and gurgled merrily.

With the shock of the striking Winn awoke, straightened himself, and rubbed his eyes, wondering vaguely where he was and what had happened.

After emerging from the "shanty," it did not take the solitary occupant of the raft long to discover the nature of his new predicament. The water was sufficiently clear for him to make out an indistinct outline of the rock on which the raft was hung, and as the rain was still falling, he quickly regained the shelter of the "shanty," there to consider the situation. It did not take him long to make up his mind that this was a case in which assistance was absolutely necessary, and that he must either wait for it to come to him or go in search of it. First of all, though, he must have something to eat. He had no need to look at his watch to discover that it was breakfast-time. The condition of his appetite told him that.

Now Winn had never learned to cook. He had regarded that as an accomplishment that was well enough for girls to acquire, but one quite beneath the notice of a man. Besides, cooking was easy enough, and any one could do it who had to. It was only necessary to put things into a pot and let them boil, or into an oven to bake. Of course they must be watched and taken from the stove when done, but that was about all there was to cooking. There was a sack of corn-meal in the "shanty," and a jug of maple syrup. A dish of hot mush would be the very thing. Then there was coffee already ground; of course he would have a cup of coffee. So the boy made a roaring fire, found the coffee-pot, set it on the stove, and filled a large saucepan with corn-meal.

"There may be a little too much in there," he thought; "but I can save what I can't eat now for lunch, and then fry it, as mother does."

Having got thus far in his preparations, he took a bucket and went outside for some water from the river. Here he remained for a few minutes to gaze at a distant up-bound steamboat, and wondered why he had not noticed her when she passed the raft. Although the river seemed somewhat narrower than he thought it should be, he had no idea but that he was still in its main channel, and that the land on his left was the Wisconsin shore.

Still wondering how he could have missed seeing, or at least hearing, the steamboat, the boy reentered the "shanty." Thinking of steamboats rather than of cooking, he began to pour water into the saucepan of meal, which at once began to run over. Thus recalled to his duties, he removed half of the wet meal to another pan, filled it with water, and set both pans on the stove. Then he poured a stream of cold water into the coffee-pot, which by this time was almost red-hot. The effect was as distressing as it was unexpected. A cloud of scalding steam rushed up into his face and filled the room, the coffee-pot rolled to the floor with a clatter, and there was such a furious hissing and sputtering that poor Winn dropped his bucket of water and staggered towards the door, fully convinced that he was the victim of a boiler explosion.

When the cloud of steam cleared away, the boy ruefully surveyed the scene of disaster, and wondered what had gone wrong. "I'm sure nothing of the kind ever happened in mother's kitchen," he said to himself. In spite of his smarting face, he determined not to be daunted by this first mishap, but to try again. So he wiped the floor with a table-cloth, drew another bucket of water from the river, and resolved to proceed with the utmost care this time. To his dismay, as he stooped to pick up the coffee-pot, he found that it had neither bottom nor spout, but was a total and useless wreck. "What a leaky old thing it must have been," soliloquized the boy.

Just then his attention was attracted by another hissing sound from the stove and a smell of burning. Two yellow streams were pouring over the sides of the saucepans.

"Hello!" cried Winn, as he seized a spoon and began ladling a portion of the contents from each into a third pan. "How ever did these things get full again? I'm sure I left lots of room in them."

At that moment the contents of all three pans began to burn, and he filled them with water. A few minutes later all three began to bubble over, and he got more pans. Before he was through with that mush, every available inch of space on the stove was covered with pans of it, the disgusted cook was liberally bedaubed with it, and so was the floor. The contents of some of the pans were burned black; others were as weak as gruel; all were lumpy, and all were insipid for want of salt.

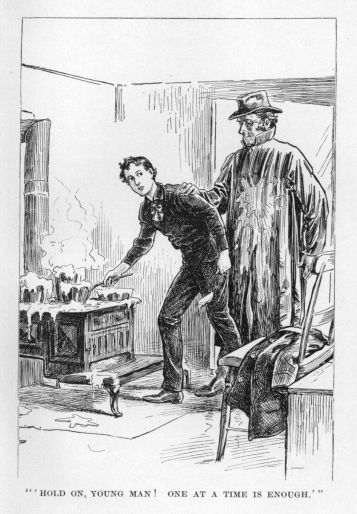

For a moment Winn, hot, cross, and smarting from many scalds and burns, reviewed the results of his first attempt at preparing a meal with a comical expression, in which wrath and disgust were equally blended. Then, yielding to an impulse of anger, he picked up one of the messes and flung it, pan and all, out through the open door. He was stooping to seize the next, which he proposed to treat in a similar manner, when a hand was laid on his shoulder, and he was almost petrified with amazement by hearing a voice exclaim:

"Hold on, young man! One at a time is enough. It's very pleasant to be greeted warmly, but there is such a thing as too warm a reception. I'll allow you didn't see me coming, though if I thought you did, I'd chuck you overboard for that caper."

The speaker, who stood in the doorway striving to remove the mess of sticky mush that had struck him full in the breast and now covered a large portion of his body, including his face, was a man of middle age and respectable appearance, clad in a rubber suit and a slouched hat.

Filled with shame and contrition at this unexpected result of his foolish action, Winn was profuse in his apologies, and picking up the useful table-cloth that had already served him in one emergency, stepped forward with an offer of assistance. The stranger waved him back, and removed the greater part of the mess by taking off his rubber coat. At the same time he said:

"There's no harm done, and worse might have happened. You might have been pitching stove lids, or hot soup, or knives and forks, you know. So, you see, I'm to be congratulated on getting off as well as I have. But where is the boss of this raft, and the crew? How did you happen to run in here out of the channel? You are not alone, are you?"

"Yes, sir," replied Winn. "I'm captain and crew and everything else just at present—excepting cook," he added, hastily, as he noted the stranger's amused glance at the stove and its surroundings.

"Who is cook, then?"

"There isn't any," answered Winn; "and for that reason there isn't any breakfast, nor likely to be any, for I'll starve before I try my hand at it again."

"There seems to be plenty of breakfast, such as it is," said the stranger, gravely, indicating by a glance the many pans of spoiled mush. Then seeing that the boy was really in distress, and not in a joking humor, he added, "But let me help you set things to rights, and then I'll see if I can't show you how to get up some sort of a breakfast. I'm not a regular cook, as perhaps you may guess; but then, again, I am one, in a way, as all we river-traders have to be."

"Are you a river-trader?" asked Winn.

"Yes; and there are three of us. But I'll tell you all about it, and you shall tell me your story after we've had breakfast."

To Winn, the expeditious manner in which his recent culinary disasters were repaired and a simple but well-cooked breakfast was made ready by this stranger was a source of undisguised admiration. Even coffee, clear and strong, was made in a tin can. One edge of the can was bent into the form of a rude spout; then it was filled two-thirds with water, and set on the stove. When the water came to a boil, half a cupful of ground coffee, tied loosely in a bit of clean muslin, was dropped into it, and allowed to boil for three minutes. A kind of biscuit made of flour, water, shortening, baking-powder, and salt, well mixed, and rolled thin, was quickly baked, first on one side and then on the other, in an iron skillet on top of the stove. At the same time a single cupful of corn-meal, well salted, and boiled for half an hour, furnished a large dish of smoking mush. Half a dozen thin slices of bacon broiled on a toaster completed what Winn enthusiastically declared was the very best breakfast he had ever eaten. Still, the boy was so ravenously hungry that it is probable even his own burned and lumpy mixture of corn-meal would not have tasted so bad as it looked.

While he was busy with the breakfast, the stranger, who said his name was Gilder, talked pleasantly on many subjects. At the same time he managed somehow to learn all about Winn and his family, the raft and how it happened to be where it was, without giving a single item of information concerning himself in return.

When Winn finally declared that he could eat no more, Mr. Gilder also pushed back his chair, and said:

"Now, then, for business. First, I must tell you that you are in a very serious predicament. I examined the position of this raft before coming aboard, and arrived at the conclusion that both it and its cargo are in a fair way of becoming a total loss. As soon as the river falls again, which it is likely to do at any time, the raft will probably break in pieces of its own weight. In that case you would lose both it and your wheat. The only plan I can suggest for saving the raft is to lighten it until it floats clear of the rock on which it is hung, by throwing the wheat overboard; or, if you can manage it, land your wheat on the island, where it can remain until you can take it away. Of course the decision as to which of these things you will do rests entirely with yourself; but you must make up your mind quickly, for with this uncertain state of water there isn't an hour to lose."

For a whole minute Winn sat silent, while from the opposite side of the table Mr. Gilder regarded his perplexed countenance with an expression that was not altogether pleasant. Winn, suddenly looking up from his hard thinking, was a bit startled by it; but as it instantly melted into one of smiling sympathy, his confidence in the man remained unbroken. Had he seen Mr. Gilder two hours earlier, instead of one, his opinion of the individual who had just prepared such a capital breakfast, expressed so great friendliness, and now showed him so plainly the unpleasant predicament into which he had fallen, would have been decidedly different.

At that time Mr. Gilder was kneeling beside an opening in the floor of a log-hut, in the centre of the island, and lifting from it a tray of odd-looking but beautifully made tools. The hut was small and rudely constructed. It was surrounded by a dense forest growth, and stood in a tiny clearing from which no road or trail could be seen to lead. All its appointments were of the most primitive description, and yet a single glance into its interior would have impressed one with the belief that its occupants were millionaires. The effect of piles and stacks of greenbacks, enough to form the capital of a city bank or fill the vaults of a sub-treasury, amid such surroundings, would certainly have startled even those accustomed to the handling of great wealth. The bills, all of which were new and crisp, were done up in neat packages, each of which was marked with the number of hundreds or thousands of dollars it contained. In one corner of the room stood a small printing-press of exquisite make. Besides this press, a work-bench, table, and several rude stools, the single room of the hut contained only the piles of greenbacks.

A man sat beside the table counting and sorting a large number of bills, the worn appearance of which showed them to have been in active circulation for some time. This man was small, and had a weazened face devoid of hair except for a pair of bushy, iron-gray eyebrows, beneath which his eyes gleamed as cunningly bright as those of a fox. He answered to the name of Grimshaw; and as he counted bills with the deftness and rapidity of a bank cashier, he also paid a certain amount of attention to the remarks of his companion, who was talking earnestly.

"I tell you what it is, Grim," the other was saying, as he bent over the secret opening in the floor, "it's high time we were moving. This is a first-class location, and we've done well here; but you know as well as I do that our business requires a pretty frequent change of scene, and I'm afraid we've stayed here too long already. One of those mill fellows said only yesterday that we must have collected a powerful lot of stuff by this time, and asked if we weren't about ready to invite him up to inspect and bid on it. I told him we were thinking of putting it into a raft and taking it down-river. Never had such an idea, you know, but the notion just popped into my head, and I'm not sure now but what it's as good a one as we'll strike. What do you think?"

"It'll take a heap of hard work, and more time than I for one want to spare, to build a raft large enough for our purpose," answered Grimshaw. "Still, I don't know as the idea is wholly bad."

"It would take time, that's a fact," answered Mr. Gilder, lifting his tray of tools to the table and proceeding to polish some of them with a bit of buckskin. "And it looks as though time was going to be an object with us shortly. That last letter from Wiley showed that the Chicago folks were beginning to sniff pretty suspiciously in this direction. I've been asked some awkward questions lately, too. Yes, the more I think of it, the more I am convinced that we ought to be getting out of here as quickly as we can make arrangements. We must talk it over with Plater, and come to some decision this very day. He's— Hello! Something's up. Plater was to stay in camp till I got back."

Again came the peculiar, long-drawn whistle that had arrested the attention of the men, and which denoted the approach of a friend. Mr. Gilder stepped to the door and answered it. Then he looked expectantly towards a laurel thicket that formed part of the dense undergrowth surrounding the hut. In a moment the dripping branches were parted near the ground, and a man, emerging from the bushes on his hands and knees, stood up, shook himself like a Newfoundland dog, and advanced towards the open door. He was a large man with long hair and a bushy beard. He was clad in flannel, jeans, and cowhide boots, and was evidently of a different class from Mr. Gilder, who appeared to be a gentleman, and was dressed as one. "What's up, Plater?" asked the latter.

"Big raft, three shanties on it, in false channel, saddle-bagged on the reef pretty nigh abreast of camp. Can't see nobody aboard. Reckon she broke adrift from somewheres while her crew was off on a frolic."

"You don't say so!" cried Mr. Gilder, excitedly. "Perhaps it's the very thing we are most in need of, sent by a special providence to crown our labors with success. I'll go down and have a look at her, while you stay here and help Grim pack up the stuff. We might as well be prepared for a sudden move, and he'll tell you what we have just been talking about."

So Mr. Gilder, donning his rubber coat, a garment that Plater would have scorned to wear, left the clearing through another bushy thicket on the opposite side from that by which his confederate had entered it. An almost undiscernible path led him to the shore of the island that was washed by the main channel of the river. Here he struck into a plainly marked trail that followed the water's edge. In this trail Mr. Gilder walked to the southern end of the island, and up its other side until he reached a comfortable camp that bore signs of long occupancy. It stood high on a cut bank, and just below it a rude boom held a miscellaneous assortment of logs, lumber, and odd wreckage, all of it evidently collected from the stray drift of the great river.

From the edge of the bank, a short distance from this camp, the man commanded a good view of the stranded raft, and for several minutes he stood gazing at it. "There's the very thing to a T, that we want," he said to himself. "Not too big for us to handle, and yet large enough to make it seem an object for us to take it down the river. I can't see what they want of three shanties, though; one ought to be enough for all the crew she needs. Our first move would be to tear down two of them, and lengthen the other; that alone would be a sufficient disguise. We haven't got her yet, though, and she isn't abandoned either, for there's smoke coming from that middle shanty. I reckon the cook must be aboard, and maybe he'll sell the whole outfit for cash, and so give us a clear title to it." Here Mr. Gilder smiled as though the thought was most amusing. "I'll go off and interview him anyway, and I'd better be about it too, for the river is still rising. She won't hang there much longer, and if the fellow found his raft afloat again before a bargain was made he might not come to terms. In that case we should be obliged to take forcible possession, which would be risky. I'm bound to have that raft, though. It is simply a case of necessity, and necessity is in the same fix we are, so far as law is concerned."

While thus thinking, Mr. Gilder had stepped into a light skiff that was moored near the boom, and was pulling towards the stranded raft. He first examined its position, and assured himself that very little labor would be necessary to float it; then he stepped aboard, and very nearly lost his customary self-possession upon the receipt of Winn's warm greeting. He was on the point of returning it in a manner that would have proved most unpleasant for poor Winn, when he discovered that his supposed assailant was only a boy, and that the act was unintentional. It took the shrewd man but a few minutes to discover the exact state of affairs aboard the raft, and to form a plan for gaining peaceful, if not altogether lawful, possession of it. This plan he began to carry out by the false statement of the situation made to Winn at the conclusion of the last chapter. This beginning was not made, however, until he had first gained the lad's confidence by a deed of kindness.

When Winn looked up from his hard thinking he said, "I hate the thought of throwing the wheat overboard, even to save the raft. There are two thousand bushels of it, and I know my father expects to get at least fifty cents a bushel. So it would seem like throwing a thousand dollars into the river. Then, again, I don't see how it will be possible to land it, and so lighten the raft. It would take me a month to do it alone with my canoe. Besides, father is sure to set out on a hunt for the raft the moment he finds it is gone, and so is likely to come along most any time."

"All the greater need for haste," thought Mr. Gilder; but aloud he said, "That is very true, but in the mean time your raft will probably break up, and your wheat be spilled in the river anyway. Now suppose you agree to pay me and my partners a hundred dollars to get the wheat ashore for you and reload it after the raft floats."

"I haven't a cent of money with me," replied Winn.

"That's bad," said the other, reflectively. "It's awkward to travel without money. But I'll tell you what we'll do. I hate to see a decent young fellow like you in such a fix, and I'm willing to take a risk to help him out of it. Suppose I buy your wheat? I told you that I and my partners were river traders. To be sure, our business is mostly in logs, lumber, and the like; but I don't mind taking an occasional flyer in wheat, provided they are willing. You say your father expects to get fifty cents a bushel for this wheat. Now I'll give you forty-five cents a bushel for it; that is, if my partners agree. That will leave five cents a bushel to pay us for landing it, transferring it to some other craft, and getting your raft afloat. What do you say?"

"I wish I could ask father about it," hesitated Winn, to whom, under the circumstances as he supposed them to exist, the offer seemed very tempting.

"Oh, well," sneered Mr. Gilder, "if you are not man enough now to act upon your own responsibility in such an emergency, you never will be. So the sooner you get home again and tie up to your mother's apron-string the sooner you'll be where you belong."

The taunt was as well worn as it was cruel, and should have given Winn an insight into the true character of his new acquaintance; but on a boy so proud of his ability to decide for himself, and so ignorant of the ways of the world as this one, it was sufficient to produce the desired effect.

Winn flushed hotly as he answered: "The wheat is my father's, and not mine to sell; but for the sake of saving it as well as the raft, I will let you have it at that price. I must have the cash, though, before you begin to move it."

"Spoken like the man I took you to be," said Mr. Gilder, heartily. "Now we'll go ashore and see my partners. If they agree to the bargain, as no doubt they will, we'll get to work at once, and have your raft afloat again in no time."

When Winn and his new acquaintance stepped outside of the "shanty," it did not seem to the boy that the river was falling, or that the raft was in a particularly dangerous position. He would have liked to examine more closely into its condition, but his companion so occupied his attention by describing the manner in which he proposed to remove the wheat, and so hurried him into the waiting skiff, that he had no opportunity to do so.

The "river-traders'" camp was not visible from the raft, nor did Mr. Gilder, who handled the oars, head the skiff in its direction. He rowed diagonally up-stream instead, so as to land at some distance above it. There he asked Winn to wait a few minutes until he should discover in which direction his partners had gone. He explained that one of them had been left in camp at a considerable distance from that point, while he and the third had been rowing along the shore of the island in opposite directions, searching for drift-logs. Thus he alone had discovered the stranded raft. Now he wished to bring them to that point, that they might see it for themselves before he explained the proposed wheat deal. With this Mr. Gilder plunged directly into the tall timber, leaving Winn alone on the river-bank.

It was fully fifteen minutes before the man returned to the waiting lad, and he not only looked heated but anxious.

"I can't think what has become of those fellows!" he exclaimed, breathlessly, as he wiped the moisture from his forehead with a cambric handkerchief. "I've been clear to camp without finding a trace of either of them. Now there is only one thing left for us to do in order to get them here quickly. You and I must start around the island in opposite directions, because if we went together we might follow them round and round like a kitten chasing its tail. If you meet them, bring them back here, and I will do the same. If you don't meet them, keep on until you are half-way down the other side of the island, or exactly opposite this point; then strike directly into the timber, and so make a short-cut back here. In that way you will reach this place again as soon as I, for the island isn't more than three hundred yards wide just here. Be spry, now, and remember that the safety of your raft depends largely upon the promptness with which we get those other fellows here."

With this Mr. Gilder began to walk rapidly down the shore in the direction he had chosen. Carried away by the man's impetuosity, Winn did not hesitate to obey his instructions, but started at once in the opposite direction. Mr. Gilder, noting this by a backward glance over his shoulder, instantly halted and concealed himself behind a large tree-trunk. From here he peered at the retreating figure of the boy until it was no longer visible. Then he gave vent to the same peculiar whistle with which Plater had announced his own approach to the log-hut in the woods. The sound was immediately answered from no great distance, whereupon Mr. Gilder hastened in that direction. A minute later he returned, bringing a coil of stout rope, one end of which he made fast to a tree on the bank. At the same time both Grimshaw and Plater appeared, each bearing a large package securely wrapped in canvas on his shoulder.

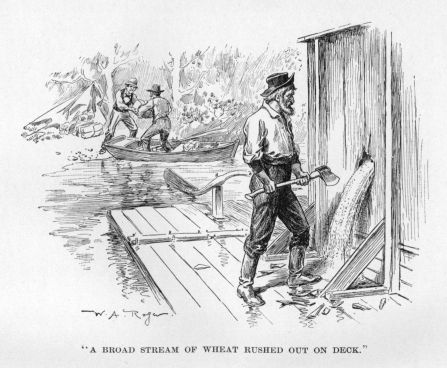

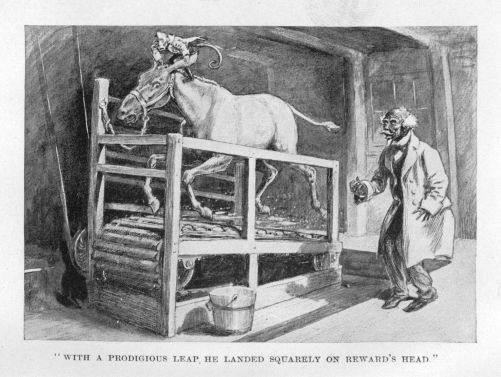

All three men entered the skiff and pulled out to the raft, carrying the loose end of the rope with them. Mr. Gilder and Grimshaw quickly returned to the land, leaving the burly Plater to make a vigorous attack with an axe against the sides of one of the wheat bins. He soon splintered and tore off a board, leaving an aperture through which a broad stream of wheat rushed out on the deck of the raft. This Plater began to shovel overboard, working with furious energy, as though combating a hated enemy. In ten minutes both bins were empty, and so much of the wheat had gone into the ever-rising waters that the raft, which had been on the point of floating when Plater began his operations, now did so, and swung in close to the bank at the end of its new cable.

In the mean time the other men had brought several skiff-loads of their peculiar merchandise to the raft, and now it took but a few minutes to transfer what remained on the bank directly to it. Even the tent, which had been hastily torn down, together with a portion of their camp outfit, was tossed aboard, and within fifteen minutes from the time of Winn's departure the Venture, with its new crew at the sweeps, was moving slowly out from the island, and gathering impetus from the current for a continuance of its eventful voyage.

Without a suspicion that the gentlemanly stranger who had so kindly smoothed away his culinary difficulties, and, while apparently willing to assist him, was also anxious to make a good bargain for himself, was anything but what he appeared to be, Winn made his way briskly towards the head of the island. It was only after rounding it and starting down the opposite side without seeing a sign of those whom he sought that he began to have misgivings.

"I wonder if it is all right?" he said to himself. "What could be the man's object in telling me that the raft was in a dangerous position if she isn't? I declare I don't believe she is, though! She didn't look it when I left, and I do believe the river is still rising. I wonder if I haven't done a foolish thing in leaving the raft? If I have, the best thing to do now is to get back as quickly as possible."

By this time the boy had worked himself into a fever of apprehension, and, remembering what he had been told concerning the narrowness of the island, he determined to make a short-cut across it. This was exactly what the far-sighted Mr. Gilder had anticipated, and Winn fell an easy victim to his artfully planned trap. For nearly an hour the boy, versed in wood-craft as he was, wandered and struggled through the dense undergrowth of that island forest. Suddenly, as he burst his way through a thicket, he was confronted by the log-hut so lately occupied by the "river-traders." Winn shouted as he approached it; but, of course, received no reply. It had the lonely look of a place long deserted, and the boy paused for but a single glance into its uninviting interior. Then, getting his bearings anew by the sun that was beginning to struggle through the clouds, he pushed his way resolutely towards the western side of the island, which, somewhat to his surprise, he reached a few minutes later.

He emerged from the timber at the abandoned camp of the traders; but without stopping to examine it, he ran to the water's edge, and gazed anxiously both up and down stream. There was no sign of the raft nor of any moving object. "It must be farther up, around that point," thought Winn, and he hurried in that direction. From one point to another he thus pursued his anxious way until the head of the island was once more in sight. Then he knew that he must have passed the place where the raft had been, and that it was gone.

As a realizing sense of how he had been duped and of his present situation flashed through his mind, the poor boy sat down on a log, too bewildered to act, or even to think.

Winn Caspar was indeed unhappy as he sat on that log and gazed hopelessly out over the sparkling waters, on which the sun was now shining brightly. Although he had explored only a portion of the island, he felt that he was alone on it. But that was by no means the worst of the situation. The raft in which he had taken so much pride, his father's raft upon which so much depended, the raft on which he had expected to float out into the great world, was gone, and he was powerless to follow it. All through his own fault, too! This thought was the hardest to bear. Why, even Elta would have known better. Of course she would. Any one but he would, and she was wiser than almost any one he knew. How dearly he loved this wise little sister, and to think that he had parted with her in anger! When was that? Only last evening! Impossible! It must have been weeks ago. It wasn't, though! It was only a few hours ago, and his father had hardly had time to come and look for him yet. Perhaps he was even now on his way down the river, and might be passing on the other side of the island.

With this thought the boy sprang to his feet, and hurrying to the head of the island, eagerly scanned the waters of the main channel. There was nothing in sight, not even a skiff or a canoe. "Even my dugout is gone," thought Winn, with a fresh pang, for he was very fond of the little craft that was all his own. Then he wondered how he should attract his father's attention, and decided to build a fire, with the hope that Major Caspar might come to it to make inquiries, and thus effect his rescue.

Having a definite object to work for cheered the boy somewhat, and his heart grew sensibly lighter as he began to collect wood for his fire. But how should he light it? He had no matches. For a moment this new difficulty seemed insurmountable; then he remembered having seen the smouldering remains of a fire at the abandoned camp on the other side of the island. He must go back to it at once.

Hurrying back around the head of the island, Winn reached the place just in time to find a few embers still glowing faintly, and after whittling a handful of shavings, he succeeded, by a great expenditure of breath, in coaxing a tiny flame into life. Very carefully he piled on dry chips, and then larger sticks, until finally he had a fire warranted to live through a rain-storm. Now for another on the opposite side of the island!

He could not carry lighted sticks the way he had come. It was too far. He thought he could get them safely across the island, though, if he only knew the most direct path. He would first discover this and then return for his fire. Quite early in the search he stumbled across a very narrow trail that seemed to lead in the right direction. By following it he came once more to the deserted log-hut in the forest, but search through the little clearing as he might, he could not see that it went any farther.

Taking his bearings, after deciding to open a trail of his own from there to the river, the boy attacked a thicket on the eastern side of the clearing with his jack-knife. A few minutes of cutting carried him through it, and, to his amazement, he found himself again in an unmistakable trail. It was narrow and indistinct, but it was none the less a trail, leading in the right direction, and the boy was woodman enough to follow it without hesitation to the river-bank. A steamboat was passing the island, but though Winn waved frantically to it and shouted himself hoarse, no attention was paid to him. With a heavy heart he watched it out of sight, and then began another collection of wood for his signal-fire.