The Project Gutenberg eBook, Poems of the Past and the Present, by Thomas Hardy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Poems of the Past and the Present Author: Thomas Hardy Release Date: January 24, 2015 [eBook #3168] [This file was first posted on January 30, 2001] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS OF THE PAST AND THE PRESENT***

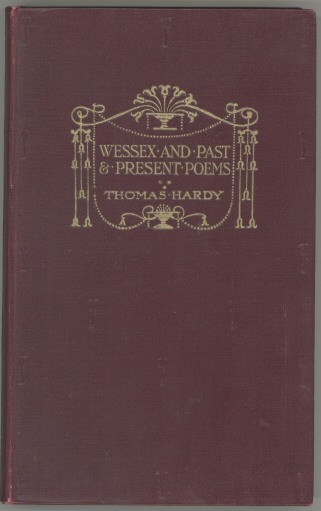

Transcribed from the 1919 Macmillan and Co. “Wessex Poems and Other Verses; Poems of the Past and the Present” edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

BY

THOMAS HARDY

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1919

“Wessex Poems”:

First Edition, Crown 8vo, 1898. New

Edition 1903.

First Pocket Edition June 1907. Reprinted

January 1909, 1913

“Poems, Past and

Present”: First edition 1901 (dated 1902)

Second Edition 1903. First Pocket Edition

June 1907

Reprinted January 1908, 1913, 1918, 1919

|

PAGE |

|

V.R. 1819–1901 |

||

WAR POEMS— |

||

|

Embarcation |

|

|

Departure |

|

|

The Colonel’s Soliloquy |

|

|

The Going of the Battery |

|

|

At the War Office |

|

|

A Christmas Ghost-Story |

|

|

The Dead Drummer |

|

|

A Wife in London |

|

|

The Souls of the Slain |

|

|

Song of the Soldiers’ Wives |

|

|

The Sick God |

|

POEMS OF PILGRIMAGE— |

||

|

Genoa and the Mediterranean |

|

|

Shelley’s Skylark |

|

|

In the Old Theatre, Fiesole |

|

|

Rome: on the Palatine |

|

|

,, Building a New Street in the Ancient Quarter |

|

|

,, The Vatican: Sala Delle Muse |

|

|

,, At the Pyramid of Cestius |

|

|

Lausanne: In Gibbon’s Old Garden |

|

|

Zermatt: To the Matterhorn |

|

|

The Bridge of Lodi |

|

|

On an Invitation to the United States |

|

|

The Mother Mourns |

|

|

“I said to Love” |

|

|

A Commonplace Day |

|

|

At a Lunar Eclipse |

|

|

The Lacking Sense |

|

|

To Life |

|

|

Doom and She |

|

|

The Problem |

|

|

The Subalterns |

|

|

The Sleep-worker |

|

|

The Bullfinches |

|

|

God-Forgotten |

|

|

The Bedridden Peasant to an Unknowing God |

|

|

By the Earth’s Corpse |

|

|

Mute Opinion |

|

|

To an Unborn Pauper Child |

|

|

To Flowers from Italy in Winter |

|

|

On a Fine Morning |

|

|

To Lizbie Browne |

|

|

Song of Hope |

|

|

The Well-Beloved |

|

|

Her Reproach |

|

|

The Inconsistent |

|

|

A Broken Appointment |

|

|

“Between us now” |

|

|

“How great my Grief” |

|

|

“I need not go” |

|

|

The Coquette, and After |

|

|

||

|

Long Plighted |

|

|

The Widow |

|

|

At a Hasty Wedding |

|

|

The Dream-Follower |

|

|

His Immortality |

|

|

The To-be-Forgotten |

|

|

Wives in the Sere |

|

|

The Superseded |

|

|

An August Midnight |

|

|

The Caged Thrush Freed and Home Again |

|

|

Birds at Winter Nightfall |

|

|

The Puzzled Game-Birds |

|

|

Winter in Durnover Field |

|

|

The Last Chrysanthemum |

|

|

The Darkling Thrush |

|

|

The Comet at Yalbury or Yell’ham |

|

|

Mad Judy |

|

|

A Wasted Illness |

|

|

A Man |

|

|

The Dame of Athelhall |

|

|

The Seasons of her Year |

|

|

The Milkmaid |

|

|

The Levelled Churchyard |

|

|

The Ruined Maid |

|

|

The Respectable Burgher on “the Higher Criticism” |

|

|

Architectural Masks |

|

|

The Tenant-for-Life |

|

|

||

|

The Tree: an Old Man’s Story |

|

|

Her Late Husband |

|

|

The Self-Unseeing |

|

|

De Profundis i. |

|

|

De Profundis ii. |

|

|

De Profundis iii. |

|

|

The Church-Builder |

|

|

The Lost Pyx: a Mediæval Legend |

|

|

Tess’s Lament |

|

|

The Supplanter: A Tale |

|

IMITATIONS, Etc.— |

||

|

Sapphic Fragment |

|

|

Catullus: xxxi |

|

|

After Schiller |

|

|

Song: From Heine |

|

|

From Victor Hugo |

|

|

Cardinal Bembo’s Epitaph on Raphael |

|

RETROSPECT— |

||

|

“I have Lived with Shades” |

|

|

Memory and I |

|

|

ΑΓΝΩΣΤΩ. ΘΕΩ |

|

Moments the

mightiest pass uncalendared,

And when the Absolute

In backward Time outgave the deedful word

Whereby all life is stirred:

“Let one be born and throned whose mould shall

constitute

The norm of every royal-reckoned attribute,”

No mortal knew or heard.

p.

232But in due days the purposed Life outshone—

Serene, sagacious, free;

—Her waxing seasons bloomed with deeds well

done,

And the world’s heart was

won . . .

Yet may the deed of hers most bright in eyes to be

Lie hid from ours—as in the All-One’s thought lay

she—

Till ripening years have run.

Sunday Night,

27th

January 1901.

Here, where

Vespasian’s legions struck the sands,

And Cerdic with his Saxons entered in,

And Henry’s army leapt afloat to win

Convincing triumphs over neighbour lands,

Vaster battalions press for further strands,

To argue in the self-same bloody mode

Which this late age of thought, and pact, and code,

Still fails to mend.—Now deckward tramp the bands,

p. 236Yellow

as autumn leaves, alive as spring;

And as each host draws out upon the sea

Beyond which lies the tragical To-be,

None dubious of the cause, none murmuring,

Wives, sisters, parents, wave white hands and

smile,

As if they knew not that they weep the while.

While the far

farewell music thins and fails,

And the broad bottoms rip the bearing brine—

All smalling slowly to the gray sea line—

And each significant red smoke-shaft pales,

Keen sense of severance everywhere prevails,

Which shapes the late long tramp of mounting men

To seeming words that ask and ask again:

“How long, O striving Teutons, Slavs, and Gaels

p. 238Must

your wroth reasonings trade on lives like these,

That are as puppets in a playing hand?—

When shall the saner softer polities

Whereof we dream, have play in each proud land,

And patriotism, grown Godlike, scorn to stand

Bondslave to realms, but circle earth and seas?”

“The quay

recedes. Hurrah! Ahead we go! . . .

It’s true I’ve been accustomed now to home,

And joints get rusty, and one’s limbs may grow

More fit to rest than roam.

“But I can stand as yet fair stress and

strain;

There’s not a little steel beneath the rust;

My years mount somewhat, but here’s to’t again!

And if I fall, I must.

p.

240“God knows that for myself I’ve scanty

care;

Past scrimmages have proved as much to all;

In Eastern lands and South I’ve had my share

Both of the blade and ball.

“And where those villains ripped me in

the flitch

With their old iron in my early time,

I’m apt at change of wind to feel a twitch,

Or at a change of clime.

“And what my mirror shows me in the

morning

Has more of blotch and wrinkle than of bloom;

My eyes, too, heretofore all glasses scorning,

Have just a touch of rheum . . .

“Now sounds ‘The Girl I’ve

left behind me,’—Ah,

The years, the ardours, wakened by that tune!

Time was when, with the crowd’s farewell

‘Hurrah!’

’Twould lift me to the moon.

p.

241“But now it’s late to leave behind me

one

Who if, poor soul, her man goes underground,

Will not recover as she might have done

In days when hopes abound.

“She’s waving from the wharfside,

palely grieving,

As down we draw . . . Her tears make little show,

Yet now she suffers more than at my leaving

Some twenty years ago.

“I pray those left at home will care for

her!

I shall come back; I have before; though when

The Girl you leave behind you is a grandmother,

Things may not be as then.”

I

O it was sad enough,

weak enough, mad enough—

Light in their loving as soldiers can be—

First to risk choosing them, leave alone losing them

Now, in far battle, beyond the South Sea! . . .

—Rain came down drenchingly; but we

unblenchingly

Trudged on beside them through mirk and through mire,

They stepping steadily—only too readily!—

Scarce as if stepping brought parting-time nigher.

III

Great guns were gleaming there, living things

seeming there,

Cloaked in their tar-cloths, upmouthed to the night;

Wheels wet and yellow from axle to felloe,

Throats blank of sound, but prophetic to sight.

IV

Gas-glimmers drearily, blearily, eerily

Lit our pale faces outstretched for one kiss,

While we stood prest to them, with a last quest to them

Not to court perils that honour could miss.

Sharp were those sighs of ours, blinded these

eyes of ours,

When at last moved away under the arch

All we loved. Aid for them each woman prayed for

them,

Treading back slowly the track of their march.

VI

Someone said: “Nevermore will they come:

evermore

Are they now lost to us.” O it was wrong!

Though may be hard their ways, some Hand will guard their

ways,

Bear them through safely, in brief time or long.

VII

—Yet, voices haunting us, daunting us,

taunting us,

Hint in the night-time when life beats are low

Other and graver things . . . Hold we to braver things,

Wait we, in trust, what Time’s fulness shall show.

I

Last year I called

this world of gain-givings

The darkest thinkable, and questioned sadly

If my own land could heave its pulse less gladly,

So charged it seemed with circumstance whence springs

The tragedy of things.

Yet at that censured time no heart was rent

Or feature blanched of parent, wife, or daughter

By hourly blazoned sheets of listed slaughter;

Death waited Nature’s wont; Peace smiled unshent

From Ind to Occident.

South of the Line,

inland from far Durban,

A mouldering soldier lies—your countryman.

Awry and doubled up are his gray bones,

And on the breeze his puzzled phantom moans

Nightly to clear Canopus: “I would know

By whom and when the All-Earth-gladdening Law

Of Peace, brought in by that Man Crucified,

Was ruled to be inept, and set aside?

p. 248And what

of logic or of truth appears

In tacking ‘Anno Domini’ to the years?

Near twenty-hundred livened thus have hied,

But tarries yet the Cause for which He died.”

Christmas-eve, 1899.

I

They throw in

Drummer Hodge, to rest

Uncoffined—just as found:

His landmark is a kopje-crest

That breaks the veldt around;

And foreign constellations west

Each night above his mound.

Young Hodge the Drummer never knew—

Fresh from his Wessex home—

The meaning of the broad Karoo,

The Bush, the dusty loam,

And why uprose to nightly view

Strange stars amid the gloam.

III

Yet portion of that unknown plain

Will Hodge for ever be;

His homely Northern breast and brain

Grow up a Southern tree.

And strange-eyed constellations reign

His stars eternally.

I

THE TRAGEDY

She sits in the

tawny vapour

That the City lanes have

uprolled,

Behind whose webby fold on fold

Like a waning taper

The street-lamp glimmers cold.

A messenger’s knock cracks smartly,

Flashed news is in her hand

Of meaning it dazes to

understand

p. 252Though

shaped so shortly:

He—has fallen—in the far South

Land . . .

II

THE IRONY

’Tis the morrow; the fog hangs

thicker,

The postman nears and goes:

A letter is brought whose lines

disclose

By the firelight flicker

His hand, whom the worm now knows:

Fresh—firm—penned in highest

feather—

Page-full of his hoped return,

And of home-planned jaunts by

brake and burn

In the summer weather,

And of new love that they would learn.

I

The thick lids of Night

closed upon me

Alone at the Bill

Of the Isle by the Race [253]—

Many-caverned, bald, wrinkled of face—

And with darkness and silence the spirit was on me

To brood and be still.

No wind fanned the flats of

the ocean,

Or promontory sides,

Or the ooze by the strand,

Or the bent-bearded slope of the land,

Whose base took its rest amid everlong motion

Of criss-crossing tides.

III

Soon from out of the

Southward seemed nearing

A whirr, as of wings

Waved by mighty-vanned flies,

Or by night-moths of measureless size,

And in softness and smoothness well-nigh beyond hearing

Of corporal things.

IV

And they bore to the bluff,

and alighted—

A dim-discerned train

Of sprites without mould,

Frameless souls none might touch or might

hold—

p. 255On the

ledge by the turreted lantern, farsighted

By men of the main.

V

And I heard them say

“Home!” and I knew them

For souls of the felled

On the earth’s nether

bord

Under Capricorn, whither they’d warred,

And I neared in my awe, and gave heedfulness to them

With breathings inheld.

VI

Then, it seemed, there

approached from the northward

A senior soul-flame

Of the like filmy hue:

And he met them and spake: “Is it you,

O my men?” Said they, “Aye! We bear

homeward and hearthward

To list to our fame!”

“I’ve flown there

before you,” he said then:

“Your households are

well;

But—your kin linger less

On your glory arid war-mightiness

Than on dearer things.”—“Dearer?” cried

these from the dead then,

“Of what do they

tell?”

VIII

“Some mothers muse

sadly, and murmur

Your doings as boys—

Recall the quaint ways

Of your babyhood’s innocent days.

Some pray that, ere dying, your faith had grown firmer,

And higher your joys.

IX

“A father broods:

‘Would I had set him

To some humble trade,

And so slacked his high fire,

And his passionate martial desire;

p. 257Had told

him no stories to woo him and whet him

To this due crusade!”

X

“And, General, how hold

out our sweethearts,

Sworn loyal as doves?”

—“Many mourn; many

think

It is not unattractive to prink

Them in sables for heroes. Some fickle and fleet

hearts

Have found them new

loves.”

XI

“And our wives?”

quoth another resignedly,

“Dwell they on our

deeds?”

—“Deeds of home; that

live yet

Fresh as new—deeds of fondness or fret;

Ancient words that were kindly expressed or unkindly,

These, these have their

heeds.”

—“Alas! then it

seems that our glory

Weighs less in their thought

Than our old homely acts,

And the long-ago commonplace facts

Of our lives—held by us as scarce part of our story,

And rated as nought!”

XIII

Then bitterly some:

“Was it wise now

To raise the tomb-door

For such knowledge?

Away!”

But the rest: “Fame we prized till to-day;

Yet that hearts keep us green for old kindness we prize now

A thousand times more!”

XIV

Thus speaking, the trooped

apparitions

Began to disband

And resolve them in two:

Those whose record was lovely and true

p. 259Bore to

northward for home: those of bitter traditions

Again left the land,

XV

And, towering to seaward in

legions,

They paused at a spot

Overbending the Race—

That engulphing, ghast, sinister place—

Whither headlong they plunged, to the fathomless regions

Of myriads forgot.

XVI

And the spirits of those who

were homing

Passed on, rushingly,

Like the Pentecost Wind;

And the whirr of their wayfaring thinned

And surceased on the sky, and but left in the gloaming

Sea-mutterings and me.

December 1899.

I

At last! In

sight of home again,

Of home again;

No more to range and roam again

As at that bygone time?

No more to go away from us

And stay from us?—

Dawn, hold not long the day from us,

But quicken it to prime!

Now all the town shall ring to them,

Shall ring to them,

And we who love them cling to them

And clasp them joyfully;

And cry, “O much we’ll do for you

Anew for you,

Dear Loves!—aye, draw and hew for you,

Come back from oversea.”

III

Some told us we should meet no more,

Should meet no more;

Should wait, and wish, but greet no more

Your faces round our fires;

That, in a while, uncharily

And drearily

Men gave their lives—even wearily,

Like those whom living tires.

And now you are nearing home again,

Dears, home again;

No more, may be, to roam again

As at that bygone time,

Which took you far away from us

To stay from us;

Dawn, hold not long the day from us,

But quicken it to prime!

I

In

days when men had joy of war,

A God of Battles sped each mortal jar;

The peoples pledged him heart and hand,

From Israel’s land to isles afar.

II

His crimson form, with clang

and chime,

Flashed on each murk and murderous meeting-time,

p.

264And kings invoked, for rape and raid,

His fearsome aid in rune and rhyme.

III

On bruise and blood-hole,

scar and seam,

On blade and bolt, he flung his fulgid beam:

His haloes rayed the very gore,

And corpses wore his glory-gleam.

IV

Often an early King or

Queen,

And storied hero onward, knew his sheen;

’Twas glimpsed by Wolfe, by Ney anon,

And Nelson on his blue demesne.

V

But new light spread.

That god’s gold nimb

And blazon have waned dimmer and more dim;

Even his flushed form begins to fade,

Till but a shade is left of him.

That modern meditation

broke

His spell, that penmen’s pleadings dealt a stroke,

Say some; and some that crimes too dire

Did much to mire his crimson cloak.

VII

Yea, seeds of crescive

sympathy

Were sown by those more excellent than he,

Long known, though long contemned till

then—

The gods of men in amity.

VIII

Souls have grown seers, and

thought out-brings

The mournful many-sidedness of things

With foes as friends, enfeebling ires

And fury-fires by gaingivings!

IX

He scarce impassions

champions now;

They do and dare, but tensely—pale of brow;

p.

266And would they fain uplift the arm

Of that faint form they know not how.

X

Yet wars arise, though zest

grows cold;

Wherefore, at whiles, as ’twere in ancient mould

He looms, bepatched with paint and lath;

But never hath he seemed the old!

XI

Let men rejoice, let men

deplore.

The lurid Deity of heretofore

Succumbs to one of saner nod;

The Battle-god is god no more.

O epic-famed, god-haunted Central Sea,

Heave careless of the deep wrong done to thee

When from Torino’s track I saw thy face first flash on

me.

p. 270And multimarbled Genova the

Proud,

Gleam all unconscious how, wide-lipped,

up-browed,

I first beheld thee clad—not as the Beauty but the

Dowd.

Out from a deep-delved way my

vision lit

On housebacks pink, green, ochreous—where a

slit

Shoreward ’twixt row and row revealed the classic blue

through it.

And thereacross waved

fishwives’ high-hung smocks,

Chrome kerchiefs, scarlet hose, darned

underfrocks;

Since when too oft my dreams of thee, O Queen, that frippery

mocks:

Whereat I grieve, Superba! .

. . Afterhours

Within Palazzo Doria’s orange bowers

Went far to mend these marrings of thy soul-subliming powers.

p. 271But, Queen, such squalid undress

none should see,

Those dream-endangering eyewounds no more be

Where lovers first behold thy form in pilgrimage to thee.

Somewhere afield

here something lies

In Earth’s oblivious eyeless trust

That moved a poet to prophecies—

A pinch of unseen, unguarded dust

The dust of the lark that Shelley heard,

And made immortal through times to be;—

Though it only lived like another bird,

And knew not its immortality.

p.

273Lived its meek life; then, one day, fell—

A little ball of feather and bone;

And how it perished, when piped farewell,

And where it wastes, are alike unknown.

Maybe it rests in the loam I view,

Maybe it throbs in a myrtle’s green,

Maybe it sleeps in the coming hue

Of a grape on the slopes of yon inland scene.

Go find it, faeries, go and find

That tiny pinch of priceless dust,

And bring a casket silver-lined,

And framed of gold that gems encrust;

And we will lay it safe therein,

And consecrate it to endless time;

For it inspired a bard to win

Ecstatic heights in thought and rhyme.

I traced the Circus

whose gray stones incline

Where Rome and dim Etruria interjoin,

Till came a child who showed an ancient coin

That bore the image of a Constantine.

She lightly passed; nor did she once opine

How, better than all books, she had raised for me

p. 275In swift

perspective Europe’s history

Through the vast years of Cæsar’s sceptred line.

For in my distant plot of English loam

’Twas but to delve, and straightway there to find

Coins of like impress. As with one half blind

Whom common simples cure, her act flashed home

In that mute moment to my opened mind

The power, the pride, the reach of perished Rome.

We walked where

Victor Jove was shrined awhile,

And passed to Livia’s rich red mural show,

Whence, thridding cave and Criptoportico,

We gained Caligula’s dissolving pile.

And each ranked ruin tended to beguile

The outer sense, and shape itself as though

p. 277It wore

its marble hues, its pristine glow

Of scenic frieze and pompous peristyle.

When lo, swift hands, on strings nigh

over-head,

Began to melodize a waltz by Strauss:

It stirred me as I stood, in Cæsar’s house,

Raised the old routs Imperial lyres had led,

And blended pulsing life with lives long

done,

Till Time seemed fiction, Past and Present one.

These numbered

cliffs and gnarls of masonry

Outskeleton Time’s central city, Rome;

Whereof each arch, entablature, and dome

Lies bare in all its gaunt anatomy.

And cracking frieze and rotten metope

Express, as though they were an open tome

p.

279Top-lined with caustic monitory gnome;

“Dunces, Learn here to spell Humanity!”

And yet within these ruins’ very shade

The singing workmen shape and set and join

Their frail new mansion’s stuccoed cove and quoin

With no apparent sense that years abrade,

Though each rent wall their feeble works invade

Once shamed all such in power of pier and groin.

I sat in the

Muses’ Hall at the mid of the day,

And it seemed to grow still, and the people to pass away,

And the chiselled shapes to combine in a haze of sun,

Till beside a Carrara column there gleamed forth One.

p.

281She was nor this nor that of those beings divine,

But each and the whole—an essence of all the Nine;

With tentative foot she neared to my halting-place,

A pensive smile on her sweet, small, marvellous face.

“Regarded so long, we render thee

sad?” said she.

“Not you,” sighed I, “but my own

inconstancy!

I worship each and each; in the morning one,

And then, alas! another at sink of sun.

“To-day my soul clasps Form; but where is

my troth

Of yesternight with Tune: can one cleave to both?”

—“Be not perturbed,” said she.

“Though apart in fame,

As I and my sisters are one, those, too, are the same.

p.

282—“But my loves go further—to Story,

and Dance, and Hymn,

The lover of all in a sun-sweep is fool to whim—

Is swayed like a river-weed as the ripples run!”

—“Nay, wight, thou sway’st not. These are

but phases of one;

“And that one is I; and I am projected

from thee,

One that out of thy brain and heart thou causest to be—

Extern to thee nothing. Grieve not, nor thyself becall,

Woo where thou wilt; and rejoice thou canst love at

all!”

Who, then, was Cestius,

And what is he to me?—

Amid thick thoughts and memories multitudinous

One thought alone brings he.

p. 284I can

recall no word

Of anything he did;

For me he is a man who died and was interred

To leave a pyramid

Whose

purpose was exprest

Not with its first design,

Nor till, far down in Time, beside it found their rest

Two countrymen of mine.

Cestius in

life, maybe,

Slew, breathed out threatening;

I know not. This I know: in death all silently

He does a kindlier thing,

In

beckoning pilgrim feet

With marble finger high

To where, by shadowy wall and history-haunted street,

Those matchless singers lie . .

.

p. 285—Say,

then, he lived and died

That stones which bear his name

Should mark, through Time, where two immortal Shades abide;

It is an ample fame.

(The 110th anniversary of the completion of the “Decline and Fall” at the same hour and place)

A spirit seems to pass,

Formal in pose, but grave and grand withal:

He contemplates a volume stout and tall,

And far lamps fleck him through the thin acacias.

p. 287Anon the

book is closed,

With “It is finished!” And at the

alley’s end

He turns, and soon on me his glances bend;

And, as from earth, comes speech—small, muted, yet

composed.

“How

fares the Truth now?—Ill?

—Do pens but slily further her advance?

May one not speed her but in phrase askance?

Do scribes aver the Comic to be Reverend still?

“Still

rule those minds on earth

At whom sage Milton’s wormwood words were

hurled:

‘Truth like a bastard comes into the

world

Never without ill-fame to him who gives her

birth’?”

Thirty-two years

since, up against the sun,

Seven shapes, thin atomies to lower sight,

Labouringly leapt and gained thy gabled height,

And four lives paid for what the seven had won.

p.

289They were the first by whom the deed was done,

And when I look at thee, my mind takes flight

To that day’s tragic feat of manly might,

As though, till then, of history thou hadst none.

Yet ages ere men topped thee, late and soon

Thou watch’dst each night the planets lift and lower;

Thou gleam’dst to Joshua’s pausing sun and moon,

And brav’dst the tokening sky when Cæsar’s

power

Approached its bloody end: yea, saw’st that Noon

When darkness filled the earth till the ninth hour.

I

When of tender mind

and body

I was moved by minstrelsy,

And that strain “The Bridge of Lodi”

Brought a strange delight to me.

In the battle-breathing jingle

Of its forward-footing tune

I could see the armies mingle,

And the columns cleft and hewn

III

On that far-famed spot by Lodi

Where Napoleon clove his way

To his fame, when like a god he

Bent the nations to his sway.

IV

Hence the tune came capering to me

While I traced the Rhone and Po;

Nor could Milan’s Marvel woo me

From the spot englamoured so.

V

And to-day, sunlit and smiling,

Here I stand upon the scene,

With its saffron walls, dun tiling,

And its meads of maiden green,

Even as when the trackway thundered

With the charge of grenadiers,

And the blood of forty hundred

Splashed its parapets and piers . . .

VII

Any ancient crone I’d toady

Like a lass in young-eyed prime,

Could she tell some tale of Lodi

At that moving mighty time.

VIII

So, I ask the wives of Lodi

For traditions of that day;

But alas! not anybody

Seems to know of such a fray.

IX

And they heed but transitory

Marketings in cheese and meat,

Till I judge that Lodi’s story

Is extinct in Lodi’s street.

Yet while here and there they thrid them

In their zest to sell and buy,

Let me sit me down amid them

And behold those thousands die . . .

XI

—Not a creature cares in Lodi

How Napoleon swept each arch,

Or where up and downward trod he,

Or for his memorial March!

XII

So that wherefore should I be here,

Watching Adda lip the lea,

When the whole romance to see here

Is the dream I bring with me?

XIII

And why sing “The Bridge of

Lodi”

As I sit thereon and swing,

When none shows by smile or nod he

Guesses why or what I sing? . . .

Since all Lodi, low and head ones,

Seem to pass that story by,

It may be the Lodi-bred ones

Rate it truly, and not I.

XV

Once engrossing Bridge of Lodi,

Is thy claim to glory gone?

Must I pipe a palinody,

Or be silent thereupon?

XVI

And if here, from strand to steeple,

Be no stone to fame the fight,

Must I say the Lodi people

Are but viewing crime aright?

XVII

Nay; I’ll sing “The Bridge of

Lodi”—

That long-loved, romantic thing,

Though none show by smile or nod he

Guesses why and what I sing!

I

My ardours for

emprize nigh lost

Since Life has bared its bones to me,

I shrink to seek a modern coast

Whose riper times have yet to be;

Where the new regions claim them free

From that long drip of human tears

Which peoples old in tragedy

Have left upon the centuried years.

For, wonning in these ancient lands,

Enchased and lettered as a tomb,

And scored with prints of perished hands,

And chronicled with dates of doom,

Though my own Being bear no bloom

I trace the lives such scenes enshrine,

Give past exemplars present room,

And their experience count as mine.

When

mid-autumn’s moan shook the night-time,

And sedges were horny,

And summer’s green wonderwork faltered

On leaze and in lane,

I fared Yell’ham-Firs way, where dimly

Came wheeling around me

Those phantoms obscure and insistent

That shadows unchain.

p.

300Till airs from the needle-thicks brought me

A low lamentation,

As ’twere of a tree-god disheartened,

Perplexed, or in pain.

And, heeding, it awed me to gather

That Nature herself there

Was breathing in aërie accents,

With dirgeful refrain,

Weary plaint that Mankind, in these late

days,

Had grieved her by holding

Her ancient high fame of perfection

In doubt and disdain . . .

—“I had not proposed me a

Creature

(She soughed) so excelling

All else of my kingdom in compass

And brightness of brain

“As to read my defects with a

god-glance,

Uncover each vestige

Of old inadvertence, annunciate

Each flaw and each stain!

p.

301“My purpose went not to develop

Such insight in Earthland;

Such potent appraisements affront me,

And sadden my reign!

“Why loosened I olden control here

To mechanize skywards,

Undeeming great scope could outshape in

A globe of such grain?

“Man’s mountings of mind-sight I

checked not,

Till range of his vision

Has topped my intent, and found blemish

Throughout my domain.

“He holds as inept his own

soul-shell—

My deftest achievement—

Contemns me for fitful inventions

Ill-timed and inane:

“No more sees my sun as a Sanct-shape,

My moon as the Night-queen,

My stars as august and sublime ones

That influences rain:

p.

302“Reckons gross and ignoble my teaching,

Immoral my story,

My love-lights a lure, that my species

May gather and gain.

“‘Give me,’ he has said,

‘but the matter

And means the gods lot her,

My brain could evolve a creation

More seemly, more sane.’

—“If ever a naughtiness seized

me

To woo adulation

From creatures more keen than those crude ones

That first formed my train—

“If inly a moment I murmured,

‘The simple praise sweetly,

But sweetlier the sage’—and did rashly

Man’s vision unrein,

“I rue it! . . . His guileless

forerunners,

Whose brains I could blandish,

p. 303To

measure the deeps of my mysteries

Applied them in vain.

“From them my waste aimings and futile

I subtly could cover;

‘Every best thing,’ said they, ‘to best

purpose

Her powers preordain.’—

“No more such! . . . My species are

dwindling,

My forests grow barren,

My popinjays fail from their tappings,

My larks from their strain.

“My leopardine beauties are rarer,

My tusky ones vanish,

My children have aped mine own slaughters

To quicken my wane.

“Let me grow, then, but mildews and

mandrakes,

And slimy distortions,

Let nevermore things good and lovely

To me appertain;

p.

304“For Reason is rank in my temples,

And Vision unruly,

And chivalrous laud of my cunning

Is heard not again!”

I said to Love,

“It is not now as in old days

When men adored thee and thy ways

All else above;

Named thee the Boy, the Bright, the One

Who spread a heaven beneath the sun,”

I said to Love.

p. 306I said to

him,

“We now know more of thee than then;

We were but weak in judgment when,

With hearts abrim,

We clamoured thee that thou would’st please

Inflict on us thine agonies,”

I said to him.

I said to

Love,

“Thou art not young, thou art not fair,

No faery darts, no cherub air,

Nor swan, nor dove

Are thine; but features pitiless,

And iron daggers of distress,”

I said to Love.

“Depart

then, Love! . . .

—Man’s race shall end, dost threaten thou?

The age to come the man of now

Know nothing of?—

We fear not such a threat from thee;

We are too old in apathy!

Mankind shall cease.—So let it be,”

I said to Love.

The day is turning ghost,

And scuttles from the kalendar in fits and furtively,

To join the anonymous host

Of those that throng oblivion; ceding his place, maybe,

To one of like degree.

p. 308I part the fire-gnawed logs,

Rake forth the embers, spoil the busy flames, and lay the ends

Upon the shining dogs;

Further and further from the nooks the twilight’s stride

extends,

And beamless black impends.

Nothing of tiniest worth

Have I wrought, pondered, planned; no one thing asking blame or

praise,

Since the pale corpse-like birth

Of this diurnal unit, bearing blanks in all its rays—

Dullest of dull-hued Days!

Wanly upon the panes

The rain slides as have slid since morn my colourless thoughts;

and yet

Here, while Day’s presence wanes,

And over him the sepulchre-lid is slowly lowered and set,

He wakens my regret.

p. 309Regret—though nothing dear

That I wot of, was toward in the wide world at his prime,

Or bloomed elsewhere than here,

To die with his decease, and leave a memory sweet, sublime,

Or mark him out in Time . . .

—Yet, maybe, in some

soul,

In some spot undiscerned on sea or land, some impulse rose,

Or some intent upstole

Of that enkindling ardency from whose maturer glows

The world’s amendment flows;

But which, benumbed at

birth

By momentary chance or wile, has missed its hope to be

Embodied on the earth;

And undervoicings of this loss to man’s futurity

May wake regret in me.

Thy shadow, Earth,

from Pole to Central Sea,

Now steals along upon the Moon’s meek shine

In even monochrome and curving line

Of imperturbable serenity.

How shall I link such sun-cast symmetry

With the torn troubled form I know as thine,

p. 311That

profile, placid as a brow divine,

With continents of moil and misery?

And can immense Mortality but throw

So small a shade, and Heaven’s high human scheme

Be hemmed within the coasts yon arc implies?

Is such the stellar gauge of earthly show,

Nation at war with nation, brains that teem,

Heroes, and women fairer than the skies?

Scene.—A sad-coloured landscape, Waddon Vale

I

“O Time,

whence comes the Mother’s moody look amid her labours,

As of one who all unwittingly has wounded where she

loves?

Why weaves she not her world-webs to according lutes

and tabors,

With nevermore this too remorseful air upon her face,

As of angel fallen from

grace?”

—“Her look is but her story:

construe not its symbols keenly:

In her wonderworks yea surely has she wounded where

she loves.

The sense of ills misdealt for blisses blanks the

mien most queenly,

Self-smitings kill self-joys; and everywhere beneath the sun

Such deeds her hands have

done.”

III

—“And how explains thy Ancient Mind

her crimes upon her creatures,

These fallings from her fair beginnings, woundings

where she loves,

Into her would-be perfect motions, modes, effects,

and features

Admitting cramps, black humours, wan decay, and baleful

blights,

Distress into delights?”

—“Ah! know’st thou not her

secret yet, her vainly veiled deficience,

Whence it comes that all unwittingly she wounds the

lives she loves?

That sightless are those orbs of hers?—which

bar to her omniscience

Brings those fearful unfulfilments, that red ravage through her

zones

Whereat all creation groans.

V

“She whispers it in each pathetic

strenuous slow endeavour,

When in mothering she unwittingly sets wounds on

what she loves;

Yet her primal doom pursues her, faultful, fatal is

she ever;

Though so deft and nigh to vision is her facile finger-touch

That the seers marvel much.

“Deal, then, her groping skill no scorn,

no note of malediction;

Not long on thee will press the hand that hurts the

lives it loves;

And while she dares dead-reckoning on, in darkness

of affliction,

Assist her where thy creaturely dependence can or may,

For thou art of her

clay.”

O life with the sad seared face,

I weary of seeing thee,

And thy draggled cloak, and thy hobbling pace,

And thy too-forced pleasantry!

I know what thou

would’st tell

Of Death, Time, Destiny—

I have known it long, and know, too, well

What it all means for me.

p. 317But canst thou not array

Thyself in rare disguise,

And feign like truth, for one mad day,

That Earth is Paradise?

I’ll tune me to the

mood,

And mumm with thee till eve;

And maybe what as interlude

I feign, I shall believe!

I

There dwells a mighty pair—

Slow, statuesque, intense—

Amid the vague Immense:

None can their chronicle declare,

Nor why they be, nor whence.

Mother of all things made,

Matchless in artistry,

Unlit with sight is she.—

And though her ever well-obeyed

Vacant of feeling he.

III

The Matron mildly

asks—

A throb in every word—

“Our clay-made creatures, lord,

How fare they in their mortal tasks

Upon Earth’s bounded bord?

IV

“The fate of those I

bear,

Dear lord, pray turn and view,

And notify me true;

Shapings that eyelessly I dare

Maybe I would undo.

V

“Sometimes from lairs

of life

Methinks I catch a groan,

Or multitudinous moan,

p. 320As

though I had schemed a world of strife,

Working by touch alone.”

VI

“World-weaver!”

he replies,

“I scan all thy domain;

But since nor joy nor pain

Doth my clear substance recognize,

I read thy realms in vain.

VII

“World-weaver! what

is Grief?

And what are Right, and Wrong,

And Feeling, that belong

To creatures all who owe thee fief?

What worse is Weak than Strong?” . . .

VIII

—Unlightened, curious,

meek,

She broods in sad surmise . . .

—Some say they have heard her sighs

On Alpine height or Polar peak

When the night tempests rise.

Shall we conceal the Case, or tell

it—

We who believe the evidence?

Here and there the watch-towers knell it

With a sullen significance,

Heard of the few who hearken intently and carry an eagerly

upstrained sense.

p. 322Hearts that are happiest hold not by

it;

Better we let, then, the old view

reign;

Since there is peace in it, why decry it?

Since there is comfort, why

disdain?

Note not the pigment the while that the painting determines

humanity’s joy and pain!

I

“Poor

wanderer,” said the leaden sky,

“I fain would lighten thee,

But there be laws in force on high

Which say it must not be.”

II

—“I would not freeze thee, shorn

one,” cried

The North, “knew I but how

p. 324To warm

my breath, to slack my stride;

But I am ruled as thou.”

III

—“To-morrow I attack thee,

wight,”

Said Sickness. “Yet I swear

I bear thy little ark no spite,

But am bid enter there.”

IV

—“Come hither, Son,” I heard

Death say;

“I did not will a grave

Should end thy pilgrimage to-day,

But I, too, am a slave!”

V

We smiled upon each other then,

And life to me wore less

That fell contour it wore ere when

They owned their passiveness.

When wilt thou wake,

O Mother, wake and see—

As one who, held in trance, has laboured long

By vacant rote and prepossession strong—

The coils that thou hast wrought unwittingly;

Wherein have place, unrealized by thee,

Fair growths, foul cankers, right enmeshed with wrong,

Strange orchestras of victim-shriek and song,

And curious blends of ache and ecstasy?—

p.

326Should that morn come, and show thy opened eyes

All that Life’s palpitating tissues feel,

How wilt thou bear thyself in thy surprise?—

Wilt thou destroy, in one wild shock of

shame,

Thy whole high heaving firmamental frame,

Or patiently adjust, amend, and heal?

Brother Bulleys, let us sing

From the dawn till evening!—

For we know not that we go not

When the day’s pale pinions fold

Unto those who sang of old.

When I flew to Blackmoor

Vale,

Whence the green-gowned faeries hail,

Roosting near them I could hear them

Speak of queenly Nature’s ways,

Means, and moods,—well known to fays.

p. 328All we creatures, nigh and far

(Said they there), the Mother’s are:

Yet she never shows endeavour

To protect from warrings wild

Bird or beast she calls her child.

Busy in her handsome house

Known as Space, she falls a-drowse;

Yet, in seeming, works on dreaming,

While beneath her groping hands

Fiends make havoc in her bands.

How her hussif’ry

succeeds

She unknows or she unheeds,

All things making for Death’s taking!

—So the green-gowned faeries say

Living over Blackmoor way.

Come then, brethren, let us

sing,

From the dawn till evening!—

For we know not that we go not

When the day’s pale pinions fold

Unto those who sang of old.

I towered far, and lo! I stood within

The presence of the Lord Most High,

Sent thither by the sons of earth, to win

Some answer to their cry.

—“The Earth,

say’st thou? The Human race?

By Me created? Sad its lot?

Nay: I have no remembrance of such place:

Such world I fashioned

not.”—

p. 330—“O Lord, forgive me

when I say

Thou spak’st the word, and mad’st it

all.”—

“The Earth of men—let me bethink me . . . Yea!

I dimly do recall

“Some tiny sphere I

built long back

(Mid millions of such shapes of mine)

So named . . . It perished, surely—not a wrack

Remaining, or a sign?

“It lost my interest

from the first,

My aims therefor succeeding ill;

Haply it died of doing as it durst?”—

“Lord, it existeth

still.”—

“Dark, then, its

life! For not a cry

Of aught it bears do I now hear;

Of its own act the threads were snapt whereby

Its plaints had reached mine

ear.

“It used to ask for

gifts of good,

Till came its severance self-entailed,

p. 331When

sudden silence on that side ensued,

And has till now prevailed.

“All other orbs have

kept in touch;

Their voicings reach me speedily:

Thy people took upon them overmuch

In sundering them from me!

“And it is

strange—though sad enough—

Earth’s race should think that one whose

call

Frames, daily, shining spheres of flawless stuff

Must heed their tainted ball! . .

.

“But say’st thou

’tis by pangs distraught,

And strife, and silent suffering?—

Deep grieved am I that injury should be wrought

Even on so poor a thing!

“Thou should’st

have learnt that Not to Mend

For Me could mean but Not to Know:

Hence, Messengers! and straightway put an end

To what men undergo.” . .

.

p. 332Homing at dawn, I thought to see

One of the Messengers standing by.

—Oh, childish thought! . . . Yet oft it comes to me

When trouble hovers nigh.

Much wonder

I—here long low-laid—

That this dead wall should be

Betwixt the Maker and the made,

Between Thyself and me!

For, say one puts a child to nurse,

He eyes it now and then

To know if better ’tis, or worse,

And if it mourn, and when.

p.

334But Thou, Lord, giv’st us men our clay

In helpless bondage thus

To Time and Chance, and seem’st straightway

To think no more of us!

That some disaster cleft Thy scheme

And tore us wide apart,

So that no cry can cross, I deem;

For Thou art mild of heart,

And would’st not shape and shut us in

Where voice can not he heard:

’Tis plain Thou meant’st that we should win

Thy succour by a word.

Might but Thy sense flash down the skies

Like man’s from clime to clime,

Thou would’st not let me agonize

Through my remaining time;

But, seeing how much Thy creatures

bear—

Lame, starved, or maimed, or blind—

Thou’dst heal the ills with quickest care

Of me and all my kind.

p.

335Then, since Thou mak’st not these things be,

But these things dost not know,

I’ll praise Thee as were shown to me

The mercies Thou would’st show!

I

“O Lord, why grievest Thou?—

Since Life has ceased to be

Upon this globe, now cold

As lunar land and sea,

And humankind, and fowl, and fur

Are gone eternally,

All is the same to Thee as ere

They knew mortality.”

“O Time,” replied the Lord,

“Thou read’st me ill, I ween;

Were all the same, I should not grieve

At that late earthly scene,

Now blestly past—though planned by me

With interest close and keen!—

Nay, nay: things now are not the same

As they have earlier been.

III

“Written indelibly

On my eternal mind

Are all the wrongs endured

By Earth’s poor patient kind,

Which my too oft unconscious hand

Let enter undesigned.

No god can cancel deeds foredone,

Or thy old coils unwind!

IV

“As when, in

Noë’s days,

I whelmed the plains with sea,

p.

338So at this last, when flesh

And herb but fossils be,

And, all extinct, their piteous dust

Revolves obliviously,

That I made Earth, and life, and man,

It still repenteth me!”

I

I traversed a

dominion

Whose spokesmen spake out strong

Their purpose and opinion

Through pulpit, press, and song.

I scarce had means to note there

A large-eyed few, and dumb,

Who thought not as those thought there

That stirred the heat and hum.

When, grown a Shade, beholding

That land in lifetime trode,

To learn if its unfolding

Fulfilled its clamoured code,

I saw, in web unbroken,

Its history outwrought

Not as the loud had spoken,

But as the mute had thought.

I

Breathe not, hid Heart: cease silently,

And though thy birth-hour beckons thee,

Sleep the long sleep:

The Doomsters heap

Travails and teens around us here,

And Time-wraiths turn our songsingings to fear.

Hark, how the peoples surge

and sigh,

And laughters fail, and greetings die:

Hopes dwindle; yea,

Faiths waste away,

Affections and enthusiasms numb;

Thou canst not mend these things if thou dost come.

III

Had I the ear of

wombèd souls

Ere their terrestrial chart unrolls,

And thou wert free

To cease, or be,

Then would I tell thee all I know,

And put it to thee: Wilt thou take Life so?

IV

Vain vow! No hint of

mine may hence

To theeward fly: to thy locked sense

Explain none can

Life’s pending plan:

Thou wilt thy ignorant entry make

Though skies spout fire and blood and nations quake.

Fain would I, dear, find some

shut plot

Of earth’s wide wold for thee, where not

One tear, one qualm,

Should break the calm.

But I am weak as thou and bare;

No man can change the common lot to rare.

VI

Must come and bide. And

such are we—

Unreasoning, sanguine, visionary—

That I can hope

Health, love, friends, scope

In full for thee; can dream thou’lt find

Joys seldom yet attained by humankind!

Sunned in the South,

and here to-day;

—If all organic things

Be sentient, Flowers, as some men say,

What are your ponderings?

How can you stay, nor vanish quite

From this bleak spot of thorn,

And birch, and fir, and frozen white

Expanse of the forlorn?

p.

345Frail luckless exiles hither brought!

Your dust will not regain

Old sunny haunts of Classic thought

When you shall waste and wane;

But mix with alien earth, be lit

With frigid Boreal flame,

And not a sign remain in it

To tell men whence you came.

Whence comes

Solace?—Not from seeing

What is doing, suffering, being,

Not from noting Life’s conditions,

Nor from heeding Time’s monitions;

But in cleaving to the Dream,

And in gazing at the gleam

Whereby gray things golden seem.

Thus do I this heyday, holding

Shadows but as lights unfolding,

As no specious show this moment

With its irisèd embowment;

But as nothing other than

Part of a benignant plan;

Proof that earth was made for man.

February 1899.

I

Dear Lizbie

Browne,

Where are you now?

In sun, in rain?—

Or is your brow

Past joy, past pain,

Dear Lizbie Browne?

Sweet Lizbie Browne

How you could smile,

How you could sing!—

How archly wile

In glance-giving,

Sweet Lizbie Browne!

III

And, Lizbie Browne,

Who else had hair

Bay-red as yours,

Or flesh so fair

Bred out of doors,

Sweet Lizbie Browne?

IV

When, Lizbie Browne,

You had just begun

To be endeared

By stealth to one,

You disappeared

My Lizbie Browne!

Ay, Lizbie Browne,

So swift your life,

And mine so slow,

You were a wife

Ere I could show

Love, Lizbie Browne.

VI

Still, Lizbie Browne,

You won, they said,

The best of men

When you were wed . . .

Where went you then,

O Lizbie Browne?

VII

Dear Lizbie Browne,

I should have thought,

“Girls ripen fast,”

And coaxed and caught

You ere you passed,

Dear Lizbie Browne!

But, Lizbie Browne,

I let you slip;

Shaped not a sign;

Touched never your lip

With lip of mine,

Lost Lizbie Browne!

IX

So, Lizbie Browne,

When on a day

Men speak of me

As not, you’ll say,

“And who was he?”—

Yes, Lizbie Browne!

O sweet

To-morrow!—

After to-day

There will away

This sense of sorrow.

Then let us borrow

Hope, for a gleaming

Soon will be streaming,

Dimmed by no gray—

No gray!

p.

353While the winds wing us

Sighs from The Gone,

Nearer to dawn

Minute-beats bring us;

When there will sing us

Larks of a glory

Waiting our story

Further anon—

Anon!

Doff the black token,

Don the red shoon,

Right and retune

Viol-strings broken;

Null the words spoken

In speeches of rueing,

The night cloud is hueing,

To-morrow shines soon—

Shines soon!

I wayed by star and planet shine

Towards the dear one’s home

At Kingsbere, there to make her mine

When the next sun upclomb.

I edged the ancient hill and wood

Beside the Ikling Way,

Nigh where the Pagan temple stood

In the world’s earlier day.

p.

355And as I quick and quicker walked

On gravel and on green,

I sang to sky, and tree, or talked

Of her I called my queen.

—“O faultless is her dainty

form,

And luminous her mind;

She is the God-created norm

Of perfect womankind!”

A shape whereon one star-blink gleamed

Glode softly by my side,

A woman’s; and her motion seemed

The motion of my bride.

And yet methought she’d drawn

erstwhile

Adown the ancient leaze,

Where once were pile and peristyle

For men’s idolatries.

—“O maiden lithe and lone, what

may

Thy name and lineage be,

Who so resemblest by this ray

My darling?—Art thou she?”

p.

356The Shape: “Thy bride remains within

Her father’s grange and grove.”

—“Thou speakest rightly,” I broke in,

“Thou art not she I love.”

—“Nay: though thy bride remains

inside

Her father’s walls,” said she,

“The one most dear is with thee here,

For thou dost love but me.”

Then I: “But she, my only choice,

Is now at Kingsbere Grove?”

Again her soft mysterious voice:

“I am thy only Love.”

Thus still she vouched, and still I said,

“O sprite, that cannot be!” . . .

It was as if my bosom bled,

So much she troubled me.

The sprite resumed: “Thou hast

transferred

To her dull form awhile

My beauty, fame, and deed, and word,

My gestures and my smile.

p.

357“O fatuous man, this truth infer,

Brides are not what they seem;

Thou lovest what thou dreamest her;

I am thy very dream!”

—“O then,” I answered

miserably,

Speaking as scarce I knew,

“My loved one, I must wed with thee

If what thou say’st be true!”

She, proudly, thinning in the gloom:

“Though, since troth-plight began,

I’ve ever stood as bride to groom,

I wed no mortal man!”

Thereat she vanished by the Cross

That, entering Kingsbere town,

The two long lanes form, near the fosse

Below the faneless Down.

—When I arrived and met my bride,

Her look was pinched and thin,

As if her soul had shrunk and died,

And left a waste within.

Con the dead page as

’twere live love: press on!

Cold wisdom’s words will ease thy track for thee;

Aye, go; cast off sweet ways, and leave me wan

To biting blasts that are intent on me.

p.

359But if thy object Fame’s far summits be,

Whose inclines many a skeleton o’erlies

That missed both dream and substance, stop and see

How absence wears these cheeks and dims these eyes!

It surely is far sweeter and more wise

To water love, than toil to leave anon

A name whose glory-gleam will but advise

Invidious minds to quench it with their own,

And over which the kindliest will but stay

A moment, musing, “He, too, had his day!”

Westbourne Park Villas,

1867.

I say, “She

was as good as fair,”

When standing by her mound;

“Such passing sweetness,” I declare,

“No longer treads the ground.”

I say, “What living Love can catch

Her bloom and bonhomie,

And what in newer maidens match

Her olden warmth to me!”

p.

361—There stands within yon vestry-nook

Where bonded lovers sign,

Her name upon a faded book

With one that is not mine.

To him she breathed the tender vow

She once had breathed to me,

But yet I say, “O love, even now

Would I had died for thee!”

You did not come,

And marching Time drew on, and wore me numb.—

Yet less for loss of your dear presence there

Than that I thus found lacking in your make

That high compassion which can overbear

Reluctance for pure lovingkindness’ sake

Grieved I, when, as the hope-hour stroked its sum,

You did not come.

p. 363You love

not me,

And love alone can lend you loyalty;

—I know and knew it. But, unto the store

Of human deeds divine in all but name,

Was it not worth a little hour or more

To add yet this: Once, you, a woman, came

To soothe a time-torn man; even though it be

You love not me?

Between us now and

here—

Two thrown together

Who are not wont to wear

Life’s flushest feather—

Who see the scenes slide past,

The daytimes dimming fast,

Let there be truth at last,

Even if despair.

p.

365So thoroughly and long

Have you now known me,

So real in faith and strong

Have I now shown me,

That nothing needs disguise

Further in any wise,

Or asks or justifies

A guarded tongue.

Face unto face, then, say,

Eyes mine own meeting,

Is your heart far away,

Or with mine beating?

When false things are brought low,

And swift things have grown slow,

Feigning like froth shall go,

Faith be for aye.

How great my grief,

my joys how few,

Since first it was my fate to know thee!

—Have the slow years not brought to view

How great my grief, my joys how few,

Nor memory shaped old times anew,

Nor loving-kindness helped to show thee

How great my grief, my joys how few,

Since first it was my fate to know thee?

I need not go

Through sleet and snow

To where I know

She waits for me;

She will wait me there

Till I find it fair,

And have time to spare

From company.

When I’ve overgot

The world somewhat,

When things cost not

Such stress and strain,

p. 368Is soon

enough

By cypress sough

To tell my Love

I am come again.

And if some day,

When none cries nay,

I still delay

To seek her side,

(Though ample measure

Of fitting leisure

Await my pleasure)

She will riot chide.

What—not upbraid me

That I delayed me,

Nor ask what stayed me

So long? Ah, no!—

New cares may claim me,

New loves inflame me,

She will not blame me,

But suffer it so.

I

For long the cruel

wish I knew

That your free heart should ache for me

While mine should bear no ache for you;

For, long—the cruel wish!—I knew

How men can feel, and craved to view

My triumph—fated not to be

For long! . . . The cruel wish I knew

That your free heart should ache for me!

At last one pays the penalty—

The woman—women always do.

My farce, I found, was tragedy

At last!—One pays the penalty

With interest when one, fancy-free,

Learns love, learns shame . . . Of sinners two

At last one pays the penalty—

The woman—women always do!

In

years defaced and lost,

Two sat here, transport-tossed,

Lit by a living love

The wilted world knew nothing of:

Scared momently

By gaingivings,

Then hoping things

That could not be.

p. 372Of love and us no trace

Abides upon the place;

The sun and shadows wheel,

Season and season sereward steal;

Foul days and fair

Here, too, prevail,

And gust and gale

As everywhere.

But lonely shepherd souls

Who bask amid these knolls

May catch a faery sound

On sleepy noontides from the ground:

“O not again

Till Earth outwears

Shall love like theirs

Suffuse this glen!”

Is it worth while, dear, now,

To call for bells, and sally forth arrayed

For marriage-rites—discussed, decried, delayed

So many

years?

Is it worth

while, dear, now,

To stir desire for old fond purposings,

By feints that Time still serves for dallyings,

Though quittance

nears?

p. 374Is it worth

while, dear, when

The day being so far spent, so low the sun,

The undone thing will soon be as the done,

And smiles as tears?

Is it worth

while, dear, when

Our cheeks are worn, our early brown is gray;

When, meet or part we, none says yea or nay,

Or heeds, or cares?

Is it worth

while, dear, since

We still can climb old Yell’ham’s wooded mounds

Together, as each season steals its rounds

And disappears?

Is it worth

while, dear, since

As mates in Mellstock churchyard we can lie,

Till the last crash of all things low and high

Shall end the spheres?

By Mellstock Lodge

and Avenue

Towards her door I went,

And sunset on her window-panes

Reflected our intent.

The creeper on the gable nigh

Was fired to more than red

And when I came to halt thereby

“Bright as my joy!” I said.

p.

376Of late days it had been her aim

To meet me in the hall;

Now at my footsteps no one came;

And no one to my call.

Again I knocked; and tardily

An inner step was heard,

And I was shown her presence then

With scarce an answering word.

She met me, and but barely took

My proffered warm embrace;

Preoccupation weighed her look,

And hardened her sweet face.

“To-morrow—could you—would

you call?

Make brief your present stay?

My child is ill—my one, my all!—

And can’t be left to-day.”

And then she turns, and gives commands

As I were out of sound,

Or were no more to her and hers

Than any neighbour round . . .

p.

377—As maid I wooed her; but one came

And coaxed her heart away,

And when in time he wedded her

I deemed her gone for aye.

He won, I lost her; and my loss

I bore I know not how;

But I do think I suffered then

Less wretchedness than now.

For Time, in taking him, had oped

An unexpected door

Of bliss for me, which grew to seem

Far surer than before . . .

Her word is steadfast, and I know

That plighted firm are we:

But she has caught new love-calls since

She smiled as maid on me!

If hours be years

the twain are blest,

For now they solace swift desire

By bonds of every bond the best,

If hours be years. The twain are blest

Do eastern stars slope never west,

Nor pallid ashes follow fire:

If hours be years the twain are blest,

For now they solace swift desire.

A dream of mine flew

over the mead

To the halls where my old Love reigns;

And it drew me on to follow its lead:

And I stood at her window-panes;

And I saw but a thing of flesh and bone

Speeding on to its cleft in the clay;

And my dream was scared, and expired on a moan,

And I whitely hastened away.

I

I saw a dead man’s finer part

Shining within each faithful heart

Of those bereft. Then said I: “This must be

His immortality.”

II

I looked there as the seasons

wore,

And still his soul continuously upbore

Its life in theirs. But less its shine excelled

Than when I first beheld.

His fellow-yearsmen passed,

and then

In later hearts I looked for him again;

And found him—shrunk, alas! into a thin

And spectral mannikin.

IV

Lastly I ask—now old

and chill—

If aught of him remain unperished still;

And find, in me alone, a feeble spark,

Dying amid the dark.

February 1899.

I

I heard a small sad sound,

And stood awhile amid the tombs around:

“Wherefore, old friends,” said I, “are ye

distrest,

Now, screened from life’s unrest?”

—“O not at being

here;

But that our future second death is drear;

When, with the living, memory of us numbs,

And blank oblivion comes!

III

“Those who our

grandsires be

Lie here embraced by deeper death than we;

Nor shape nor thought of theirs canst thou descry

With keenest backward eye.

IV

“They bide as quite

forgot;

They are as men who have existed not;

Theirs is a loss past loss of fitful breath;

It is the second death.

V

“We here, as yet, each

day

Are blest with dear recall; as yet, alway

In some soul hold a loved continuance

Of shape and voice and glance.

“But what has been will

be—

First memory, then oblivion’s turbid sea;

Like men foregone, shall we merge into those

Whose story no one knows.

VII

“For which of us could

hope

To show in life that world-awakening scope

Granted the few whose memory none lets die,

But all men magnify?

VIII

“We were but

Fortune’s sport;

Things true, things lovely, things of good report

We neither shunned nor sought . . . We see our bourne,

And seeing it we mourn.”

I

Never a careworn

wife but shows,

If a joy suffuse her,

Something beautiful to those

Patient to peruse her,

Some one charm the world unknows

Precious to a muser,

Haply what, ere years were foes,

Moved her mate to choose her.

But, be it a hint of rose

That an instant hues her,

Or some early light or pose

Wherewith thought renews her—

Seen by him at full, ere woes

Practised to abuse her—

Sparely comes it, swiftly goes,

Time again subdues her.

I

As newer comers

crowd the fore,

We drop behind.

—We who have laboured long and sore

Times out of mind,

And keen are yet, must not regret

To drop behind.

Yet there are of us some who grieve

To go behind;

Staunch, strenuous souls who scarce believe

Their fires declined,

And know none cares, remembers, spares

Who go behind.

III

’Tis not that we have unforetold

The drop behind;

We feel the new must oust the old

In every kind;

But yet we think, must we, must we,

Too, drop behind?

I

A shaded lamp and a

waving blind,

And the beat of a clock from a distant floor:

On this scene enter—winged, horned, and spined—

A longlegs, a moth, and a dumbledore;

While ’mid my page there idly stands

A sleepy fly, that rubs its hands . . .

Thus meet we five, in this still place,

At this point of time, at this point in space.

—My guests parade my new-penned ink,

Or bang at the lamp-glass, whirl, and sink.

“God’s humblest, they!” I muse. Yet

why?

They know Earth-secrets that know not I.

Max Gate, 1899.

“Men know but

little more than we,

Who count us least of things terrene,

How happy days are made to be!

“Of such strange tidings what think

ye,

O birds in brown that peck and preen?

Men know but little more than we!

p.

392“When I was borne from yonder tree

In bonds to them, I hoped to glean

How happy days are made to be,

“And want and wailing turned to glee;

Alas, despite their mighty mien

Men know but little more than we!

“They cannot change the Frost’s

decree,

They cannot keep the skies serene;

How happy days are made to be

“Eludes great Man’s sagacity

No less than ours, O tribes in treen!

Men know but little more than we

How happy days are made to be.”

Around the house the

flakes fly faster,

And all the berries now are gone

From holly and cotoneaster

Around the house. The flakes fly!—faster

Shutting indoors that crumb-outcaster

We used to see upon the lawn

Around the house. The flakes fly faster,

And all the berries now are gone!

Max Gate.

They are not those

who used to feed us

When we were young—they cannot be—

These shapes that now bereave and bleed us?

They are not those who used to feed us,—

For would they not fair terms concede us?

—If hearts can house such treachery

They are not those who used to feed us

When we were young—they cannot be!

Scene.—A wide stretch of fallow ground recently sown with wheat, and frozen to iron hardness. Three large birds walking about thereon, and wistfully eyeing the surface. Wind keen from north-east: sky a dull grey.

(TRIOLET)

Rook.—Throughout the field I find

no grain;

The cruel frost encrusts the cornland!

Starling.—Aye: patient pecking now is vain

Throughout the field, I find . . .

Rook.—No grain!

p.

396Pigeon.—Nor will be, comrade, till it

rain,

Or genial thawings loose the lorn land

Throughout the field.

Rook.—I find no grain:

The cruel frost encrusts the cornland!

Why should this

flower delay so long

To show its tremulous plumes?

Now is the time of plaintive robin-song,

When flowers are in their tombs.

Through the slow summer, when the sun

Called to each frond and whorl

That all he could for flowers was being done,

Why did it not uncurl?

p.

398It must have felt that fervid call

Although it took no heed,

Waking but now, when leaves like corpses fall,

And saps all retrocede.

Too late its beauty, lonely thing,

The season’s shine is spent,

Nothing remains for it but shivering

In tempests turbulent.

Had it a reason for delay,

Dreaming in witlessness

That for a bloom so delicately gay

Winter would stay its stress?

—I talk as if the thing were born

With sense to work its mind;

Yet it is but one mask of many worn

By the Great Face behind.

I leant upon a

coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings from broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

p.

400The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice outburst among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carollings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

p. 401That I

could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

December 1900.

I

It bends far over

Yell’ham Plain,

And we, from Yell’ham Height,

Stand and regard its fiery train,

So soon to swim from sight.

II

It will return long years hence, when

As now its strange swift shine

Will fall on Yell’ham; but not then

On that sweet form of thine.

When the hamlet

hailed a birth

Judy used to cry:

When she heard our christening mirth

She would kneel and sigh.

She was crazed, we knew, and we

Humoured her infirmity.

p.

404When the daughters and the sons

Gathered them to wed,

And we like-intending ones

Danced till dawn was red,

She would rock and mutter, “More

Comers to this stony shore!”

When old Headsman Death laid hands

On a babe or twain,

She would feast, and by her brands

Sing her songs again.

What she liked we let her do,

Judy was insane, we knew.

Through vaults of pain,

Enribbed and wrought with groins of ghastliness,

I passed, and garish spectres moved my brain

To dire distress.

And

hammerings,

And quakes, and shoots, and stifling hotness, blent

With webby waxing things and waning things

As on I went.

p.

406“Where lies the end

To this foul way?” I asked with weakening breath.

Thereon ahead I saw a door extend—

The door to death.

It loomed

more clear:

“At last!” I cried. “The all-delivering

door!”