The Project Gutenberg EBook of Oscar Wilde, by Leonard Cresswell Ingleby This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Oscar Wilde Author: Leonard Cresswell Ingleby Release Date: December 9, 2011 [EBook #38251] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OSCAR WILDE *** Produced by Mark C. Orton, Cathy Maxam and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

This e-book contains one phrase in ancient Greek, which may not display properly depending on the fonts the user has installed. Hover the mouse over the Greek phrase to view a transliteration, e.g., λογος.

Blank pages have been removed from the text. Some page numbers are missing as a result.

Inconsistencies in the author's use of hyphens and accent marks have been left unchanged, as in the original text. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected without comment. One example of a typographical error is on page 144 where the word "miuutes" was corrected to "minutes". In cases other than obvious typographical errors, the author's spelling has been left unchanged from the original text with the following three exceptions:

1. Page 126 the word "worldings" was changed to "worldlings" in the phrase: "... guests are all mere worldlings...."

2. Page 262 the quoted phrase: "Fait vour quelle sera votre votre maturité" was changed to: "Fait voir quelle sera votre maturité" which is the correct wording from the poem "À Théodore de Banville" by Charles Baudelaire.

3. Page 317 the name "Bazil" was changed to "Basil" in the phrase: "Basil Hallward's studio" to correspond with the author's other spellings of the name Basil Hallward.

Two items in the index, which were out of alphabetical order ("De Profundis—Biblical influence" and "Shaw, G. B.") were placed in correct alphabetical order in this version.

THIRD EDITION

THE LIFE OF

OSCAR WILDE

WITH A CHAPTER CONTRIBUTED BY

THE PRISON WARDER WHO HELD

THIS UNHAPPY MAN IN GAOL

Very fully Illustrated and with Photogravure

Frontispiece, and a Biography

By

Robert Harborough Sherard

Demy 8vo, Cloth gilt

Also a limited edition de luxe

OSCAR WILDE,

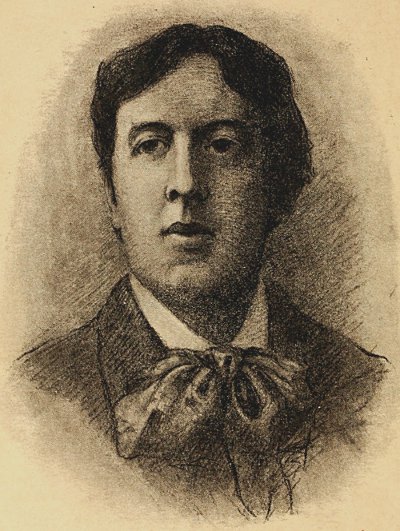

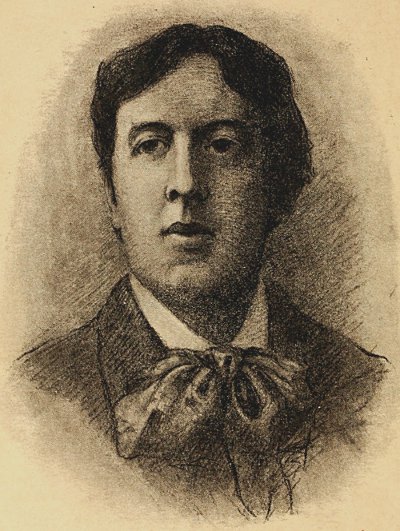

From a Crayon Portrait by S. Wray.

BY

LEONARD CRESSWELL INGLEBY

LONDON

T. WERNER LAURIE

NEW YORK

MITCHELL KENNERLEY

MCMVII

| PAGE | |

| PART I | |

| Oscar Wilde: The Man | 3 |

| PART II | |

| The Modern Playwright | |

| The Dramatist | 95 |

| "Lady Windermere's Fan" | 104 |

| "A Woman Of No Importance" | 119 |

| "The Ideal Husband" | 129 |

| "The Importance Of Being Earnest" | 149 |

| PART III | |

| The Romantic Dramas | |

| "Salomé" | 161 |

| "The Duchess of Padua" | 191 |

| "Vera, or the Nihilists" | 207 |

| "The Florentine Tragedy" | 215 |

| "The Woman Covered With Jewels" | 220 |

| PART IV | |

| The Writer of Fairy Stories | |

| The Fairy Stories | 227 |

| PART V[Pg viii] | |

| The Poet | |

| Poems | 245 |

| PART VI | |

| The Fiction Writer | |

| Fiction | 301 |

| PART VII | |

| The Philosophy of Beauty | 331 |

| PART VIII | |

| De Profundis | 359 |

| INDEX | 397 |

OSCAR WILDE: THE MAN

THE MAN

The συνετοι, the connoisseurs, always recognised the genius of Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde from the very first moment when he began to write. For many years ordinary people to whom literature and literary affairs were not of, at anyrate, absorbing interest only knew of Oscar Wilde by his extravagances and poses.

Then it happened that Wilde turned his powers in the direction of the stage and achieved a swift and brilliant success. The English public then began to realise that here was an unusually brilliant man, and the extraordinary genius of the subject of this work would have certainly been universally recognised in a few more years, when the shocking scandals associated with his name occurred and Oscar Wilde disappeared into oblivion.

A great change gradually took place in public opinion. Little by little the feeling of prejudice against the work of Oscar Wilde began to die away. The man himself was dead. He had expiated his crimes by a prolonged agony of the most hideous suffering and disgrace, and[Pg 4] people began to wonder if his writings were in any way associated with the dark side of his life and character, or whether they might not, after all, be beautiful, pure, and treasures of the literature of our time. The four comedies of Manners, "Lady Windermere's Fan," "The Ideal Husband," "A Woman Of No Importance," "The Importance Of Being Earnest," everyone had seen and laughed at. They were certainly absolutely without offence. It was gradually seen that because a house was built by an architect of an immoral private life that did not necessarily invalidate it as a residence, that if Stephenson had ended his life upon the gallows people would still find railways convenient and necessary. The truth gradually dawned that Wilde had never in his life written a line that was immoral or impure, and that, in short, the criminal side of him was only a part of his complex nature, horribly disastrous for himself and his personal life, but absolutely without influence upon his work.

Art and his aberration never mingled or overlapped. Everybody began to realise the fact.

Opinion was also being quietly moulded from within by a band of literary and artistic people, some of them friends of the late author, others knowing him simply through his work.

The public began to ask for Wilde's books and found it almost impossible to obtain them,[Pg 5] for the "Ballad of Reading Gaol," published while its author was still alive, had not stimulated any general demand for other works.

It was after Oscar Wilde's death that his friends and admirers were able to set to work at their endeavours to rehabilitate him as artist in the mind of general prejudice. Books and monographs were written about Wilde in English, French, and German. He was quoted in the leading Continental reviews. His play "Salomé" met with sudden and stupendous success all over Europe, a famous musician turned it into an opera. A well-known English man of letters, Mr Robert Harborough Sherard, published a final official "Life" of the dead author, and Wilde's own "De Profundis" appeared to startle, sadden, and thrill the whole reading world.

His plays are being revived, and an authoritative and exhaustive edition of his writings is being issued by a leading publishing house.

There is no doubt about it, the most prejudiced and hostile critics must admit it—in a literary sense, as a man of letters with extraordinary genius, Oscar Wilde has come into his own. The time is, therefore, ripe for a work of the present character which endeavours to "appreciate" one of the strangest, saddest, most artistic and powerful brains of modern times. Five years ago such a book as this would probably[Pg 6] have been out of place. When Balzac died Sainte-Beuve prefaced a short critical article of fourteen pages, as follows:—

"A careful study of the famous novelist who has just been taken from us, and whose sudden loss has excited universal interest, would require a whole work, and the time for that, I think, has not yet come. Those sort of moral autopsies cannot be made over a freshly dug grave, especially when he who has been laid in it was full of strength and fertility, and seemed still full of future works and days. All that is possible and fitting in respect of a great contemporary renown at the moment death lays it low is to point out, by means of a few clear-cut lines, the merits, the varied skill, by which it charmed its epoch and acquired influence over it."

When Oscar Wilde died, and before the publication of "De Profundis," various short essays did, as I have stated, make an appearance. A longer work seems called for, and it is that want which the present volume does its best to supply.

"Oscar Wilde: The Man" is the title of the first part of this Appreciation. In Mr Sherard's "The Story of an Unhappy Friendship," as also in his careful and scholarly "Life," the many-sided nature of Oscar Wilde was set forth with all the ability of a brilliant pen. But there is yet room for another, and possibly more detached[Pg 7] point of view, and also a summary of the views of others which will assist the general reader to gain a mental picture of a writer whose works, in a very short time, are certain to have a general, as well as a particular appeal.

The scheme of a work of this nature, which is critical rather than biographical, would nevertheless be incomplete without a personal study.

The study of Wilde's writings cannot fail to be enormously assisted by some knowledge of synetoithe man himself, and how he was regarded by others both before and after his personal disgrace.

Ever since his name was known to the world at all the public view of him has constantly been shifting and changing. There are, however, four principal periods during each of which Wilde was regarded in a totally different way. I have made a careful analysis of each of these periods and collected documentary and other evidence which defines and explains them.

The first period of all—Oscar Wilde himself always spoke of the different phases of his extraordinary career as "periods"—was that of the "Æsthetic movement" as it is generally called, or the æsthetic "craze" as many people prefer to name it still. New movements, whether good or bad in their conception and ultimate result, always excite enmity, hostility, and ridicule. In affairs, in religion, in art, this is an invariable[Pg 8] rule. No pioneer has ever escaped it. England laughed at the first railway, jeered at the volunteer movement and laughed at John Keats in precisely the same fashion as it ridiculed Oscar Wilde and the æsthetic movement.

It is as well to define that movement carefully, for, though marred by innumerable extravagances and still suffering from the inanities of its first disciples, it has nevertheless had a real and permanent influence upon English life. Oscar Wilde was, of course, not the originator of the æsthetic movement. He took upon himself to become its hierophant, and to infuse much that was peculiarly his own into it. The movement was begun by Ruskin, Rossetti, William Morris, Burne-Jones, and a host of others, while it was continued in the delicate and beautiful writings of Walter Pater. But it had always been an eclectic movement, not for the public eye or ear, neither known of nor popular with ordinary people.

Oscar Wilde then began to interest and excite England and America in the true aims and methods of art of all kinds. It shows an absolute ignorance of the late Victorian era to say that the movement was a passing craze. To Oscar Wilde we owe it that people of refined tastes but moderate means can obtain beautiful papers for the walls of their houses at a moderate cost. The cheap and lovely fabrics that we[Pg 9] can buy in Regent Street are spun as a direct consequence of the movement; harmony and delicacy of colour, beauty of curve and line, the whole renaissance of art in our household furniture are mainly due to the writings and lectures of Oscar Wilde.

It is not a crime to love beautiful things, it is not effeminate to care for them. It is to the subject of this appreciation we owe our national change of feeling on such matters.

This, briefly, is what the æsthetic movement was, such are its indubitable results. Let us see, in some instances, how Wilde was regarded in the period when, before his real literary successes, he preached the gospel of Beauty in everyday life.

Let us take a Continental view of Wilde in his first period, the view of a really eminent man, a distinguished scientist and man of letters.

The name of Dr Max Nordau will be familiar to many readers of this book. But, if the book fulfils the purpose for which it was designed, then possibly there will be many readers who will know little or nothing of the distinguished foreign writer. Hard, one-sided, and bitter as his remarks upon Wilde during the æsthetic movement will seem to most of us—seem to me—yet they have the merit of absolute detachment and sincerity. It is as well to insist on this fact in order that my readers may realise exactly such[Pg 10] value as the words may have, no less and no more. The following short account of Dr Max Nordau's position and achievements is taken from that useful dictionary of celebrities, "Who's Who?" for 1907:—

"Nordau, Max Simon, M.D. Paris, Budapesth; Officier d'Académie, France; Commander of the Royal Hellenic Order of the St Saviour; author and physician; President Congress of Zionists; Hon. Mem. of the Greek Acad. of the Parnassos; b. Budapesth, 29th July 1849; y. s. of Gabriel Südfield, Rabbi, Krotoschin, Prussia, and his 2nd wife, b. Nelkin, Riga, Russia. Educ. Royal Gymnasium and Protestant Gymnasium, Budapesth; Royal University, Budapesth; Faculty of Medicine, Paris. Wrote very early for newspapers; travelled for several years all over Europe; practised as a physician for a year and a half, 1878-80, at Budapesth; settled then at Paris, residing there ever since; m. Anna-Elizabeth, 2nd d. of State-councillor Captain Julius Dons, Copenhagen, Denmark; one d. Publications: Paris, Studien und Bilder aus dem wahren Milliardenlande, 1878; Seifenblasen, 1879; Vom Kreml zur Alhambra, 1880; Aus der Zeitungswelt (together with Ferdinand Gross), 1880; Paris under der dritten Republik, 1881; der Krieg der Millionen, 1882; Die conventionellen Lügen der Culturmenschheit, 1883; Ausgewählte Pariser Briefe, 1884; Paradoxe,[Pg 11] 1885; Die Krankheit des Jahrhunderts, 1887; Seelenanalysen, 1891; Gefühlskomödie, 1892; Entartung, 1893; Das Recht zu lieben, 1894; Die Kugel, 1895; Drohnenschlacht, 1896; La funzione sociale dell arte, 1897; Doctor Kohn, 1898; The Drones must Die, 1899: Zeitgenössische Franzosen, 1901; Morganatic, 1904; Mahâ-Rôg, 1905. Recreations: foil-fencing, swimming. Address: 8, Rue Léonie, Paris."

Nearly all the modern manifestations of Art, implies Dr Max Nordau, in "Degeneration," are manifestations of madness. Such a sweeping statement is incredible and has not—nor will it have—many advocates, despite the brilliant special pleading of its originator. In Oscar Wilde's case the aphorism seems particularly misleading for the reason that there may appear to be a considerable amount of truth in it.

That Wilde's social downfall was due to a certain kind of elliptiform insanity is without doubt. Mr Sherard has insisted on this over and over again. He has spent enormous labour in researches into Wilde's ancestry. His view is really a scientific view because it is written by an artist who sees both sides of the question, has a judicial mind, and while capable of appreciating the truths that science teaches us, is further capable of welding them to the psychological truths which the intuition of the artist alone evolves.

A certain definite and partial insanity alone[Pg 12] can explain Wilde's life in certain of its aspects. But when once his pen was in his hand, in his real bright life of literature and art, this hidden thing entirely disappears. Therefore, Dr Max Nordau's study seems to me fundamentally wrong, though extremely interesting and not to be disregarded. To know Oscar Wilde we must know what all sorts of people, whose opinion has weight enough to secure a wide hearing, really thought about him.

The German scientist said:

"The ego-mania of decadentism, its love of the artificial, its aversion to nature, and to all forms of activity and movement, its megalomaniacal contempt for men and its exaggeration of the importance of art, have found their English representative among the 'Æsthetes,' the chief of whom is Oscar Wilde.

"Wilde has done more by his personal eccentricities than by his works. Like Barbey d'Aurevilly, whose rose-coloured silk hats and gold lace cravats are well known, and like his disciple Joséphin Péladan, who walks about in lace frills and satin doublet, Wilde dresses in queer costumes which recall partly the fashions of the Middle Ages, partly the rococo modes. He pretends to have abandoned the dress of the present time because it offends his sense of the beautiful; but this is only a pretext in which probably he himself does not believe. What[Pg 13] really determines his actions is the hysterical craving to be noticed, to occupy the attention of the world with himself, to get talked about. It is asserted that he has walked down Pall Mall in the afternoon dressed in doublet and breeches, with a picturesque biretta on his head, and a sunflower in his hand, the quasi-heraldic symbol of the Æsthetes. This anecdote has been reproduced in all the biographies of Wilde, and I have nowhere seen it denied. But it is a promenade with a sunflower in the hand also inspired by a craving for the beautiful.

"Phrasemakers are perpetually repeating the twaddle, that it is a proof of honourable independence to follow one's own taste without being bound down to the regulation costume of the Philistine cattle, and to choose for clothes the colours, materials and cut which appear beautiful to oneself, no matter how much they may differ from the fashion of the day. The answer to this cackle should be that it is above all a sign of anti-social ego-mania to irritate the majority unnecessarily, only to gratify vanity, or an æsthetical instinct of small importance and easy to control—such as is always done when, either by word or deed, a man places himself in opposition to this majority. He is obliged to repress many manifestations of opinions and desires out of regard for his fellow-creatures; to make him understand this is the aim of education, and he[Pg 14] who has not learnt to impose some restraint upon himself in order not to shock others is called by malicious Philistines, not an Æsthete, but a blackguard.

"It may become a duty to combat the vulgar herd in the cause of truth and knowledge; but to a serious man this duty will always be felt as a painful one. He will never fulfil it with a light heart, and he will examine strictly and cautiously if it be really a high and imperative law which forces him to be disagreeable to the majority of his fellow-creatures. Such an action is, in the eyes of a moral and sane man, a kind of martyrdom for a conviction, to carry out which constitutes a vital necessity; it is a form, and not an easy form, of self-sacrifice, for it means the renunciation of the joy which the consciousness of sympathy with one's fellow-creatures gives, and it exacts the painful overthrow of social instincts, which, in truth, do not exist in deranged ego-maniacs, but are very strong in the normal man.

"The predilection for strange costume is a pathological aberration of a racial instinct. The adornment of the exterior has its origin in the strong desire to be admired by others—primarily by the opposite sex—to be recognised by them as especially well shaped, handsome, youthful, or rich and powerful, or as pre-eminent through rank or merit. It is practised, then, with the[Pg 15] object of producing a favourable impression on others, and is a result of thought about others, of preoccupation with the race. If, now, this adornment be, not through misjudgment but purposely, of a character to cause irritation to others, or lend itself to ridicule—in other words, if it excites disapproval instead of approbation—it then runs exactly counter to the object of the art of dress, and evinces a perversion of the instinct of vanity.

"The pretence of a sense of beauty is the excuse of consciousness for a crank of the conscious. The fool who masquerades in Pall Mall does not see himself, and, therefore, does not enjoy the beautiful appearance which is supposed to be an æsthetic necessity for him. There would be some sense in his conduct if it had for its object an endeavour to cause others to dress in accordance with his taste; for them he sees and they can scandalise him by the ugliness, and charm by the beauty, of their costume. But to take the initiative in a new artistic style in dress brings the innovator not one hair's breadth nearer his assumed goal of æsthetic satisfaction.

"When, therefore, an Oscar Wilde goes about in 'æsthetic costume' among gazing Philistines, exciting either their ridicule or their wrath, it is no indication of independence of character, but rather from a purely anti-socialistic, ego-maniacal recklessness and hysterical longing to make a[Pg 16] sensation, justified by no exalted aim; nor is it from a strong desire of beauty, but from a malevolent mania for contradiction."

It is impossible to read the extracts quoted above—and only a few paragraphs sufficient to show the trend of a much longer article have been used—without realising its injustice and yet at the same time its perfect sincerity. During the "first period," with which we are dealing now, Wilde undoubtedly excited the enmity and ridicule of a vast number of people. He knew that he had something to say which was worth listening to. He knew also—as the genius always has known—that he was superior in intellect to those by whom he was surrounded. His temperament was impatient. He wanted to take the place to which he felt he was entitled in a sudden moment. His quick Celtic imagination ran riot with fact, his immeasurable ambition, his serene consciousness of worth, which to usual minds and temperaments suggested nothing but conceit, all urged him to display and extravagance in order to more speedily mount the rostrum from which he would be heard.

Therefore, in this first period of this so astonishing a career, he went far to spoil and obscure his message by the very means he hoped would enable him to publish it widely. He invented a pose which he intended should become a megaphone, whereas, in the effect, it did but[Pg 17] retard the hearing of his voice until the practical wisdom of what he wished to say proved itself in concrete form.

Nor must we ever forget the man's constant sense of humour, a mocking sprite which doubtless led him to this or that public foolishness while he chuckled within at his own attitude and the dance he was leading his imitators and fools. For Oscar Wilde had a supreme sense of humour. Many people would like to deny him humour, while admitting his marvellous and scintillating wit. That they are wrong I unhesitatingly assert, and I believe that this will be proved over and over again in the following pages.

Let us take another view of Wilde at this period. It was written after his disappearance from public life, or rather when it was imminent and certain. The words are those of Mr Labouchere, the flaneur with an intellect, the somewhat acid critic of how many changing aspects and phases of English social life.

"I have known Oscar Wilde off and on for years," writes Mr Labouchere in Truth. "Clever and witty he unquestionably is, but I have always regarded him as somewhat wrong in the head, for his craving after notoriety seemed to me a positive craze. There was nothing that he would not do to attract attention. When he went over to New York he went about dressed[Pg 18] in a bottle-green coat with a waist up to his shoulders. When he entered a restaurant people threw things at him. When he drove in the evening to deliver his lectures the windows of his carriage were broken, until a policeman rode on each side of it. Far from objecting to all this, it filled him with delighted complacency. 'Insult me, throw mud at me, but only look at me,' seemed to be his creed; and such a creed was never acted upon by anyone whose mind was not out of balance. So strange and wondrous is his mind, when in an abnormal condition, that it would not surprise me if he were deriving a keen enjoyment from a position which most people, whether really innocent or guilty, would prefer to die rather than occupy. He must have known in what a glass house he lived when he challenged investigation in a court of justice. After he had done this he went abroad. Why did he not stay abroad? The possibilities of a prison may not be pleasing to him, but I believe that the notoriety that has overtaken him has such a charm for him that it outweighs everything else. I remember, in the early days of the cult of æstheticism, hearing someone ask him how a man of his undoubted capacity could make such a fool of himself. He gave this explanation. He had written, he said, a book of poems, and he believed in their excellence. In vain he went from publisher to publisher asking[Pg 19] them to bring them out: no one would even read them, for he was unknown. In order to find a publisher he felt that he must do something to become a personality. So he hit upon æstheticism. It succeeded. People talked about him; they invited him to their houses as a sort of lion. He then took his poems to a publisher, who—still without reading them—gladly accepted them."

This is thoroughly unsympathetic, but no doubt it represents a mood with some faithfulness. In criticising the work of critics one must be a psychologist. Religion, the Christian religion at anyrate, teaches tolerance. Its teachings are seldom obeyed. The four Hags of the litany—let us personify them!—Envy, Hatred, Malice, and Uncharitableness unfortunately intrude into religious life too often and too powerfully. But the real psychologist, not the scientist (vide Nordau) is able to understand better than anyone else the motives which have animated criticism at any given date. The psychologist more than any other type of man or woman has learnt the lesson Charles Reade tried to inculcate in "Put Yourself In His Place."

With a little effort, we can realise what Truth thought when these lines were written. We cannot blame the writer, we can only record his words as a part of the general statement[Pg 20] dealing with Oscar Wilde's life and attitude during the "Æsthetic Period."

At this point the reader may possibly ask himself if the title given to the book—"Oscar Wilde: an Appreciation"—is entirely justified. "The writer of it," he may say to himself, "is giving us examples of hostile criticism of Wilde's first period, and though he endeavours to explain them, yet, in an appreciation, it rather seems that such quotations are out of place."

I do not think that if the point of view is considered for a moment, the stricture will be persisted in.

Eulogy, indiscriminating eulogy, is simply an ex parte statement which can have no weight at all. I shall endeavour to show, before this first part of the book is completed, not only how those who attacked Wilde were mistaken, not only how those who bestowed indiscriminate praise upon him made an over-statement, but finally and definitely what Wilde was as seen through the temperament of the writer, corrected by the statements of other writers both for and against him.

I am convinced that this is the only scientific method of arriving at a just estimation of the character of this brilliant and extraordinary man. No summing up of the æsthetic period could be complete without copious references to the great chronicler of our modern life—the pages of Mr[Pg 21] Punch.

Punch has never been bitter. It has often been severe, but Mr Punch has always, from the very first moment of his arrival among us, successfully held the balance between this or that faction, and, moreover, has faithfully reflected the consensus of public opinion upon any given matter.

The extraordinary skill with which some of the brightest and merriest wits have made our national comic paper the true diary of events cannot be controverted or disputed. Follies and fashions have been criticised with satire, but never with spleen. Addison said that the "appearance of a man of genius in the world may always be known by the virulence of dunces." Punch has proved for generations that its kindly appreciation or depreciation has never been virulent, but nearly always an accurate statement of the opinion and point of view of the ordinary more or less cultured and well-bred person.

It has always been a sign of eminence in this or that department of life to be mentioned in Punch at all. The conductors of that journal during its whole career have always exercised the wisest discrimination, and have always kept shrewd fingers upon the pulses of English thought. When a politician, for example, is caricatured in Punch that politician knows that[Pg 22] he has arrived at a certain place and point in public estimation. When a writer is caricatured, either in line or words, he also knows that he has, at anyrate, obtained a hold of this or that sort upon the country.

Now those who would try to minimise the place of Oscar Wilde in the public eye during the æsthetic period have only to look at the pages of Punch to realise how greatly that movement influenced English life during its continuance.

Let it be thoroughly understood—and very few people will attempt to deny it—that Punch has always been a perfectly adjusted barometer of celebrity.

It is, therefore, not out of place, herein, to publish a bibliography of the references to Oscar Wilde which, from first to last of that cometlike career, appeared in the pages of Mr Punch. Such a list proves immediately the one-sidedness of Dr Max Nordau's and Mr Labouchere's views. From extracts I have given from the remarks of these two eminent people the ordinary man might well be inclined to think that the æsthetic movement and the doings of Oscar Wilde in his first period were small and local things. This is not so, and the following carefully compiled list will show that it is not so.

The list has been properly indexed and is now given below. Afterwards I shall give a small[Pg 23] selection from the witticisms of the famous journal to support the bibliography.

Those students of the work of Oscar Wilde and his position in modern life will find the references below of great interest. They date from 1881 to 1906, and those collectors of "Oscariana" and students of Wilde's work will doubtless be able to obtain the numbers in which the following articles, poems, and paragraphs have appeared.

1881

| February | 12, | p. | 62. | Maudle on the Choice of a Profession. |

| " | " | p. | 71. | Beauty Not at Home. |

| April | 9, | p. | 161. | A Maudle in Ballad. To His Lily. |

| " | 30, | p. | 201. | The First of May. An Æsthetic Rondeau. Substitution. |

| May | 7, | p. | 213. | A Padded Cell. |

| " | " | p. | 215. | Design for an Æsthetic Theatrical Poster. "Let Us Live Up To It." |

| " | 14, | p. | 218. | The Grosvenor Gallery. |

| " | " | p. | 220. | Fashionable Nursery Rhyme. |

| " | " | p. | 221. | Philistia Defiant. |

| " | 28, | p. | 242. | More Impressions. By Oscuro Wildegoose. La Fuite des Oies. |

| " | " | p. | 245. | Æsthetic Notes. |

| June | 25, | p. | 297. | Æsthetics at Ascot. |

| " | " | p. | 298. | Punch's Fancy Portraits. No. 37, "O. W." |

| July | 23, | p. | 26. | Swinburne and Water. |

| " | " | p. | 29. | Maunderings at Marlow. (By Our Own Æsthetic Bard.) |

| August | 20, | p. | 84. | "Croquis" by Dumb-Crambo Junior. |

| " | 20, | p. | 84. | Too-Too Awful. A Sonnet of Sorrow. [Pg 24] |

| September | 17, | p. | 132. | Impression De L'Automne. (Stanzas by our muchly-admired Poet, Drawit Milde.) |

| October | 1, | p. | 154. | The Æsthete to the Rose. (By Wildegoose, after Waller.) |

| " | 29, | p. | 204. | Spectrum Analysis. (After "The Burden of Itys," by the Wild-Eyed Poet.) |

| November | 12, | p. | 228. | A Sort of "Sortes." |

| " | 19, | p. | 237. | Poet's Corner; Or, Nonsense Rhymes on Well-known Names. |

| " | 26, | p. | 241. | The Downfall of the Dado. |

| " | " | p. | 242. | Theoretikos. By Oscuro Wildegoose. |

| December | 10, | p. | 274. | "Impressions du Theatre." |

| " | 17, | p. | 288. | The Two Æsthetic Poets. |

| " | 24, | p. | 289. | Mr Punch's "Mother Hubbard" Fairy Tale Grinaway Christmas (Second Series.) |

| " | 31, | p. | 309. | Mrs Langtry as "Lady Macbeth." |

Almanack for 1882 (Dec. 6, 1881) (p. 5). More Impressions. (By Oscuro Wildegoose.) Des Sornettes.

1882

| January | 7, | p. | 10. | "A New Departure." |

| " | " | pp. | 10, 11. | Clowning and Classicism. |

| " | " | p. | 12. | In Earnest. |

| " | 14, | p. | 14. | Oscar Interviewed. |

| " | " | p. | 16. | Æsthetic Ladies' Hair. |

| " | " | p. | 18. | Murder Made Easy. A Ballad à la Mode. By "Brother Jonathan" Wilde. (With Cartoon.) |

| " | " | p. | 18. | To An Æsthetic Poet. |

| " | " | p. | 22. | Impression du Theatre. |

| February | 4, | p. | 49. | Sketches from "Boz." Oscar Wilde as Harold Skimpole. |

| " | 4, | p. | 58. | A Poet's Day. Ariadne in Naxes;[Pg 25] Or, Very Like a Wail. |

| " | " | p. | 49. | Distinctly Precious Pantomime. |

| " | 18, | p. | 81. | Lines by Mrs Cimabue Brown. |

| March | 11, | p. | 109. | The Poet Wilde's Unkissed Kisses. |

| " | " | p. | 117. | Ossian (with Variations). |

| April | 1, | p. | 153. | A Philistine to An Æsthete. |

| " | " | p. | 156. | The Poet Wilde. |

| " | 8, | p. | 168. | Impression De Gaiety Théâtre. By Ossian Wilderness. |

| " | 22, | p. | 192. | Likely. |

| November | 4, | p. | 216. | Not Generally Known. |

| " | 25, | p. | 249. | "What! No Soap!" Or, Pop Goes The Langtry Bubble. |

1883

| March | 31, | p. | 155. | To Be Sold. |

| " | " | p. | 156. | Sage Green. (By a Fading-out Æsthete.) |

| May | 12, | pp. | 220-1. | Our Academy Guide. No. 163.—Private Frith's View.— Members of the Salvation Army, led by General Oscar Wilde, joining in a hymn. |

| September | 1, | p. | 99. | "The Play's (not) the Thing." |

| November | 3, | p. | 209. | Sartorial Sweetness and Light. |

| " | 10, | p. | 218. | Counter Criticism. |

| " | 17, | p. | 231. | Cheap Telegrams. |

| " | " | p. | 238. | Another Invitation to Amerikay. |

| " | 24, | p. | 249. | "And is this Fame?" |

1884

| June | 14, | p. | 288. | The Town. II.—Bond Street. |

| August | 23, | p. | 96. | The Town. No. XI.—"Form." A Legend of Modern London. Part I. |

| " | 30, | p. | 105. | A Legend of Modern London. Part II. |

1885[Pg 26]

| May | 30, | p. | 253. | Ben Trovato. |

| June | 27, | p. | 310. | Interiors and Exteriors. No. 13. At Burlington House. The "Swarry." |

| December | 7, | Almanack for 1886. The Walnut Season. "Here Y' ar'. Ten a Penny. All Cracked." |

1887

| December | 10, | p. | 276. | Our Booking-Office. Woman's World. |

1889

| January | 5, | p. | 12. | Our Booking-Office. Article in The Fortnightly. |

| July | 6, | p. | 12. | Advertisement of Blackwood's Magazine, containing "The Portrait of Mr W. H." by Oscar Wilde. |

| October | 5, | p. | 160. | Appropriate Subject. |

1890

| July | 19, | p. | 26. | Our Booking-Office. Dorian Gray. |

| September | 20, | p. | 135. | Development. |

| Christmas Number. | Punch Among the Planets. |

1891

| March | 14, | p. | 123. | Desdemona to the Author of "Dorian Gray." (Apropos of his paragraphic Preface.) |

| " | " | p. | 125. | Wilde Flowers. |

| May | 30, | p. | 257. | Our Booking-Office. Intentions. |

1892

| March | 5, | p. | 113. | A Wilde "Tag" to a Tame Play. With Fancy Portrait. "Quite Too-Too Puffickly Precious." |

| March | 12, | p. | 123. | Lord Wildermere's Mother-in-Law. [Pg 27] |

| " | " | p. | 124. | Pathetic Description of the Present State of Mr George Alexander. |

| April | 30, | p. | 215. | Staircase Scenes.—No. 1, Private View, Royal Academy. |

| June | 25, | p. | 304. | The Playful Sally. |

| July | 2, | p. | 315. | A Difficulty. |

| " | 9, | p. | 1. | A Wilde Idea; Or, More Injustice to Ireland. |

| " | 16, | p. | 16. | On the Fly-leaf of an Old Book. |

| " | 16, | p. | 23. | Racine, With the Chill Off. |

1893

| January | 19, | p. | 29. | "To Rome for Sixteen Guineas." |

| April | 22, | p. | 189. | The B. and S. Drama at the Adelphi. |

| " | 29, | p. | 193. | Stray Thoughts on Play-Writing. |

| " | " | p. | 195. | The Premier at the Haymarket last Wednesday. |

| May | 6, | p. | 213. | A Work—of Some Importance. |

| " | 13, | p. | 221. | Wilder Ideas; Or, Conversation as she is spoken at the Haymarket. |

| " | 27, | p. | 246. | A Wylde Vade Mecum. (By Professor H-xl-y) |

| June | 3, | p. | 257. | Second Title for the Play at the Haymarket. |

| July | 15, | p. | 13. | An Afternoon Party. |

| " | 15, | p. | 22. | "The Play is Not the Thing." |

| " | 29, | p. | 46. | At The T. R. H. |

| August | 26, | p. | 94. | Still Wilder Ideas. (Possibilities for the next O. Wilde Play.) |

| December | 30, | pp. | 304-5. | New Year's Eve at Latterday Hall. An Incident. Dorian Gray taking Juliet in to Dinner. |

1894[Pg 28]

| February | 17, | p. | 73. | "Blushing Honours." |

| March | 10, | p. | 109. | She-Notes. By Borgia Smudgiton. |

| July | 21, | p. | 33. | The Minx.—A Poem in Prose. |

| August | 4, | p. | 60. | Our Charity Fete. |

| October | 13, | p. | 177. | The O.B.C. (Limited). |

| " | 20, | p. | 185. | The Blue Gardenia. (A Colourable Imitation.) |

| " | 27, | p. | 204. | Morbidezza. |

| November | 10, | p. | 225. | The Decadent Guys. (A Colour-Study in Green Carnations.) |

| December | 15, | p. | 287. | The Truisms of Life. (Note 12.) |

1895

| January | 12, | p. | 24. | Overheard Fragment of a Dialogue. |

| " | 19, | p. | 29. | "To Rome for Sixteen Guineas." |

| " | " | p. | 36. | "A penny Plain—But Oscar Coloured." |

| February | 2, | p. | 54. | A Wilde "Ideal Husband." |

| " | " | p. | 60. | A God in the Os-Car. |

| " | 23, | p. | 85. | The O. W. Vade Mecum. |

| March | 2, | p. | 106. | "The Rivals" at the A.D.C. |

| " | " | p. | 107. | The Advisability of Not Being Born in a Handbag. |

| " | 16, | p. | 121. | The Advantage of Being Consistent. |

| April | 6, | p. | 157. | April Foolosophy. (By One of Them.) |

| " | 13, | p. | 171. | The Long and Short of It. |

| " | " | p. | 177. | Concerning a Misused Term; viz. Art, as recently applied to a certain form of Literature. |

1906

| January | 3, | p. | 18. | Our Booking-Office. (R. H. Sherard's "Twenty Years in Paris.") |

This list at least spells, and spelt, celebrity and[Pg 29] a recognition of the importance of the Æsthetic movement.

Especially did the American lecturing tour of Oscar Wilde excite the comment and ridicule of Punch.

I quote some paragraphs from a pretended despatch from an "American correspondent."

A POET'S DAY

(From an American Correspondent)

Oscar at Breakfast! Oscar at Luncheon!! Oscar at Dinner!!! Oscar at Supper!!!! "You see I am, after all, but mortal," remarked the Poet, with an ineffable affable smile, as he looked up from an elegant but substantial dish of ham and eggs. Passing a long, willowy hand through his waving hair, he swept away a stray curl-paper with the nonchalance of a D'orsay.

After this effort, Mr Wilde expressed himself as feeling somewhat faint; and, with a half-apologetic smile, ordered another portion of

HAM AND EGGS

in the evident enjoyment of which, after a brief interchange of international courtesies, I left the Poet.

The irresponsible but not ungenial and quite legitimate fun of this is a fairly representative[Pg 30] indication of the way in which the young "Apostle of Beauty" was thought of in England during his American visit.

The writer goes on to tell how, later in the day, he once more encountered the "young patron of Culture." It is astonishing to us now to realise how even the word "culture" was distorted from its real meaning and made into the badge of a certain set. At anyrate, Mr Punch's contributor goes on to say that "Oscar" was found at the business premises of the

CO-OPERATIVE DRESS ASSOCIATION.

On this occasion the Poet, by special request, appeared in the uniform of an English Officer of the Dragoon Guards, the dress, I understand, being supplied for the occasion from the elegant wardrobe of Mr D'oyley Carte's "Patience" Company.

Several ladies expressed their disappointment at the "insufficient leanness" of the Poet's figure, whereupon his Business Manager explained that he belonged to the fleshy school.

To accommodate Mr Wilde, the ordinary lay-figures were removed from the showroom, and, after a sumptuous luncheon, to which the élite of Miss ——'s customers were invited, the distinguished guest posed with his fair hostess in an allegorical tableau, representing English Poetry extending the right hand to American Commerce.[Pg 31]

"This is indeed Fair Trade," remarked Mr Wilde lightly, and immediately improvised a testimonial advertisement (in verse) in praise of Miss ——'s patent dress-improver.

At a dinner given by "Jemmy" Crowder (as we familiarly call him), the Apologist of Art had discarded his military garb for the ordinary dress of an

ENGLISH GENTLEMAN

in which his now world-famed knee-breeches form a conspicuous item, suggesting indeed the Admiral's uniform in Mr D'Oyley Carte's "Pinafore" combination.

"I think," said the Poet, in a pause between courses, "one cannot dine too well"—placing everyone at his ease by his admirable tact in partaking of the thirty-six items of the menu.

The skit continues wittily enough, but it is not necessary to quote more of it. The paragraphs sufficiently explain the attitude of Mr Punch, which was the general attitude at the time.

It was hammered in persistently. "Oscar Interviewed" appeared under the date of January 1882, and again, in the following extracts the reader will recognise the same note.

"Determined to anticipate the rabble of[Pg 32] penny-a-liners ready to pounce upon any distinguished foreigner who approaches our shores, and eager to assist a sensitive Poet in avoiding the impertinent curiosity and ill-bred insolence of the Professional Reporter, I took the fastest pilot-boat on the station, and boarded the splendid Cunard steamer, the Boshnia, in the shucking of a peanut."

HIS ÆSTHETIC APPEARANCE

He stood, with his large hand passed through his long hair, against a high chimney-piece—which had been painted pea-green, with panels of peacock-blue pottery let in at uneven intervals—one elbow on the high ledge, the other hand on his hip. He was dressed in a long, snuff-coloured, single-breasted coat, which reached to his heels, and was relieved with a sealskin collar and cuffs rather the worse for wear. Frayed linen, and an orange silk handkerchief, gave a note to the generally artistic colouring of the ensemble, while one small daisy drooped despondently in his buttonhole.... We may state that the chimney-piece, as well as the sealskin collar, is the property of Oscar, and will appear in his Lectures "on the Growth of Artistic Taste in England."

HE SPEAKS FOR HIMSELF

"Yes; I should have been astonished had I not been interviewed! Indeed, I have not been well[Pg 33] on board this Cunard Argosy. I have wrestled with the glaukous-haired Poseidon, and feared his ravishment. Quite: I have been too ill, too utterly ill. Exactly—seasick in fact, if I must descend to so trivial an expression. I fear the clean beauty of my strong limbs is somewhat waned. I am scarcely myself—my nerves are thrilling like throbbing violins—in exquisite pulsation.

"You are right. I believe I was the first to devote my subtle brain-chords to the worship of the Sunflower, and the apotheosis of the delicate Tea-pot. I have ever been jasmine-cradled from my youth. Eons ago, I might say centuries, in '78, when a student at Oxford, I had trampled the vintage of my babyhood, and trod the thorn-spread heights of Poesy. I had stood in the Arena and torn the bays from the expiring athletes, my competitors."

LECTURE PROSPECTS

"Yes; I expect my Lecture will be a success. So does Dollar Carte—I mean D'Oyley Carte. Too-Toothless Senility may jeer, and poor, positive Propriety may shake her rusty curls; but I am here in my creamy lustihood, to pipe of Passion's venturous Poesy, and reap the scorching harvest of Self-Love! I am not quite sure what I mean. The true Poet never is. In fact,[Pg 34] true Poetry is nothing if it is intelligible. She is only to be compared to Salmacis, who is not a boy or girl, but yet is both."

And so forth, and so forth.

About the conversation and superficial manner of Oscar Wilde there must have been something strangely according to formula. Among intimate friends, friends who were sympathetic to his real ideals, his talk was wonderful. That fact is vouched for in a hundred quarters, it is not to be denied.

As I write I have dozens of undeniable testimonies to the fact, I myself can bear witness to it on at least one occasion. But when Wilde was not with people for whose opinion of him he cared much—really cared—his odd perversity of phrase, his persistent wish to astonish the fools, his extraordinary carelessness of average opinion often compelled him to talk the most frantic nonsense which was only redeemed from mere childish inversion of phrase by the air and manner with which it was said, and the merest tinsel pretence of wit. The wittiest talker of his generation, certainly the wittiest writer, gave the very worst of his wit to the pressmen who pestered him but who, and this was the thing he was unable to appreciate at its true value, represented him to the world during this "first period."

The mock interviews in Punch which have[Pg 35] been quoted from are really no very wide departures from the real thing. A year or two after the Æsthetic movement was not so prominent in the public eye as was the success of Wilde as a writer of plays, an actual interview with him appeared in a well-known weekly paper in which he talked not much less extravagantly than he was caricatured as talking in Punch. A play of his had been produced and, while it was a complete and satisfying success, it had been assailed in that unfortunately hostile way by the critics to which he was accustomed.

He was asked what he thought about the attitude of the critics towards his play.

"For a man to be a dramatic critic," he is said to have replied, "is as foolish and inartistic as it would be for a man to be a critic of epics, or a pastoral critic, or a critic of lyrics. All modes of art are one, and the modes of the art that employs words as its medium are quite indivisible. The result of the vulgar specialisation of criticism is an elaborate scientific knowledge of the stage—almost as elaborate as that of the stage-carpenter, and quite on a par with that of the call-boy—combined with an entire incapacity to realise that a play is a work of art, or to receive any artistic impressions at all."

He was told that he was rather severe upon the dramatic critics.

"English dramatic criticism of our own day[Pg 36] has never had a single success, in spite of the fact that it goes to all the first nights," was his reply.

Thereupon the interviewer suggested that dramatic criticism was at least influential.

"Certainly; that is why it is so bad," he replied, and went on to say:

"The moment criticism exercises any influence it ceases to be criticism. The aim of the true critic is to try and chronicle his own moods, not to try and correct the masterpieces of others."

"Real critics would be charming in your eyes, then?"

"Real critics? Ah, how perfectly charming they would be! I am always waiting for their arrival. An inaudible school would be nice. Why do you not found it?"

Oscar Wilde was asked if there were, then, absolutely no critics in London.

"There are just two," he answered, but refused to give their names. The interviewer goes on to recount his exact words:

"Mr Wilde, with the elaborate courtesy for which he has always been famous, replied, 'I think I had better not mention their names; it might make the others so jealous.'

"'What do the literary cliques think of your plays?'

"'I don't write to please cliques; I write to please myself. Besides, I have always had grave[Pg 37] suspicions that the basis of all literary cliques is a morbid love of meat-teas. That makes them sadly uncivilised.'

"'Still, if your critics offend you, why don't you reply to them?'

"'I have far too much time. But I think some day I will give a general answer, in the form of a lecture, in a public hall, which I shall call "Straight Talks to Old Men."'

"'What is your feeling towards your audiences—towards the public?'

"'Which public? There are as many publics as there are personalities.'

"'Are you nervous on the night that you are producing a new play?'

"'Oh no, I am exquisitely indifferent. My nervousness ends at the last dress rehearsal; I know then what effect my play, as presented upon the stage, has produced upon me. My interest in the play ends there, and I feel curiously envious of the public—they have such wonderful fresh emotions in store for them.'

"I laughed, but Mr Wilde rebuked me with a look of surprise.

"'It is the public, not the play, that I desire to make a success,' he said.

"'But I'm afraid I don't quite understand——'

"'The public makes a success when it realises[Pg 38] that a play is a work of art. On the three first nights I have had in London the public has been most successful, and had the dimensions of the stage admitted of it, I would have called them before the curtain. Most managers, I believe, call them behind.'"

There are pages more of this sort of thing, and the earlier and pretended interview in Punch differs a little in period but very little in manner from this real interview.

Punch continued its gibes during the whole time of the first period. Really witty parodies of Oscar Wilde's poems and plays appeared from time to time. Pictures of him were drawn in caricature by well-known artists. It was the same in almost every society. The band of enthusiasts listened to the message, but gave more prominence to the poses and extravagances which accompanied it. The message was obscured and it was the fault of Oscar Wilde's eccentricity.

We are reaping the benefit of it all now, at present I am merely the chronicler of opinion when the movement was in what the unobservant thought was its heyday, but which has proved to be its infancy.

The chorus of dislike and mistrust was almost universal. At Oxford itself, popularly supposed to be a stronghold of æstheticism at the time, a debate on the question took place at the Union.[Pg 39] A very prominent undergraduate of the day, Mr J. A. Simon, of Wadham College, reflected the bulk of Oxford opinion when he spoke as follows:—

"Mr J. A. Simon (Wadham) said he felt nervous, for it was an extraordinary occasion for him to be on the side that would gain a majority. He did not consider that the motion had at all the meaning the mover gave it. He quite agreed with him as to the advances made in the illustrated press, and other things, and that many of these selected changes were good. The motion, however, evidently referred to the movement headed by Oscar Wilde, and represented by such things as the 'Yellow Book,' etc. He always thought that the mover was most natural when he was on the stage (applause) and they had all been given pleasure by his impersonations (applause). He believed, though, that he had been acting that night, and the speaker quoted from the speeches of Bassanio passages which he considered described the way the mover had led them off the scent. He intended to discuss the matter seriously. As a book entitled 'Degeneracy' pointed out, the new movement was the outcome of a craving for novelty, and the absurdities in connection with it would do credit to a madhouse. People were eccentric in the hope that they would be taken to be original (applause). It was not a[Pg 40] development at all; it was but a jerk or twitching, the work of a moment. Oscar Wilde had actually signed his name to a most awful pun, as those who had seen 'The Importance Of Being Earnest' would understand. The writer's many epigrams were doubtless clever, for next to pretending to be drunk, pretending to be mad was the most difficult (applause). The process was to turn a proverb upside down, and there was the epigram. Then Aubrey Beardsley's figures, if they showed anything, showed extraordinary development; they certainly were not delicate; in fact, he should call them distinctly indelicate. For one thing, such creatures never existed, and it was a species of art that was absolutely imbecile. Oscar Wilde, though, had said that until we see things as they are not we never really live. But all he could say was that he hoped he should never live (applause). It was really not art at all, for art was nearly allied to nature, although Oscar Wilde said that the only connecting link was a really well-made buttonhole. That sort of thing was the art of being brilliantly absurd (applause). It was insignificant to lay claim to manners on the ground of personal appearance; such were not manners but mannerisms. Aubrey Beardsley's figures were but a mannerism of this sort (applause). A development must be new and permanent, and the pictures referred[Pg 41] to were not new, for similar ones could be found on the old Egyptian monuments (applause). This cult were not even original individually, for where one led all the rest followed. Oscar Wilde talked about a purple sin: the others did the same. By-the-by, that remark was not original, for scarlet sins had been mentioned in very early days; it was indeed all of it but a resuscitation of what was old and had been long left behind by the rest of the world (applause). The movement was not permanent, as might be seen by the æsthetic craze of fifteen years ago. Velvet coats and peacock feathers were dying out, and soon it would not be correct to wear the hair long (laughter). It was but a phase; if everyone were to talk in epigrams it would be distinguished to talk sense. He was in a difficulty, for if he got a large majority against the motion, to be in a minority was just what would please the æsthetes most. Therefore, let as few vote against as possible (laughter). To be serious, he considered that true art should give pleasure and comfort to people who were in trouble or down in the world, and who, he asked, would be helped by the art of either Aubrey Beardsley or Oscar Wilde? (applause). In conclusion, he would ask the House to give the movers the satisfaction of having as few as possible voting for them (applause)."

said a popular rhyme of the time. It sums up average opinion and may fittingly close this summary of it during the "Æsthetic" period.

We are forced to admit that the general misunderstanding was partially due to the fashion in which the new doctrines were presented. The thing was well worth saying, but it was not said seriously enough. It was a lamentable mistake, but it helps us to understand a certain aspect of Oscar Wilde: the man.

At the time in which what I have called the "second period" may be said to have begun, Wilde was emerging from the somewhat obscuring influences of the Æsthetic movement and was in a state of transition.

He was then editing a magazine known as The Woman's World, and doing his work with a conscientiousness and sense of responsibility which shows us another side of him and one which, to the sane, if limited, English temperament is a singularly pleasant one. He had moaned, money must be earned, and he earned[Pg 43] it faithfully under a discipline. It is a speculation not without interest when we wonder to what heights such a man might not have risen if a discipline such as this had been more continuous.

"Lord of himself, that heritage of woe," sang Lord Byron, well aware from personal experience of the constant dangers, the almost certain shipwreck that the life of perfect freedom has for such as he was, and for such a temperament as Wilde's also.

Oscar was living in a beautiful house at Chelsea, and it is a remarkable instance of how surely the first period had merged into the second when we find that the decorations of his home were beautiful indeed, but not much like those he had preached about and insisted on in his æsthetic lectures and writings.

There was an utter lack of so-called æsthetic colouring in the house where Mr and Mrs Wilde had made their home. The scheme consisted, indeed, of faded and delicate brocades, against a background of white or cream painting, and was French rather than English.

Rare engravings and etchings formed a deep frieze along two sides of the drawing-room, and stood out on a dull-gold background, while the only touches of bright colour in the apartment were lent by two splendid Japanese feathers let into the ceiling, while, above the white, carved mantelpiece, a gilt-copper bas-relief, by Donaghue,[Pg 44] made living Oscar Wilde's fine verses, "Requiescat."

Not the least interesting work of art in this characteristic sitting-room was a quaint harmony in greys and browns, purporting to be a portrait of the master of the house as a youth; a painting which was a wedding present from Mr Harper Pennington, the American artist.

The house could boast of an exceptionally choice gallery of contemporary art. Close to a number of studies of Venice, presented by Mr Whistler himself, hung an exquisite pen-and-ink illustration by Walter Crane. An etching of Bastien Le Page's portrait of Sarah Bernhardt contained in the margin a few kindly words written in English by the great tragedienne.

Mrs Oscar Wilde herself had strong ideas upon house decoration. She once told an inquirer that "no one who has not tried them knows the value of uniform tints and a quiet scheme of colouring. One of the most effective effects in house decoration can be obtained by having, say, the sitting-room pure cream or white, with, perhaps, a dado of six or seven feet from the ground. In an apartment of this kind, ample colouring and variety will be introduced by the furniture, engravings, and carpet; in fact, but for the trouble of keeping white walls in London clean, I do not think there can be anything prettier and more practical than this mode of[Pg 45] decoration, for it is both uncommon and easy to carry out. I am not one of those," continued Mrs Wilde, "who believe that beauty can only be achieved at considerable cost. A cottage parlour may be, and often is, more beautiful, with its unconsciously achieved harmonies and soft colouring, than a great reception-room, arranged more with a view to producing a magnificent effect. But I repeat, of late, people, in their wish to decorate their homes, have blended various periods, colourings and designs, each perhaps beautiful in itself, but producing an unfortunate effect when placed in juxtaposition. I object also to historic schemes of decoration, which nearly always make one think of the upholsterer, and not of the owner of the house."

In conjunction with her husband, Mrs Wilde had also thought out the right place of flowers in the decoration of a house. She would say: "It is impossible to have too many flowers in a room, and I think that scattering cut blossoms on a tablecloth is both a foolish and a cruel custom, for long before dinner is over the poor things begin to look painfully parched and thirsty for want of water. A few delicate flowers in plain glass vases produce a prettier effect than a great number of nosegays, and yet, even though people may see that something is wrong, many do not realise how easily a[Pg 46] charming effect might be produced with the same materials somewhat differently disposed.

"A Japanese native room, for example, is furnished with dainty simplicity, and one flower and one pot supply the Jap's æsthetic longing for decoration. When he gets tired of his flower and his pot, he puts them away, and seeks for some other scheme of colour produced by equally simple means."

Oscar Wilde now began to take a definite place in the English social world. His wit, his brilliance of conversation, his singular charm of manner all combined to render him a welcome guest, and in many cases a valued friend, in circles where distinction of intellect and charm of personality are the only passports. He began to make money and to indulge a natural taste for profusion and splendour. Yet, let it be said here, and said with emphasis, that greatly as he desired, and acquired, the elegances of life, increasing fortune found him as kind and generous as before. It is a known fact that he gave away large sums of money to those less fortunate in the effort to make an income by artistic pursuits. His purse was always open to the struggling and the unhappy and his influence constantly exerted on their behalf.

Suddenly all London was captured by the brilliant modern comedies he began to write. Success of the completest kind had arrived, the[Pg 47] poet's name was in everyone's mouth. Curiously enough it is the French students of Wilde's career who have paid the most attention to Wilde in this second period. The man of society, the witty talker, the maker of epigrams—Wilde at his apogee just before his fall—this is the picture on which the Latin psychologists have liked to dwell.

"In our days, the master of repartee and the after-dinner speaker is foredoomed to forgetfulness, for he always stands alone, and to gain applause has to talk down to and flatter lower-class audiences. No writer of blood-curdling melodramas, no weaver of newspaper novels is obliged to lower his talent so much as the professional wit. If the genius of Mallarmé was obscured by the flatterers that surrounded him, how much more was Wilde's talent overclouded by the would-be-witty, shoddy-elegant, and cheaply-poetical society hangers-on, who covered him with incense. We are told that the first attempts of the sparkling talker were by no means successful in the Parisian salons.

"In the house of Victor Hugo, seeing he must wait to let the veteran sleep out his nap whilst others among the guests slumbered also, he made up his mind to astonish them. He succeeded, but at what a cost! Although he was a verse writer, most sincerely devoted to poetry and art, and one of the most emotional and sensitive and[Pg 48] tender-hearted amongst modern wielders of the pen, he succeeded in gaining only a reputation for artificiality.

"We all know his studied paradoxes, his five or six continually repeated tales, but we are tempted to forget the charming dreamer who was full of tenderness for everything in nature."

Thus M. Charles Grolleau, and there is much in his point of view. The writer of "The Happy Prince" and "The House of Pomegranates" is a different person from the paradoxical causeur who went cometlike through a few London and Paris seasons before disappearing into the darkness of space.

And it was the encouragement and applause bestowed upon Oscar Wilde during the second period that not only confirmed him in his determination to live as the complete flaneur, but which prevented even sympathetic critics from appreciating his work at its true worth.

The late M. Hugues Rebell, who knew him fairly intimately, said of him:

"It is true that Mallarmé has not written much, but all he has done is valuable. Some of his verses are most beautiful, whilst Wilde seemed never to finish anything. The works of the English æsthete are very interesting, because they characterise his epoch; his pages are useful from a documentary point of view, but are not extraordinary from a literary standpoint.[Pg 49] In the 'Duchess of Padua,' he imitates Hugo and Sardou; the 'Picture of Dorian Gray' was inspired by Huysmans; 'Intentions' is a vade mecum of symbolism, and all the ideas contained therein are to be found in Mallarmé and Villiers de l'Isle-Adam. As for Wilde's poetry, it closely follows the lines laid down by Swinburne. His most original composition is 'Poems in Prose.' They give a correct idea of his home-chat, but not when he was at his best; that, no doubt, is because the art of talking must always be inferior to any form of literary composition. Thoughts properly set forth in print after due correction must always be more charming than a finely sketched idea hurriedly enunciated when conversing with a few disciples. In ordinary table-talk we meet nothing more than ghosts of new-born ideas foredoomed to perish. The jokes of a wit seldom survive the speaker. When we quote the epigrams of Wilde, it is as if we were exhibiting in a glass case a collection of beautiful butterflies, whose wings have lost the brilliancy of their once gaudy colours. Lively talk pleases, because of the man who utters it, and we are impressed also by the gestures which accompany his frothy discourse. What remains of the sprightly quips and anecdotes of such celebrated hommes d'esprit as Scholl, Becque, Barbey d'Aurevilly! Some stories of the eighteenth century have been transmitted[Pg 50] to us by Chamfort, but only because he carefully remodelled them by the aid of his clever pen."

Yet during all the time of his success, when he was receiving flattery enough, celebrity enough, money enough to turn the head of a far stronger-willed man than he was, there is abundant evidence of a frequent aspiration after better things. Serene and lofty moods came to him now and again and found utterance in his words or writings.

From the very beginning of his career he had been in the public eye. Now he had, it seemed, come into his own. The years of ridicule and misrepresentation, the years of the first period, were over and done with. A real and solid popularity seemed to be his. Yet, just as he had spoilt and obscured his æsthetic message by those eccentricities which the Anglo-Saxon mind will not permit in anyone who comes professing to teach it, so now Oscar Wilde was to spoil the triumphs of the second period by a mental intoxication that led him step by step to ultimate ruin and disgrace.

At this moment let us sum up the results at which we have arrived in the study of this complex character. We are all of us complex, but Wilde was more strangely compounded than the ordinary man in exact proportion as his intelligence was greater and his power beyond[Pg 51] the general measure. This much and no more.

We have seen that the great fault of Wilde's career up to this period was that of an unconquerable egoism. He was complex only because such mighty gifts as those with which he was dowered were united to a temperament naturally gracious, kindly, and that of a gentleman in the best sense of the word, while both were obscured by a self-appreciation and confidence which reached not only the heights of absurdity but surely impinged upon the borders of mental failure. As he himself said over and over again after his downfall, he had nobody but himself to blame for it. Generous-hearted, free with all material things, kind to the unfortunate, gentle to the weak—Oscar Wilde was all these things. Yet, at the same time, he committed the most dreadful crimes against the social well-being; without a thought of those his influence led into terrible paths, without a thought of those nearest and dearest to him, he deliberately imposed upon them a horror and a shame with an extraordinary and almost unparalleled callousness and hardness of heart.

Bound up in the one man were the twin natures of an angel of light and an angel of dark. It is the same with all men, but never perhaps in the history of the world, certainly never in the history of literature, is there to be found a contrast so astonishing. It is not for the writer[Pg 52] of this study to hold the balance and to say which part of his nature predominated. Opinion about him is still divided into two camps, and this book is a statement from which everyone can draw his own conclusion, and does not attempt to do more than provide the materials for doing so. Yet, the explanation of it all, if explanation there is, seems simple enough. There was an extraordinary and abnormal divorce between will-power and intelligence. Heavy indulgence grew and grew and gradually obscured the finer nature until he imagined his will was supreme and his wishes the only law. The royal intellect dominated the soul and grew by what it fed on, until it unseated the reason, and Wilde fell never to rise again, except only in his work.

At the end of the second period came the frightful exposure and scandals which sent the author into prison. It is no part of this book to touch upon these scandals or to do more than breathe the kindly hope that Wilde was unconscious of what he did, and was totally incapable of realising its enormity.

The third period, in this attempt at chronicling the various phases of his life and temperament, might be said to have begun on the day of his arrest, when his long agony and punishment were to begin. Greatly as he deserved a heavy punishment, not so much as for what he[Pg 53] did to himself but because of the corrupting influence his life and association with others had upon a large section of society, it is yet a moot point whether he did not suffer for others and was made their scapegoat. The true history of this terrible period cannot be written and never will be written. Yet, those who know it in its entirety will say that Wilde bore the penalty for the transgressions of many other people in addition to the just punishment he received for his own.

Few nobler things can be said of any man than this. Let it be eternally placed to his credit that he made no endeavour to lighten his own punishment by implicating others. In more than one instance the betrayal of a friend would undoubtedly have lessened the cumulative burden of the indictment brought against him. He betrayed none of his friends.

This beautiful thread of brightness in the dark warp and woof of Wilde's life at this moment must not be forgotten by those who would estimate his character. It is one of the few relieving lights in the blackness with which the third period opens. And yet, there is still something that can be said for Wilde at this[Pg 54] time which certainly provides the student with another aspect of him. It is the way in which he met his fate and was prepared to endure his punishment, although it would have been simple for him to have avoided it. To avoid the consequences of what he had done, inasmuch as the ruin of his career is concerned, was, of course, impossible. That, indeed, was to be the heaviest part of his penalty. Yet, had he so chosen, imprisonment and the frightful agony of the two years need never have been his portion. A French critic writing of him in the Mercure de France takes an analytical view of this fact, which I do not think is the true one, though, nevertheless, it is interesting. He says: "Neither his own heedlessness nor the envious and hypocritical anger of his enemies, nor the snobbish cruelty of social reprobation were the true cause of his misfortunes. It was he himself who, after a time of horrible anguish, consented to his punishment, with a sort of supercilious disdain for the weakness of human will, and out of a certain regard and unhealthy curiosity for the sportfulness of fate. Here was a voluptuary seeking for torture and desiring pain after having wallowed in every sensual pleasure. Can such conduct have been due to aught else but sheer madness?"

That is all very well, but it does not bear the stamp of truth. It is an interesting point of[Pg 55] view and nothing more. The conduct of Wilde when he at last came athwart the horror of his destiny, when he realised what all the world realised, that he must answer for his sins before the public justice of England, was not unheroic, nor without a fine and splendid dignity. At this time I would much prefer to say, and all the experiences of those around him confirm it, that Wilde knew that it was his duty to himself to endure what society was about to mete out to him. To say that he was a mere gloomy and jaded voluptuary who wished to taste the pleasures of the most horrible and sordid pain, is surely to talk something perilously like nonsense, though full of one of those minute psychological presumptions so dear to a certain type of Latin mind.

Let it be remembered that Oscar Wilde refused to betray his friends, and in the light of that fact, let us see whether his motive for remaining in England to "face the music," as his brother, William Wilde, expressed it, was not something high and worthy in the midst of this hideous wreck and bankruptcy of his fortune. A friend who was with him then, his biographer, and a man of position in English letters, said that when the subject of flight was discussed, he declared to Wilde that, in his opinion, it was the best thing he could do, not only in his own interests but in those of the public too. This[Pg 56] self-sacrificing friend offered to take all the responsibility of the flight upon his own shoulders and to make all the arrangements for it being carried out.

It must be remembered that, at the time Wilde was out on bail, and it has since been proved, with as much certainty as anything of the sort can be proved, that he was not watched by the police, and that even between the periods of his first and second trials, if he had secretly left the country and sought a safe asylum on the Continent, everybody would have felt relieved and the public would have been spared a repetition of the horrors which had already filled the pages of the newspapers to repletion. After the collapse of the action Oscar Wilde brought against Lord Queensberry, he was allowed several hours before the warrant for his arrest was executed in order that he might leave the country. "But imitative of great men in their whims and fancies, he refused to imitate the base in acts which he deemed cowardly. I do not think he ever seriously considered the question of leaving the country, and this, in spite of the fact that the gentleman who was responsible for almost the whole of the bail, had said, 'it will practically ruin me if I lose all that money at the present moment, but if there is a chance, even after conviction, in God's name let him go.'"

Whatever Wilde's motive was for staying to[Pg 57] "face the music," we cannot deny that it was fine. Either he felt that he must endure the punishment society was to give him because he had outraged the law of society, or else he was unwilling to ruin the disinterested and noble-minded man—a gentleman who had only the slightest acquaintance with him—who had furnished the amount of his bail.

Let these facts be written to his credit and considered when the readers of this memoir pass their judgment upon his character.

At the beginning of this third period public opinion which, but a short time ago, had simply meant a chorus of public adulation, except for a minority of people who either envied his successes or honestly reprobated his attitude towards art and life, was now terribly bitter, venomous, and full of spleen and hatred.

Society, however much society was disposed to deny the fact, had set up an idol in their midst. It was partly owing to the senseless and indiscriminate adulation of its idol that its foundations were undermined and that it fell with so resonant a crash. When it was down society assailed it with every ingenuity of reprobation and hatred that it knew how to voice and use.

Nothing was too bad to be said about the erstwhile favourite who, let it be remembered, was not yet adjudged guilty but who, if ever a man was, was denied the application of the prime[Pg 58] principle of English criminal law, which says that every man accused is to be deemed innocent until guilt has been proved against him. People gloated over the downfall.

When Wilde was first arrested and placed in Holloway, and before he was admitted to bail, the more scurrilous portion of the press was full of sickening pictures, both in line and words, of the fallen creature's agony.

Contrasts were drawn by little pens dipped in venom, and the writer of this memoir has in his possession a curious and saddening collection of the screeds of those days, a collection which shows how innate the principle of cruelty is still in the human mind despite centuries of civilisation and the influence of the Cross, which forbids gladiators to slay each other in the arena but allows a more subtle and terrible form of savage sport than anything that Nero or Caligula ever saw or promulgated.

It is unnecessary to quote largely from the productions which disgraced the English press at this time. One single article will serve to prove the point. Let those who read it learn tolerance from this mock sympathy and cruel dwelling upon the tortures of one so recently high in public popularity and esteem, still presumably innocent by English law, and yet placed under the vulgar microscope of the morbid-minded and the lovers of sensation at[Pg 59] any cost.

"Figuratively speaking but yesterday Oscar Wilde was the man of the hour, and to him, and him alone, we looked for our wit, our epigrams, and our learned and interesting plays. But what a change! To-day, Oscar Wilde, the wit, the epicure, is gone from his world, and is languishing in a dreary cell in Holloway Prison. In short, Mr Wilde, in a moment of weak-headedness, walked over the side of the mountain of fame and fell headlong from its height to the morass below, to lie there forgotten, neglected and abused.